The Hong Kong of 1997 becomes teenage wasteland for the trio at the centre of Fruit Chan’s urgent yet melancholy debut, Made in Hong Kong (香港製造). Made on a shoestring budget using cast-off film and starring then unknowns, Chan’s New Wave inflected meditation on dead end youth is imbued with the sense of endings – illness, suicide, murder, and despair dominate the lives of these young people who ought to be beginning to live but find their paths constantly blocked. The world is changing, but far from possibility the future holds only confusion and anxiety for those left hanging in constant uncertainty.

The Hong Kong of 1997 becomes teenage wasteland for the trio at the centre of Fruit Chan’s urgent yet melancholy debut, Made in Hong Kong (香港製造). Made on a shoestring budget using cast-off film and starring then unknowns, Chan’s New Wave inflected meditation on dead end youth is imbued with the sense of endings – illness, suicide, murder, and despair dominate the lives of these young people who ought to be beginning to live but find their paths constantly blocked. The world is changing, but far from possibility the future holds only confusion and anxiety for those left hanging in constant uncertainty.

Autumn Moon (Sam Lee), our narrator, is a boy fighting to become a man but too afraid to leave his adolescence behind even if he knew how. Living alone with his mother (Doris Chow Yan-Wah) after his father abandoned the family, Moon is a high school drop out with no real job who spends his time playing basketball with the neighbourhood kids and running petty errands for small scale Triad Big Brother Wing (Sang Chan). Already indulging in a hero complex, Moon is friends with and the de facto protector of a young man with learning difficulties, Sylvester (Wenders Li), who has been disowned by his birth family and is constantly picked on, beaten up, and molested by the local high schoolers. Taking Sylvester with him on a job one day, Moon runs into Mrs. Lam (Carol Lam Kit-Fong) whose debt he’s supposed to collect but when Sylvester has one of his frequent nosebleeds on seeing Mrs Lam’s beautiful daughter, Ping (Neiky Yim Hui-Chi), Mrs. Lam manages to send them packing. Nevertheless, Sylvester and Moon end up becoming friends with Ping and enjoying the last days of Hong Kong together, engaged in a maudlin exploration of teenage mortality pangs.

As Moon puts it in his voice over, everything starts to go wrong when Sylvester picks up a pair of blood stained letters in the street. They belonged to a high school girl, Susan (Amy Tam Ka-Chuen), who we later find out killed herself from the pain of first love. The spectre of Susan haunts the trio of teens left behind who remain morbidly fascinated with her fate yet also afraid and anxious. Together they pledge to investigate her death and return the letters to their rightful owners as, one assumes, Susan would have wanted. Even so, when they finally track down the recipient of the first letter, the man Susan gave her life for, he barely looks at it and tears her carefully crafted words of heartbreak into a thousand pieces, scattering them to the wind unread.

In investigating Susan’s tragic love affair, Moon and Ping begin to fall in love but Ping too already has the grim spectre of death around her. Seriously ill, Ping is at constant risk if she can’t get a kidney transplant but the list is long and she’s running out of time. Moon wants to be the hero Ping thinks he is, but he’s powerless in the face of such a faceless threat. He makes two decisions – one, to get the money to pay her debt, and two to go on the organ donor’s register so that if anything happens to him, Ping might get his kidney, struggling to do something even if it won’t really help.

Powerlessness is the force defines Moon’s life as he adopts a kind of breezy passivity to mask the fact that he has no real agency. He says he doesn’t want to join the Triads full-time because he values his independence, prefers making his own decisions, and hates taking orders but he rarely makes decisions of his own and when he does they tend not to be good ones. Moon drifts into a life of petty gangsterism partly out of a lack of other options, and partly out of laziness. Abandoned by his father and then later by his mother too, Moon’s only real source of guidance is the minor Triad boss Big Brother Wing who, unlike his mother, at least pretends to trust and respect him. Getting hold of a gun, Moon dances around like some movie vigilante drunk on power and possibility but once again fails in the hero stakes when a friend comes to him in desperate need for help but he’s so busy playing the cool dude alone in his apartment that he doesn’t even hear him over the music.

When it comes to pulling a trigger, Moon can’t do it, no matter how many times he’s visualised the moment and seen himself making the precision kill like an ice cold hitman in a stylish thriller. Moon’s illusion of his heroic righteousness crumbles. He couldn’t save his friends, has been rejected by his family, and has lost all hope for a meaningful future. As if to underline the hopelessness and fatalism of his times, Fruit Chan ends on a radio broadcast which instructs the lister to say the same thing again, only this time in Mandarin – the language of the future. Moon, Sylvester, and Ping are all cast adrift in this dying world, abandoned by parental figures and left to face their uncertain futures all alone. As a portrait of youthful alienation and despair, Made in Hong is a timeless parable in which an indifferent society eats its young, but it’s also the story of a Hong Kong Holden Caulfield standing in for his nation as they both find themselves approaching an unbreachable threshold with no bridge in sight.

Screened at Creative Visions: Hong Kong Cinema 1997 – 2017

Trailer for the 4K restoration which premiered at the Udine Far East Film Festival 2017 (English subtitles)

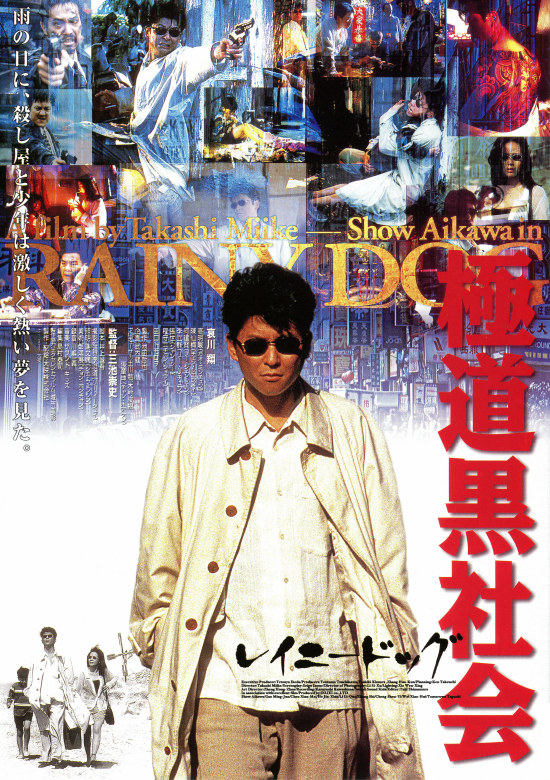

They say dogs get disorientated by the rain, all those useful smells they use to navigate the world get washed away as if someone had suddenly crumpled up their internal maps and thrown them in the waste paper bin. Yuji (Show Aikawa), the hero of Rainy Dog (極道黒社会, Gokudo Kuroshakai) – the second instalment in what is loosely thought of as Takashi Miike’s Black Society Trilogy, appears to be in a similar position as he hides out in Taipei only to find himself with no home to return to. Miike is not generally known for contemplative mood pieces, but Rainy Dog finds him feeling introspective. A noir inflected, western inspired tale of existential reckoning, this is Miike at his most melancholy but perhaps also at his most forgiving as his weary hitman lays down his burdens to open his heart only to embrace the cold steel of his destiny rather than the warmth of his redemption.

They say dogs get disorientated by the rain, all those useful smells they use to navigate the world get washed away as if someone had suddenly crumpled up their internal maps and thrown them in the waste paper bin. Yuji (Show Aikawa), the hero of Rainy Dog (極道黒社会, Gokudo Kuroshakai) – the second instalment in what is loosely thought of as Takashi Miike’s Black Society Trilogy, appears to be in a similar position as he hides out in Taipei only to find himself with no home to return to. Miike is not generally known for contemplative mood pieces, but Rainy Dog finds him feeling introspective. A noir inflected, western inspired tale of existential reckoning, this is Miike at his most melancholy but perhaps also at his most forgiving as his weary hitman lays down his burdens to open his heart only to embrace the cold steel of his destiny rather than the warmth of his redemption. Despite having started his career in the action field with the boxing film Dotsuitarunen and an entry in the New Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Junji Sakamoto has increasingly moved into gentler, socially conscious films including the Thai set Children of the Dark and the Toei 60th Anniversary prestige picture

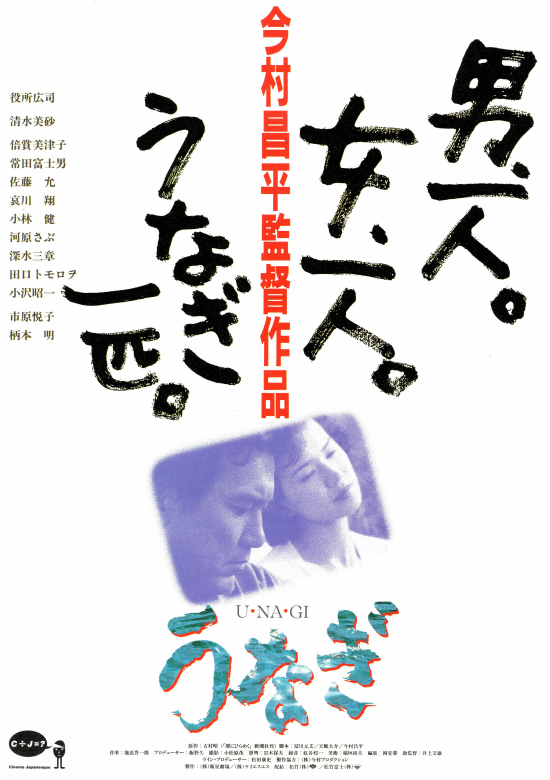

Despite having started his career in the action field with the boxing film Dotsuitarunen and an entry in the New Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Junji Sakamoto has increasingly moved into gentler, socially conscious films including the Thai set Children of the Dark and the Toei 60th Anniversary prestige picture  Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come.

Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come. Yoshitmitsu Morita tackled many different genres during his extremely varied career taking in everything from absurd social satire to teen idol vehicles and high art films. 1997’s Lost Paradise (失楽園, Shitsurakuen) again finds him in the art house realm as he prepares a tastefully erotic exploration of middle aged amour fou. Based on the bestselling novel by Junichi Watanabe, Lost Paradise also became a breakout box office hit as audiences were drawn by the tragic tale of doomed late love frustrated by societal expectations.

Yoshitmitsu Morita tackled many different genres during his extremely varied career taking in everything from absurd social satire to teen idol vehicles and high art films. 1997’s Lost Paradise (失楽園, Shitsurakuen) again finds him in the art house realm as he prepares a tastefully erotic exploration of middle aged amour fou. Based on the bestselling novel by Junichi Watanabe, Lost Paradise also became a breakout box office hit as audiences were drawn by the tragic tale of doomed late love frustrated by societal expectations. I was 21 years when I wrote this song, I’m 22 now but I won’t be for long…the leaves that are green are turning to brown for the heroine of Keiko Desu Kedo (桂子ですけど, “I am Keiko”). Approaching her 22nd birthday and with the recent death of her father ever present in her mind, she’s begun to feel the passage of time even more keenly. She doesn’t want to miss out on or forget anything so she’s going to share with us the last three weeks of her 21st year on Earth.

I was 21 years when I wrote this song, I’m 22 now but I won’t be for long…the leaves that are green are turning to brown for the heroine of Keiko Desu Kedo (桂子ですけど, “I am Keiko”). Approaching her 22nd birthday and with the recent death of her father ever present in her mind, she’s begun to feel the passage of time even more keenly. She doesn’t want to miss out on or forget anything so she’s going to share with us the last three weeks of her 21st year on Earth. Koki Mitani is one of the most bankable mainstream directors in Japan though his work has rarely travelled outside of his native land. Beginning his career in the theatre, Mitani is the master of modern comedic farce and has the rare talent of being able to ground often absurd scenarios in the humour that is very much a part of everyday life. Welcome Back, Mr. McDonald (ラヂオの時間, Radio no Jikan) is Mitani’s debut feature in the director’s chair though he previously adapted his own stage plays as screenplays for other directors. This time he sets his scene in the high pressure environment of the production booth of a live radio drama broadcast as the debut script of a shy competition winner is about to get torn to bits by egotistical actors and marred by technical hitches.

Koki Mitani is one of the most bankable mainstream directors in Japan though his work has rarely travelled outside of his native land. Beginning his career in the theatre, Mitani is the master of modern comedic farce and has the rare talent of being able to ground often absurd scenarios in the humour that is very much a part of everyday life. Welcome Back, Mr. McDonald (ラヂオの時間, Radio no Jikan) is Mitani’s debut feature in the director’s chair though he previously adapted his own stage plays as screenplays for other directors. This time he sets his scene in the high pressure environment of the production booth of a live radio drama broadcast as the debut script of a shy competition winner is about to get torn to bits by egotistical actors and marred by technical hitches.