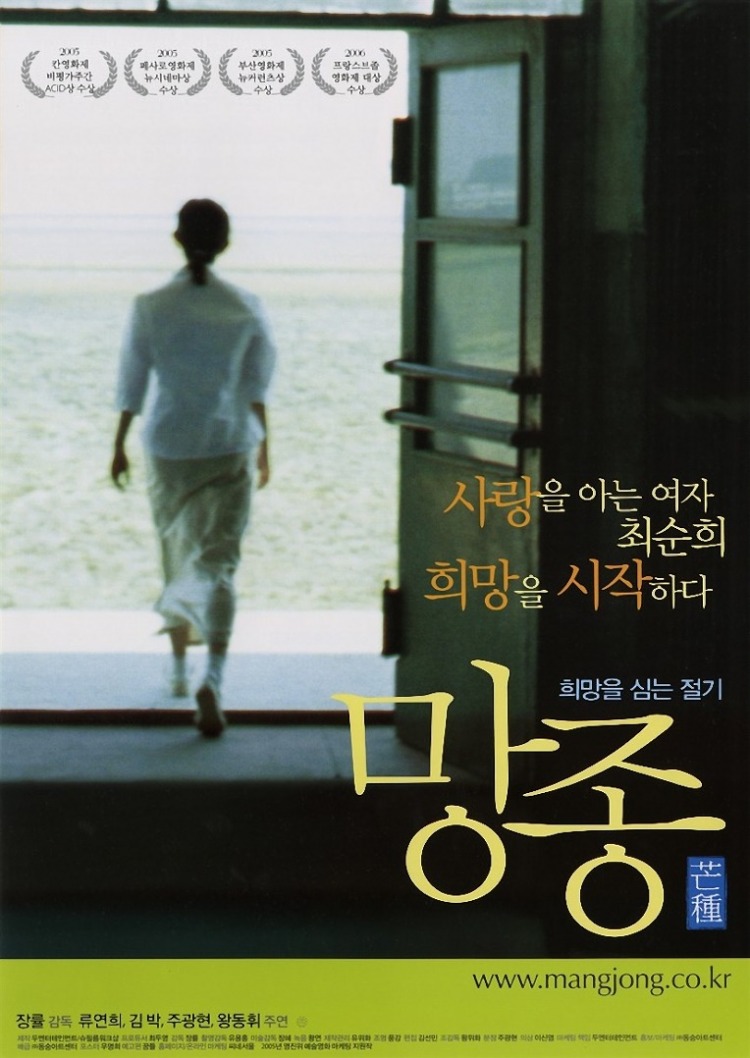

Chinese-Korean director Zhang Lu has made a career of exploring the lives of those living on the margins of modern China and most particularly those of the ethnic Korean minority. 2005’s Grain in Ear (芒种, Máng zhòng, 망종, Mang Jong) brings this theme to the fore through the struggles of its stoic heroine who bears all her troubles with quiet fortitude until the weight of her despair threatens an already fragile sense of civility, consistently eroded by multiple betrayals, misuses, and an unforgettable othering. Yet she is not entirely alone in her outsider status even if there is precious little value in solidarity among the powerless in a world of circular oppressions.

Chinese-Korean director Zhang Lu has made a career of exploring the lives of those living on the margins of modern China and most particularly those of the ethnic Korean minority. 2005’s Grain in Ear (芒种, Máng zhòng, 망종, Mang Jong) brings this theme to the fore through the struggles of its stoic heroine who bears all her troubles with quiet fortitude until the weight of her despair threatens an already fragile sense of civility, consistently eroded by multiple betrayals, misuses, and an unforgettable othering. Yet she is not entirely alone in her outsider status even if there is precious little value in solidarity among the powerless in a world of circular oppressions.

32-year-old Cui Shun-ji (Liu Lianji) has moved to a small town with her young son Chang-ho (Jin Bo) following her husband’s conviction of a violent crime. Unable to find work, she ekes out a living illegally selling kimchi from a cart without a permit while Chang-ho busies himself playing with the neighbourhood kids in the rundown industrial town. Isolated not only as a newcomer but as a member of the ethnic Korean minority, Shun-ji keeps herself to herself but can’t help attracting the attentions of the locals some of whom are merely curious about her spicy side dishes while others are intent on helping themselves to things which aren’t actually on sale.

There is something peculiarly perverse about Shun-Ji’s decision to make her living selling kimchi. It is both an act of frustrated patriotism and a kind of commodification of her ethnicity though she seems to have intense pride in her ability to produce her national dish even if there is not often as much calling for it as she would like. Meanwhile, at home, Shun-ji virtually tortures little Chang-ho into trying to learn the Korean alphabet as a way of fastening him closely to his heritage and community, but Chang-ho is a Chinese boy to all intents and purposes. He may understand Korean, but he doesn’t want or need to speak it and resents his mother’s attempts to reinforce his Koreanness.

Meanwhile, despite her aloofness, Shun-ji eventually forms a kind of relationship with a lonely Korean-Chinese man, Mr. Kim (Zhu Guangxuan), who visits her cart. Brought together by a shared sense of loneliness and a connection born only of a mutual ethnicity, the pair drift into an affair but Shun-ji’s dreams of romantic rescue will be short lived. Her lover is a weak willed man married to a feisty Chinese woman who will stop at nothing to recapture her henpecked husband. Cornered, Kim tells his wife it’s not “an affair” because money changed hands, branding Shun-ji a prostitute and getting her arrested by the police to prove his point.

To be fair, Shun-ji’s married lover is another oppressed minority afraid of the consequences of non-compliance, but he’s also just one of the terrible men that Shun-ji will encounter in her quest towards independence and self sufficiency. Her husband killed a man for money and left his family to fend for themselves when he went to prison for it. Her lover called her a whore and left her at the mercy of the police. A man who offered to help with a lucrative kimchi contract turned out to be after another kind of spice, and the kindly policeman who stopped by her cart with tales of his impending marriage turned out not to be so nice after all.

In this fiercely patriarchal world, women like Shun-ji have no one to rely upon but each other. Marginalised by poverty, ethnicity, and unfamiliarity, Shun-ji and Chang-ho live in a small shack behind the railway next to the local sex workers. Chang-ho, too small to understand why everyone calls the women next-door “chickens”, treats them all like big sisters while a kind of solidarity emerges between Shun-ji and the melancholy youngsters from far away towns who’ve travelled to this remote place to ply their trade out of desperation, too ashamed to stay any closer to home. One of the sex workers tries to warn Shun-ji about Kim – men who buy their services are not especially good romantic material, but it’s advice that falls on deaf ears. Shun-ji wants to believe better of her compatriot, but her faith is not repaid.

Zhang, in a familiar motif, foregrounds Li Bai’s famous ode to homesickness, giving it additional weight in the mouth of little Chang-ho whose longing is for another kind of home in contrast to his mother’s continued need to believe in the solidarity of her community. Yet even she eventually loses faith, tearing up Chang-ho’s Hangul cards and finally allowing him to give up on his Koreanness. Having endured so much, Shun-Li’s broken spirit eventually leads her towards an inevitable explosion and a grim, strangely poetic revenge against the society which has so badly wronged her. Only in this final moment of transgression does Shun-ji begin to harvest her own freedom, but escape is still a long way off and her final act of defiance may only further condemn her in world of constant oppressions.

Grain in Ear was screened as part of the 2018 London Korean Film Festival.

Original trailer (Mandarin and Korean with Korean subtitles only)

Walk a mile in a man’s shoes, they say, if you really want to understand him. If Kim Yong-gyun’s The Red Shoes (분홍신, Bunhongsin, 2005) is anything to go by, you’d better make sure you ask first and return them to their rightful owner afterwards without fear or covetousness. Loosely based on the classic Hans Christian Andersen tale this Korean take replaces dancing with murder and also mixes in elements from other popular Asian horror movies of the day, most notably

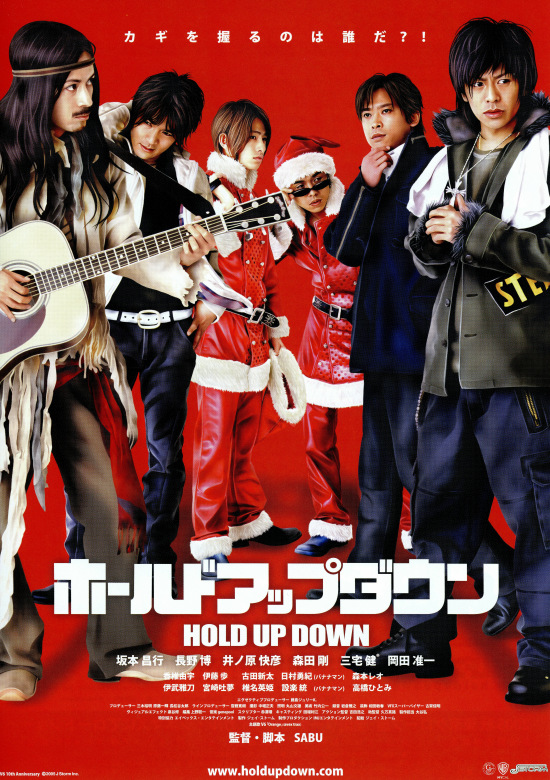

Walk a mile in a man’s shoes, they say, if you really want to understand him. If Kim Yong-gyun’s The Red Shoes (분홍신, Bunhongsin, 2005) is anything to go by, you’d better make sure you ask first and return them to their rightful owner afterwards without fear or covetousness. Loosely based on the classic Hans Christian Andersen tale this Korean take replaces dancing with murder and also mixes in elements from other popular Asian horror movies of the day, most notably  Reteaming with popular boy band V6, SABU returns with another madcap caper in the form of surreal farce Hold Up Down (ホールドアップダウン). Holding up is, as usual, not on SABU’s roadmap as he proceeds at a necessarily brisk pace, weaving these disparate plot strands into their inevitable climax. Perhaps a little shallower than the director’s other similarly themed offerings, Hold Up Down mixes everything from reverse Father Christmasing gone wrong, to gun obsessed policemen, train obsessed policewomen, clumsy defrocked priests carrying the cross of frozen Jesus, and a Shining-esque hotel filled with creepy ghosts. Quite a lot to be going on with but if SABU has proved anything it’s that he’s very adept at juggling.

Reteaming with popular boy band V6, SABU returns with another madcap caper in the form of surreal farce Hold Up Down (ホールドアップダウン). Holding up is, as usual, not on SABU’s roadmap as he proceeds at a necessarily brisk pace, weaving these disparate plot strands into their inevitable climax. Perhaps a little shallower than the director’s other similarly themed offerings, Hold Up Down mixes everything from reverse Father Christmasing gone wrong, to gun obsessed policemen, train obsessed policewomen, clumsy defrocked priests carrying the cross of frozen Jesus, and a Shining-esque hotel filled with creepy ghosts. Quite a lot to be going on with but if SABU has proved anything it’s that he’s very adept at juggling. In Japan’s rapidly ageing society, there are many older people who find themselves left alone without the safety net traditionally provided by the extended family. This problem is compounded for those who’ve lived their lives outside of the mainstream which is so deeply rooted in the “traditional” familial system. La Maison de Himiko (メゾン・ド・ヒミコ) is the name of an old people’s home with a difference – it caters exclusively to older gay men who have often become estranged from their families because of their sexuality. The proprietoress, Himiko (Min Tanaka), formerly ran an upscale gay bar in Ginza before retiring to open the home but the future of the Maison is threatened now that Himiko has contracted a terminal illness and their long term patron seems set to withdraw his support.

In Japan’s rapidly ageing society, there are many older people who find themselves left alone without the safety net traditionally provided by the extended family. This problem is compounded for those who’ve lived their lives outside of the mainstream which is so deeply rooted in the “traditional” familial system. La Maison de Himiko (メゾン・ド・ヒミコ) is the name of an old people’s home with a difference – it caters exclusively to older gay men who have often become estranged from their families because of their sexuality. The proprietoress, Himiko (Min Tanaka), formerly ran an upscale gay bar in Ginza before retiring to open the home but the future of the Maison is threatened now that Himiko has contracted a terminal illness and their long term patron seems set to withdraw his support. Kim Ki-duk is not known for his conventional approach to morality but even so his 12th feature, The Bow (활, Hwal), takes things to a whole new level of uncomfortable complexity. While nowhere near as extreme as some of Kim’s other work, The Bow takes the form of a fable as an old man and a young girl remain locked inside a mutually dependent relationship which, one way to another, is about to change forever.

Kim Ki-duk is not known for his conventional approach to morality but even so his 12th feature, The Bow (활, Hwal), takes things to a whole new level of uncomfortable complexity. While nowhere near as extreme as some of Kim’s other work, The Bow takes the form of a fable as an old man and a young girl remain locked inside a mutually dependent relationship which, one way to another, is about to change forever. Akio Jissoji has one of the most diverse filmographies of any director to date. In a career that also encompasses the landmark tokusatsu franchise Ultraman and a large selection of children’s TV, Jissoji made his mark as an avant-garde director through his three Buddhist themed art films for ATG. Summer of Ubume (姑獲鳥の夏, Ubume no Natsu) is a relatively late effort and finds Jissoji adapting a supernatural mystery novel penned by Natsuhiko Kyogoku neatly marrying most of his central concerns into one complex detective story.

Akio Jissoji has one of the most diverse filmographies of any director to date. In a career that also encompasses the landmark tokusatsu franchise Ultraman and a large selection of children’s TV, Jissoji made his mark as an avant-garde director through his three Buddhist themed art films for ATG. Summer of Ubume (姑獲鳥の夏, Ubume no Natsu) is a relatively late effort and finds Jissoji adapting a supernatural mystery novel penned by Natsuhiko Kyogoku neatly marrying most of his central concerns into one complex detective story. If you wake up one morning and decide you don’t like the world you’re living in, can you simply remake it by imagining it differently? The world of Hanging Garden (空中庭園, Kuchu Teien), based on the novel by Mitsuyo Kakuta, is a carefully constructed simulacrum – a place that is founded on total honesty yet is sustained by the willingness of its citizens to support and propagate the lies at its foundation. This is

If you wake up one morning and decide you don’t like the world you’re living in, can you simply remake it by imagining it differently? The world of Hanging Garden (空中庭園, Kuchu Teien), based on the novel by Mitsuyo Kakuta, is a carefully constructed simulacrum – a place that is founded on total honesty yet is sustained by the willingness of its citizens to support and propagate the lies at its foundation. This is  If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to live in hell, you could enjoy this fascinating promotional video which recounts events set in an isolated rural monastery somewhere in snow covered Japan. A debut feature from Tatsushi Omori (younger brother of actor Nao Omori who also plays a small part in the film), The Whispering of the Gods (ゲルマニウムの夜, Germanium no Yoru) adapted from the 1998 novel by Mangetsu Hanamura, paints an increasingly bleak picture of human nature as the lines between man and beast become hopelessly blurred in world filled with existential despair.

If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to live in hell, you could enjoy this fascinating promotional video which recounts events set in an isolated rural monastery somewhere in snow covered Japan. A debut feature from Tatsushi Omori (younger brother of actor Nao Omori who also plays a small part in the film), The Whispering of the Gods (ゲルマニウムの夜, Germanium no Yoru) adapted from the 1998 novel by Mangetsu Hanamura, paints an increasingly bleak picture of human nature as the lines between man and beast become hopelessly blurred in world filled with existential despair. SABU might have gained a reputation for his early work which often featured scenes of characters in rapid flight from one thing or another but Dead Run both embraces and rejects this aspect of his filmmaking as it presents the idea of running and its associated freedom as an unattainable dream. Based on the novel by Kiyoshi Shigematsu, Dead Run (疾走, Shisso) is the tragic story of its innocent hero, Shuji, who sees his world crumble before him only to become the sacrifice which redeems it.

SABU might have gained a reputation for his early work which often featured scenes of characters in rapid flight from one thing or another but Dead Run both embraces and rejects this aspect of his filmmaking as it presents the idea of running and its associated freedom as an unattainable dream. Based on the novel by Kiyoshi Shigematsu, Dead Run (疾走, Shisso) is the tragic story of its innocent hero, Shuji, who sees his world crumble before him only to become the sacrifice which redeems it.