Kabukicho Love Hotel (さよなら歌舞伎町, Sayonara Kabukicho), to go by its more prosaic English title, is a Runyonesque portrait of Tokyo’s red light district centered around the comings and goings of the Hotel Atlas – an establishment which rents by the hour and takes care not to ask too many questions of its clientele. The real aim of the collection of intersecting stories is more easily seen in the original Japanese title, Sayonara Kabukicho, as the vast majority of our protagonists decide to use today’s chaotic events to finally get out of this dead end town once and for all.

Kabukicho Love Hotel (さよなら歌舞伎町, Sayonara Kabukicho), to go by its more prosaic English title, is a Runyonesque portrait of Tokyo’s red light district centered around the comings and goings of the Hotel Atlas – an establishment which rents by the hour and takes care not to ask too many questions of its clientele. The real aim of the collection of intersecting stories is more easily seen in the original Japanese title, Sayonara Kabukicho, as the vast majority of our protagonists decide to use today’s chaotic events to finally get out of this dead end town once and for all.

The first couple we meet, Toru and Saya are young and apparently in love though the relationship may have all but run its course. She’s a singer-songwriter chasing her artistic dreams while he longs for a successful career in the hotel industry. He hasn’t told her that far from working at a top hotel in the city, he’s currently slumming it at the Atlas. Our next two hopefuls are a couple of (illegal) Korean migrants – she wants to open a boutique, he a restaurant. She told him she works as a hostess (which he’s not so keen on but it pays well), but she’s a high class call girl well known to the staff at the Atlas. Our third couple are a little older – Satomi works at the Atlas as a cleaner but she has a secret at home in the form of her man, Yasuo, who can’t go outside because the couple is wanted for a violent crime nearly 15 years previously. In fact, in 48hrs the statute of limitations will pass and they can finally get on with their lives but until then Satomi will continue to check the wanted posters on the way to work. That’s not to mention the tale of the teenage runaway and the hard nosed yakuza who wanted to recruit her as a call girl but had a change of heart or the porn shoot on the second floor which stars a lady with an unexpected relationship to one of the hotel’s employees…

It’s all go in Kabukicho. The punters come (ahem), go and leave barely a mark save for the odd tragedy to remind you that this is the place nobody wanted to end up. In fact, the picture Hiroki paints of Kabukicho is the oddly realistic one of someone hovering on its fringes, acknowledging the darkness of the place but refusing to meet its eyes. Everybody is, or was, dreaming of something better – Toru with his job at a five star hotel and a sparkling career in hospitality, Satomi and her romance or the Korean couple who want to make enough money to go home and start again. In short, this isn’t the place you make your life – it’s the one you fall into after you’ve hit rock bottom and promptly want to forget all about after you’ve clawed your way out.

However, while you’re there, you’re invested in the idea of it not being all that bad, really. There’s warmth and humour among the staff at the hotel who treat this pretty much the same as any other job despite its occasional messiness. In fact, the agency for the which the Korean hopeful works is run by an oddly paternalistic “pimp” (this seems far to strong a word somehow) who sits around in an apron and chats, offering comfort and fatherly advice in between dispatching various pretty young girls off to any skeevy guy who wants to rent them for an hour or two.

That’s not to say anyone is happy here though, all anyone’s focussed on is getting out and by the end the majority of them decide it’s just not worth it and the time to leave is now. Kabukicho Love Hotel may be one of Hiroki’s most mainstream efforts (despite its far less frequent than you might expect though frank sexual content) but its overlong running time and its failure to fully unify its disperate ensemble stories make it a slightly flawed one. An interestingly whimsical black comedy that takes a humorous view of Kabukicho’s darkside, Kabukicho Love Hotel is perhaps one it’s fairly easy to check out of well before the end of your stay but does offer a few of its own particular charms over the duration of your visit.

Or perhaps, you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave? We are all just prisoners here, of our own device….

Actress of the moment Sakura Ando steps into the ring, literally, for this tale of plucky underdog beating the odds in unexpected ways. It would be wrong to call 100 Yen Love (百円の恋, Hyaku Yen no Koi) a “boxing movie”, it’s more than half way through the film before the protagonist decides to embark on the surprising career herself and though there are the training sequences and match based set pieces they aren’t the focus of the film. Rather, the plucky underdog comes to the fore as we watch the virtual hikkikomori slacker Ichiko eventually become a force to be reckoned with both in the ring and out.

Actress of the moment Sakura Ando steps into the ring, literally, for this tale of plucky underdog beating the odds in unexpected ways. It would be wrong to call 100 Yen Love (百円の恋, Hyaku Yen no Koi) a “boxing movie”, it’s more than half way through the film before the protagonist decides to embark on the surprising career herself and though there are the training sequences and match based set pieces they aren’t the focus of the film. Rather, the plucky underdog comes to the fore as we watch the virtual hikkikomori slacker Ichiko eventually become a force to be reckoned with both in the ring and out. Originating as an ongoing manga series by Akiko Higashimura which was also later adapted into a popular TV anime, Princess Jellyfish adopts a slightly unusual focus as it homes in on the sometimes underrepresented female otaku.

Originating as an ongoing manga series by Akiko Higashimura which was also later adapted into a popular TV anime, Princess Jellyfish adopts a slightly unusual focus as it homes in on the sometimes underrepresented female otaku.

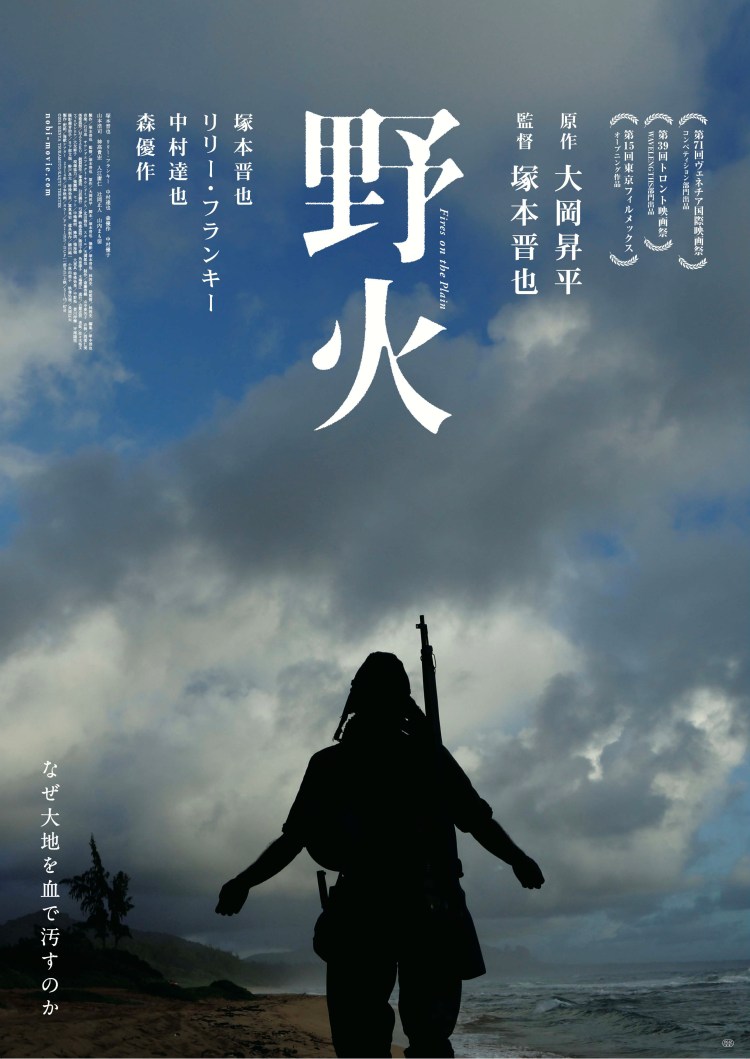

Shinya Tsukamoto is back with another characteristically visceral look at the dark sides of human nature in his latest feature length effort, Fires on the Plain (野火, Nobi). Another take on the classic, autobiographically inspired novel of the same name by Shohei Ooka (previously adapted by

Shinya Tsukamoto is back with another characteristically visceral look at the dark sides of human nature in his latest feature length effort, Fires on the Plain (野火, Nobi). Another take on the classic, autobiographically inspired novel of the same name by Shohei Ooka (previously adapted by