Growing up is a series of battles in Japan. Exam hell soon gives way to the freedom and liberation of university but students know that their carefree days of youth and discovery will be short lived. Job hunting is done en masse and takes place in the final year of study (or even before). The process of securing a work placement is much the same as deciding on which school to apply to – attending job fairs to meet with representatives, getting hold of brochures, talking to anyone and everyone you know about the various reputations of the big firms, and then figuring out what your best bets are. Many companies run written exams which are then followed by group interviews in which the applicants are made to answer humiliating questions in front of their fellow candidates. What this all amounts to is a gradual erasure of the self in order to become the perfect hire, making the same tired phrases sound interesting in an effort to say all the right things whilst trying not too seem calculating or too bland.

Growing up is a series of battles in Japan. Exam hell soon gives way to the freedom and liberation of university but students know that their carefree days of youth and discovery will be short lived. Job hunting is done en masse and takes place in the final year of study (or even before). The process of securing a work placement is much the same as deciding on which school to apply to – attending job fairs to meet with representatives, getting hold of brochures, talking to anyone and everyone you know about the various reputations of the big firms, and then figuring out what your best bets are. Many companies run written exams which are then followed by group interviews in which the applicants are made to answer humiliating questions in front of their fellow candidates. What this all amounts to is a gradual erasure of the self in order to become the perfect hire, making the same tired phrases sound interesting in an effort to say all the right things whilst trying not too seem calculating or too bland.

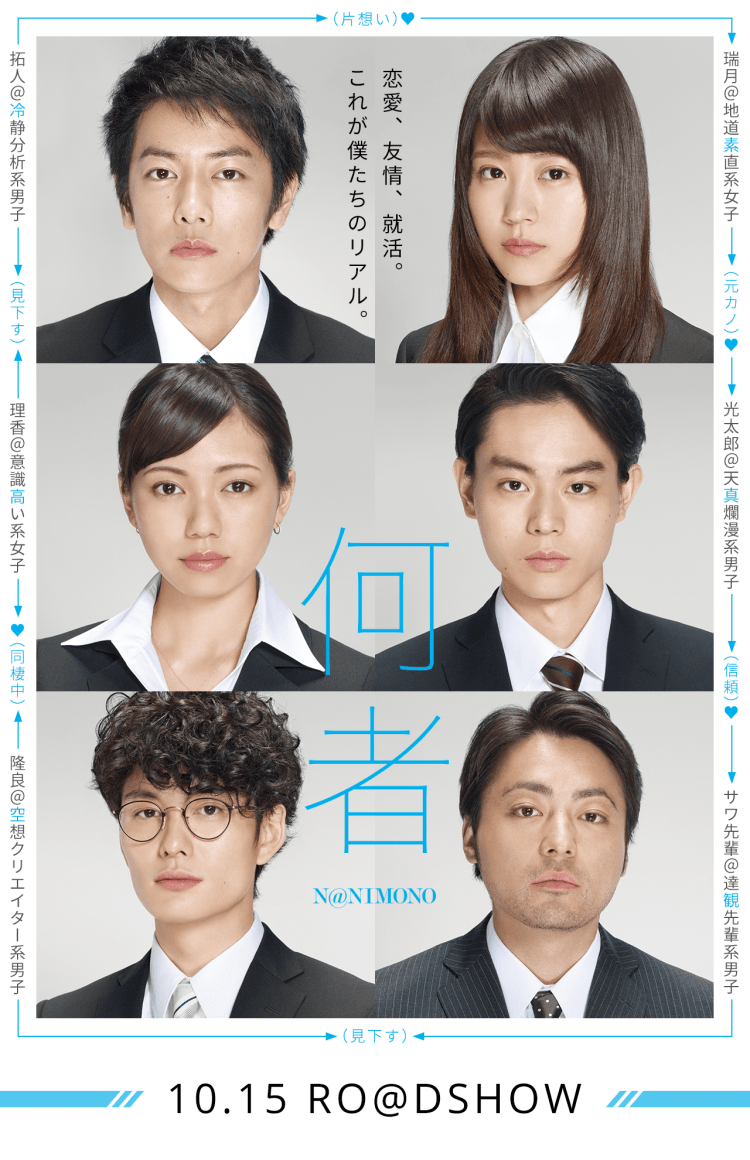

The group at the centre of Daisuke Miura’s adaptation of the Naoki Prize winning novel by Ryo Asai, N@NIMONO (何者, Nanimono, AKA Somebody / Someone), know this better than most. Protagonist Takuto (Takeru Satoh) used to be interested in theatre but has abandoned his dreams of the stage for the mainstream route into company life while his friend Kotaro (Masaki Suda) has played his last gig as the lead singer of a rock band, died his hair black again, and got a smart haircut in preparation for interviews. The boys are still good friends and roommates despite the fact that Takuto has long been carrying a torch for Kotaro’s former girlfriend, Mizuki (Kasumi Arimura), who has just returned from studying abroad. Mizuki is good friends with another girl, Rica (Fumi Nikaido), who happens to live upstairs from the boys and suggests that the four of them all get together to compare notes on the job hunting process. Rica lives with her boyfriend (still somewhat unusual in Japan), Takayoshi (Masaki Okada), who is working as a freelance journalist and is disdainful of the others’ passage into the regular workaday world but later tries to get into it himself.

There is a kind of sadness involved in this process, even if no one seriously thinks about fighting back. Everyone wants to get their foot onto that corporate ladder to become “someone”, at least in the eyes of society. There are a lot of rungs on the ladder to success, and if you miss your footing it’s near impossible to get it back – you’ll wind up one of the many crowded round the bottom staring up at the top even if you don’t want to admit it. University is the last time time there is real scope for indulging one’s personality before the corporate life takes hold – thus Takuto and Kotaro both accept that their artistic pursuits have to go in their quest for a regular middle-class life even if they inwardly struggle with their decisions to “sell-out”.

Takayoshi thinks of himself as above all this. He asks himself what all of this is for, why people put themselves through this humiliating ritual just to be locked into a nine to five that makes them miserable and turns them into soulless drones. There’s an obvious answer to that, and Takayoshi’s refusal to take it into account borders on the offensive, as does his often patronising attitude to those actively engaged in the job hunting process, but his hypocrisy is eventually brought home to him when he turns down a project to work with another artist because he thinks their work isn’t good enough. Maybe there’s courage in just putting something of yourself out there, even if it isn’t very good, rather than sitting at home looking down on everything and critiquing everyone else’s life choices whilst getting nothing done yourself.

It’s this conflict between interior and exterior life in which N@NIMONO is most interested. Main character Takuto begins as the everyman, depressed and stressed by his job hunting odyssey but aloof isolationism soon reveals itself as a kind of cowardice and self-involvement born of insecurity as he takes to a “secret” Twitter account for acerbic comments on his friends’ lives, sarcastically taking cruel potshots safe in the knowledge of his anonymity. Takuto’s entire concept of himself is a construction as his eventual descent into abstraction shows us in recasting his interaction with his friends as an avant-garde theatre show in which he finally begins to see the various ways his resentment of others is really just a way of expressing dissatisfaction with himself. This inability to fully integrate his own personality is offered as the final reason he hasn’t managed to find employment – his insincerity marks him out as a poor prospect. Takuto’s final realisation that he is unable to successfully answer the standard interview question “define your own personality in under one minute” for the perfectly sensible reason that the task is impossible kickstarts his own journey to a more complete life, even if it doesn’t do much to help the countless other “someones” out there hammered into a standard sized holes as mere cogs in the great social machine.

N@NIMONO seems to have been screened under the English titles of both “Somebody” and “Someone” but “N@NIMONO” is the one that features on the title card of the English subtitled Hong Kong blu-ray.

Original trailer (no subtitles)