Shinya Tsukamoto made his name as a punk provocateur with a series of visually arresting, experimental indie films set to a pounding industrial score and imbued with Bubble-era urban anxiety. Inspired by an Edogawa Rampo short story, 1999’s Gemini (双生児 GEMINI, Soseiji Gemini) is something of a stylistic departure from the frenetic cyberpunk energy of his earlier career, marked as much by stillness as by movement in its strikingly beautiful classical composition and intense color play. Like much of his work, however, Gemini is very much a tale of societal corruption and a man who struggles against himself, unable to resist the social codes which were handed down to him while simultaneously knowing that they are morally wrong and offend his sense of humanity.

Yukio (Masahiro Motoki) is a war hero, decorated for his service as a battlefield medic saving the life of a prominent general during the first Sino-Japanese War. He’s since come home and taken over the family business where his fame seems to have half the well-to-do residents of the area inventing spurious excuses to visit his practice, at least according to one little boy whose mum has brought him in with a bump on the head after being beset by kids from the slums. “They’re just like that from birth” Yukio later tells his wife echoing his authoritarian father, “the whole place should be burned to the ground”. A literal plague is spreading, but for Yukio the slums are a source of deadly societal corruption that presents an existential threat to his way of life, primed to infect with crime and inequity. His home, which houses his practice, is hermetically sealed from those sorts of people but lately he’s begun to feel uneasy in it. There’s a nostalgia, a sadness, a shadowy presence, not to mention a fetid stench of decay which indicates an infection has already taken place, the perimeter has been penetrated.

The shadowy presence turns out to belong to his double, Sutekichi whose name literally means “abandoned fortune”, a twin exposed at birth as unworthy of the family name owing to his imperfection in the form of a snake-like birthmark on his leg and raised by a travelling player in the slums. Having become aware of his lineage, Sutekichi has returned to make war on the old order in the form of the parents who so callously condemned him to death, engineering their demise and then pushing Yukio into a disused well with the intention of stealing his identity which comes with the added bonus that Yukio’s wife, Rin (Ryo), was once his.

Rin’s presence had already presented a point of conflict in the household, viewed with contempt and suspicion by Yukio’s mother because of her supposed amnesia brought on by a fire which destroyed her home and family. Yukio had reassured her that “you can judge a person by their clothes”, insisting that Rin is one of them, a member of the entrenched upper-middle class which finds itself in a perilous position in the society of late Meiji in which the samurai have fallen but the new order has not quite arrived. In Rin modernity has already entered the house, a slum dweller among them bringing with her not crime and disease but a freeing from traditional austerity. In opposing his parents’ will and convincing them to permit his marriage, Yukio has already signalled his motion towards the new but struggles to free himself from the oppressive thought of his father. He confesses that as a battlefield physician he doubted himself, wondering if it might not have been kinder to simply ease the suffering of those who could not be saved while his father reminds him that the German medical philosophy in which he has been trained insists that you must continue treatment to the very last.

This is the internal struggle Yukio continues to face between human compassion and the obligation to obey the accepted order which includes his father’s feelings on the inherent corruption of the slum dwellers which leads him to deny them his medical knowledge which he perhaps thinks should belong to all. The dilemma is brought home to him one night when a young woman is found violently pounding on his door wanting help for her sickly baby, but just as he makes up his mind to admit her, putting on his plague suit, a messenger arrives exclaiming that the mayor has impaled himself on something after having too much to drink. Yukio treats the mayor and tells his nurses to shoo the woman away, an action which brings him into conflict with the more compassionate Rin who cannot believe he could be so cynical or heartless.

Where Yukio is repressed kindness, a gentle soul struggling against himself, Sutekichi is passion and rage. Having taken over Yukio’s life, he takes to bed with Rin who laughs and asks him why it is he’s suddenly so amorous. She sees or thinks she sees through him, recognising Sutekichi for whose return she had been longing but also lamenting the absent Yukio who was at least soft with her in ways Sutekichi never was. “It’s a terrible world because people like you exist” Sutekichi is told by a man whose fiancée he robbed and killed. Yukio by contrast is unable to understand why this is happening to him, believing that he’s only ever tried to make people happy and has not done anything to merit being thrown in a well, failing to realise that his very position of privilege is itself oppressive, that he bears his parents’ sin in continuing to subscribe to their philosophy in insisting on their innate superiority to the slum dwellers who must be kept in their place so that they can continue to occupy theirs.

Apart, both men are opposing destructive forces in excess austerity and violent passion, only through reintegration of the self can there be a viable future. Tsukamoto casts the austerity of the medical practice in a melancholy blue, contrasting with the fiery red of the post-apocalyptic slums, eventually finding a happy medium with the house bathed in sunshine and the family seemingly repaired as a doctor in a white suit prepares to minister to the poor. Having healed himself, he begins to heal his society, treating the plague of human indifference in resistance to the prevalent anxiety of the late Meiji society.

Gemini is released on blu-ray in the UK on 2nd November courtesy of Third Window Films in a set which also includes a commentary by Tom Mes, making of featurette directed by Takashi Miike, behind the scenes, make up demonstration featurette, Venice Film Festival featurette, and original trailer.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Times change so quickly. The “danchi” was a symbol of post-war aspiration and rising economic prosperity as it sought to give young professionals an affordable yet modern, convenient way of life. The term itself is a little hard to translate though loosely enough just means a housing estate but unlike “The Projects” (団地, Danchi) of the title, these are generally not areas of social housing or lower class neighbourhoods but a kind of vertical village which one should never need to leave (except to go to work) as they also include all the necessary amenities for everyday life from shops and supermarkets to bars and restaurants. Nevertheless, aspirations change across generations and what was once considered a dreamlike promise of futuristic convenience now seems run down and squalid. Cramped apartments with tiny rooms, washing machines on the balconies, no lifts – young people do not see these things as convenient and so the danchi is mostly home to the older generation, downsizers, or the down on their luck.

Times change so quickly. The “danchi” was a symbol of post-war aspiration and rising economic prosperity as it sought to give young professionals an affordable yet modern, convenient way of life. The term itself is a little hard to translate though loosely enough just means a housing estate but unlike “The Projects” (団地, Danchi) of the title, these are generally not areas of social housing or lower class neighbourhoods but a kind of vertical village which one should never need to leave (except to go to work) as they also include all the necessary amenities for everyday life from shops and supermarkets to bars and restaurants. Nevertheless, aspirations change across generations and what was once considered a dreamlike promise of futuristic convenience now seems run down and squalid. Cramped apartments with tiny rooms, washing machines on the balconies, no lifts – young people do not see these things as convenient and so the danchi is mostly home to the older generation, downsizers, or the down on their luck. Toshiaki Toyoda has never been one for doing things in a straightforward way and so his third narrative feature sees him turning to the prison escape genre but giving it a characteristically existential twist as each of the title’s 9 Souls (ナイン・ソウルズ) search for release even outside of the literal walls of their communal cell. What begins as a quirky buddy movie about nine mismatched misfits hunting buried treasure whilst avoiding the police, ends as a melancholy character study about the fate of society’s rejected outcasts. Continuing his journey into the surreal, Toyoda’s third film is an oneiric exercise in visual poetry committed to the liberation of the form itself but also of its unlucky collection of reluctant criminals in this world or another.

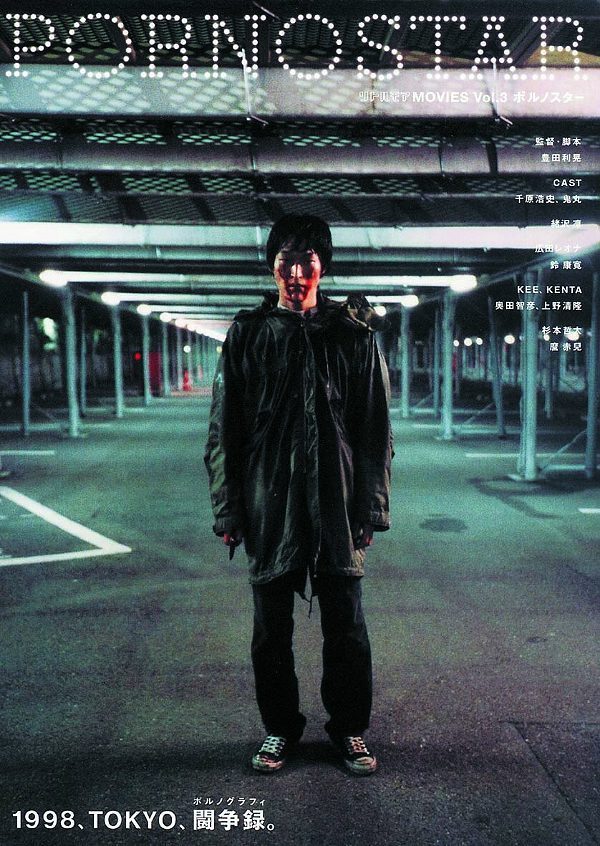

Toshiaki Toyoda has never been one for doing things in a straightforward way and so his third narrative feature sees him turning to the prison escape genre but giving it a characteristically existential twist as each of the title’s 9 Souls (ナイン・ソウルズ) search for release even outside of the literal walls of their communal cell. What begins as a quirky buddy movie about nine mismatched misfits hunting buried treasure whilst avoiding the police, ends as a melancholy character study about the fate of society’s rejected outcasts. Continuing his journey into the surreal, Toyoda’s third film is an oneiric exercise in visual poetry committed to the liberation of the form itself but also of its unlucky collection of reluctant criminals in this world or another. Looking back, at least to those of us of a certain age, the late ‘90s seem like a kind of golden era, largely free from the economic and political strife of the current world, but the cinema of that time is filled with the anxiety of the young – particularly in Japan, still mired in the wake of the post-bubble depression. Toshiaki Toyoda’s Pornostar (ポルノスター, retitled Tokyo Rampage for the US release) (not quite what it sounds like), is just such a story. Its protagonist, Arano (Chihara Junia, unnamed until the closing credits), stalks angrily through the busy city streets which remain as indifferent to him as he is to them. Though his wandering appears to have no especial purpose, Arano seethes with barely suppressed rage, nursing sharpened daggers waiting to plunge into the hearts of “unnecessary” yakuza.

Looking back, at least to those of us of a certain age, the late ‘90s seem like a kind of golden era, largely free from the economic and political strife of the current world, but the cinema of that time is filled with the anxiety of the young – particularly in Japan, still mired in the wake of the post-bubble depression. Toshiaki Toyoda’s Pornostar (ポルノスター, retitled Tokyo Rampage for the US release) (not quite what it sounds like), is just such a story. Its protagonist, Arano (Chihara Junia, unnamed until the closing credits), stalks angrily through the busy city streets which remain as indifferent to him as he is to them. Though his wandering appears to have no especial purpose, Arano seethes with barely suppressed rage, nursing sharpened daggers waiting to plunge into the hearts of “unnecessary” yakuza. Despite having started his career in the action field with the boxing film Dotsuitarunen and an entry in the New Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Junji Sakamoto has increasingly moved into gentler, socially conscious films including the Thai set Children of the Dark and the Toei 60th Anniversary prestige picture

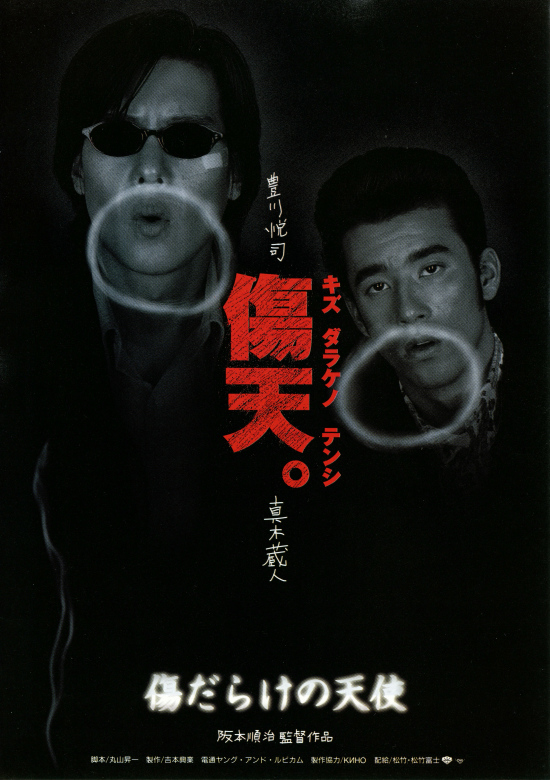

Despite having started his career in the action field with the boxing film Dotsuitarunen and an entry in the New Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Junji Sakamoto has increasingly moved into gentler, socially conscious films including the Thai set Children of the Dark and the Toei 60th Anniversary prestige picture