An oblivious housewife undergoes a kind of awakening while confronted with her husband’s transgressions by a vengeful intruder in Chan Wing-Chiu’s home invasion horror, Three Days of a Blind Girl (盲女72小時). Rendered temporarily sightless after an operation designed to save her sight, the implication is that the heroine, referred to only as Mrs Ng (Veronica Yip Yuk Hing), has been living in a fantasy of aspirational domestic success largely dependent on her heart surgeon husband Jack (Anthony Chan Yau) and devoid of her own identity while blind to the patriarchal forces which oppress her.

Having returned from surgery in the US, Mrs Ng is assured her sight will gradually return in around 72 hours though until then she will be entirely blind. The doctors give her no special instructions, and she and her husband return to their country home where they are cared for by a maid, May (Chan Yuet-Yue). Somewhat insensitively, Jack has to leave for an important heart attack conference in Macao leaving Mrs Ng solely in the custody of May only May has other plans. Her policeman boyfriend has got them concert tickets while she also needs to go out to refill her asthma medication meaning that Ms Ng will be entirely alone at home while attempting to adjust to her sightless existence.

Mrs Ng is rendered vulnerable in what should be a safe space. The sanctity of the domestic is disrupted firstly by Jack’s absence and then by an uncanny lack of familiarity introduced by her blindness. Though she has a stick, she soon finds herself bumping into things or encountering unexpected obstacles while the design of the home’s staircase appears dangerous even to the sighted and a definite health hazard to anyone else. In a moment of foreshadowing, Jack warns the maid that there’s a problem with the phone while the mobile he left is also low on battery meaning that Mrs Ng could not even call for help if she needed it.

Unsolicited help is however something she’s offered by an unexpected visitor, Sam (Anthony Wong Chau-sang), who claims to be an old school friend of Jack’s who also treated his wife for her heart condition. Mrs Ng can’t see it, but Sam is dressed in a rather unique outfit of lederhosen and a check shirt appearing something like malicious garden gnome. In an odd moment of comedy, Sam, who soon begins stalking Mrs Ng around the house, pretends to chase off an intruder by running up and down the stairs swapping characters as he goes but otherwise skews increasingly sinister while discussing his relationship with his wife who he claims has rejected him on the grounds of the printer’s ink that stains his hands.

Sam is Jack’s inversion, an overly solicitous husband now hellbent on avenging his masculinity by raping Mrs Ng to get back at Jack whom he blames for his wife’s death claiming he treated her heart condition with vitamins while abusing his position to take advantage of her sexually. At first, Mrs Ng doesn’t believe him and trusts her husband but her literal awakening occurs in line with the return of her sight. She begins to see the light and the reality of her life with Jack, ironically thanking him for this experience because it’s taught her how to fight back and protect herself in the face of his male failure. “Don’t think women are easily bullied” she claps back after finally taking charge of her life and knocking the forces of patriarchy firmly on the head.

Nevertheless, she begins to resist with regular household items such as using the serrated edge on a box of clingfilm to try and saw through the ropes binding her hands. Despite her blindness, she uses her knowledge of the domestic space against the intruder Sam and tries to frustrate his plans for her through strategy and forward thinking even while beginning to discern the danger which has always surrounded her as evidenced by the unexpected appearance of an entirely different assailant wandering in by chance in the temporary absence of Sam. “Never fight with women,” a much more confident, fully sighted, Mrs Ng later exclaims finally awakened to the realities of the world around her and unafraid to confront its ever present dangers now armed with the stylish briefcase of an independent woman. Surprisingly feminist in its overtones, Chan turns the home invasion thriller inside out as Mrs Ng mounts a successful jailbreak from the confines of a stereotypical housewife life.

Three Days of a Blind Girl screens at the Prince Charles Cinema, London on 19th October as part of Silk and Bullets: The Sisterhoods of Revenge where it will feature a video introduction by producer Alfred Cheung and pre-recorded Q&A with Director Chan Wing-Chiu.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

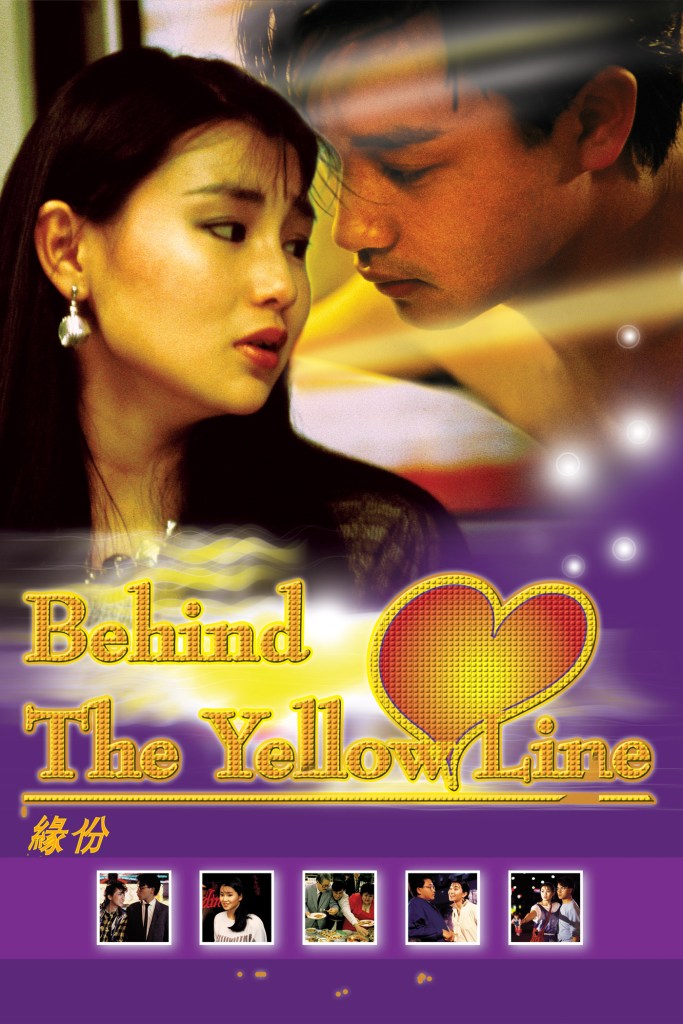

Back in the 1980s, you could make a film that’s actually no good at all but because of its fluffy, non-sensical cheesiness still manages to salvage something and capture the viewer’s good will in the process. In the intervening thirty years, this is a skill that seems to have been lost but at least we have films like Taylor Wong’s Behind the Yellow Line (緣份, Yuan Fen) to remind us this kind of disposable mainstream youth comedy was once possible. Starring three youngsters who would go on to become some of Hong Kong’s biggest stars over the next two decades, Behind the Yellow Line is no lost classic but is an enjoyable time capsule of its mid-80s setting.

Back in the 1980s, you could make a film that’s actually no good at all but because of its fluffy, non-sensical cheesiness still manages to salvage something and capture the viewer’s good will in the process. In the intervening thirty years, this is a skill that seems to have been lost but at least we have films like Taylor Wong’s Behind the Yellow Line (緣份, Yuan Fen) to remind us this kind of disposable mainstream youth comedy was once possible. Starring three youngsters who would go on to become some of Hong Kong’s biggest stars over the next two decades, Behind the Yellow Line is no lost classic but is an enjoyable time capsule of its mid-80s setting.