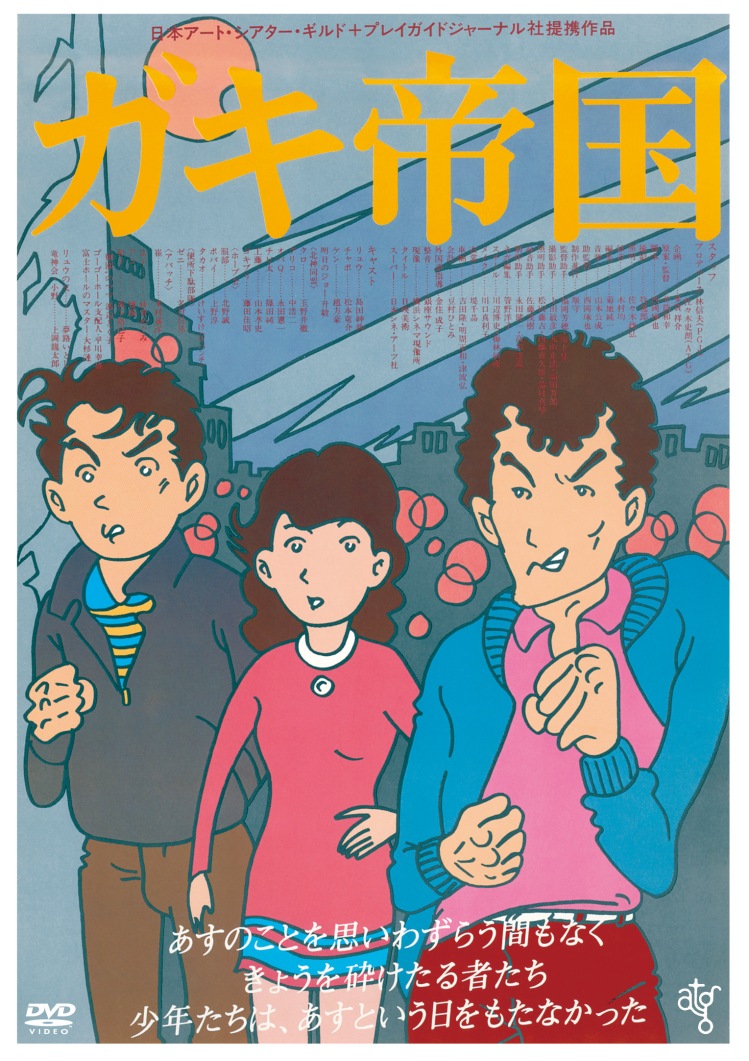

Japan in 1981 was a vastly different place than the Japan of 1967. Rising economic prosperity had produced an amiable social calm in which desire for conventional success and increasingly aspirational consumerism had replaced the firebrand need for social change which had defined the previous decade. Filmmaker, film critic, and sometimes outspoken TV personality Kazuyuki Izutsu was presumedly not a huge fan of consumerism and for this, his first “mainstream” film made for ATG, retreats back to the Osaka of 1967 in which petty street punks lamented their lack of opportunities by banding together and battling for control of their respective neighbourhoods like boys in the schoolyard only armed with knives and filled with nihilistic desperation.

Japan in 1981 was a vastly different place than the Japan of 1967. Rising economic prosperity had produced an amiable social calm in which desire for conventional success and increasingly aspirational consumerism had replaced the firebrand need for social change which had defined the previous decade. Filmmaker, film critic, and sometimes outspoken TV personality Kazuyuki Izutsu was presumedly not a huge fan of consumerism and for this, his first “mainstream” film made for ATG, retreats back to the Osaka of 1967 in which petty street punks lamented their lack of opportunities by banding together and battling for control of their respective neighbourhoods like boys in the schoolyard only armed with knives and filled with nihilistic desperation.

The film opens with our “hero”, Ryu (Shinsuke Shimada), being released from juvie after presumably getting into trouble for his petty punk antics. Waiting for him are his two best friends – soulful zainichi Korean Ken (Cho Bang-ho), and rockabilly Chabo (Ryusuke Matsumoto). Ryu is released alongside another boy, Ko (Takeshi Masu), whom he tries to recruit into their mini gang but quickly becomes an enemy, teaming up with the boys’ rivals – the Hokushin Alliance, while also becoming a potential rival for Ryu’s old girlfriend with dancing dreams, Kyoko (Megumi Sanuki). The boys, still in their last year of high school, become obsessed with trouncing their competition, proving their manhood on the streets while asserting their rightful place as the dominant forces in their native area, but as it increases in intensity the game becomes frighteningly serious and its dangers all too apparent.

Izutsu’s film fits comfortably into the “delinquent” genre but perhaps takes its cues from the Hollywood cinema of alienation more than the tough guy antics of the youth movie past. From Chabo’s bright red jacket and neatly greased quiff, the starting point is Rebel Without a Cause as these otherwise not too bad kids struggle with their place in the world, unable to see a clear path and direction for themselves in the society of 1967 which seemed both frustratingly open and closed to unremarkable lower middle-class boys. Ryu’s brother is going to give up football to go to cram school so he doesn’t end up like Ryu, while Ryu has taken to reading brain training books to try and get back on the academic path to success which he fears may have already passed him by. Ken, idly talking of the future, can’t see much beyond winding up in the yakuza, opening a bowling alley, or maybe becoming a comedian (this is Osaka after all). None of these guys is going to university or getting a salaryman job, they know not much awaits them outside of low-paid manual work, marriage, children, family and death, so they take their frustrations out on each other playing at gangsterism out on the streets.

For Ryu, Ken, and Chabo the reasons for their violence are “honourable” – they want to keep their local space local and are committed to defending it from the “external” threat of the shadier street punks from uptown. Apparently from stable economic backgrounds, the boys’ acts of street justice have no particular economic component, in contrast to those of the Hokushin Alliance which positions itself as a yakuza training school with a brutal hazing regime for new recruits and a business plan which involves hunting young women and trapping them through rape and blackmail to force them into prostitution.

Aside from lack of direction, Ken – the most introspective of the boys, also has to deal with the constant threat of discrimination due to his roots as an ethnic Korean living in Japan. One of the reasons he hates the Hokushin Alliance and distrusts some of the other gangs is that they deliberately target Koreans in racially motivated attacks. One of his old friends, Zeni (Masaaki Namura), is a member of an all Korean street gang which attempts to defend itself against the strong anti-Korean sentiment out on the streets but finds itself outgunned by the sheer weight of numbers. Ken speaks Korean openly with his friends (even when there are non-Koreans close-by) and has no interest in hiding his ethnic identity even if he uses his Japanese name in his every day life, while Ko (whom we later realise is also ethnically Korean) hides his ethnicity completely and subsumes himself into the Hokushin with a view to finally joining the yakuza even whilst knowing that the gangs he has joined are extremely prejudiced against “foreigners” and Koreans in particular. Ken would never out someone deliberately, but finds Ko’s attitude difficult to stomach, not only in his willingness to hide his roots to fit in with gangster thugs, but in his willingness to persecute his own in order to do it.

The atmosphere that surrounds the boys is one of intense futility. They fight each other pointlessly, like children in the playground, and it’s all fun and games until someone reaches for a knife. Petty disputes quickly escalate when the yakuza gets itself involved in children’s games – an assault rifle, after all, has little place in a kids’ disco where teenagers come to drink Coca Cola and slow dance to a terrible covers band singing the “uncool” music of the day. Despite the melancholy air of frustration and inevitability, Empire of Kids (ガキ帝国, Gaki Teikoku) adopts the otherwise warm and nostalgic tone of the Japanese teen movie, embracing the typically Osakan need for spiky comedy even as our guys fall ever deeper into the hole their society has cut out for them. There are few rays of sunshine to be found here, friendships are broken, trusts betrayed, and futures ruined but then again, that was only life, in Osaka, in 1967.

The family drama went through something of a transformation at the beginning of the 1980s. Gone are the picturesque, sometimes melancholy evocations of the transience of family life, these families are fake, dysfunctional, or unreliable even if trying their best. Morita’s

The family drama went through something of a transformation at the beginning of the 1980s. Gone are the picturesque, sometimes melancholy evocations of the transience of family life, these families are fake, dysfunctional, or unreliable even if trying their best. Morita’s  Yukio Mishima’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion has become one of his most representative works and seems to be one of those texts endlessly reinterpreted by each new generation. Previously adapted for the screen by Kon Ichikawa under the title of

Yukio Mishima’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion has become one of his most representative works and seems to be one of those texts endlessly reinterpreted by each new generation. Previously adapted for the screen by Kon Ichikawa under the title of  Every story is a ghost story in a sense. In every photograph there’s a presence which cannot be seen but is always felt. The filmmaker is a phantom and an enigma, but can we understand the spirit from what we see? Whose viewpoint are seeing, and can we ever separate that subjective vision from the one we create for ourselves within our own minds? The Man Who Left his Will on Film (東京戰争戦後秘話, Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa) is an oblique examination of identity but more specifically how that identity is repurposed through cinema as cinema is repurposed as a political weapon.

Every story is a ghost story in a sense. In every photograph there’s a presence which cannot be seen but is always felt. The filmmaker is a phantom and an enigma, but can we understand the spirit from what we see? Whose viewpoint are seeing, and can we ever separate that subjective vision from the one we create for ourselves within our own minds? The Man Who Left his Will on Film (東京戰争戦後秘話, Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa) is an oblique examination of identity but more specifically how that identity is repurposed through cinema as cinema is repurposed as a political weapon. Sparkling seas sound like hopeful things, especially if you’re a majestic seagull flying far above, bathed in perpetual sunshine. But then, perhaps the water below is shining with the shards of broken hopes which float on its surface, is its beauty treacherous or in earnest? So asks the singer of the title song which recurs throughout the film as if to undercut even its brief moments of happiness. There is precious little joy to be found in the lives of the two protagonists of Oh Seagull, Have You Seen the Sparkling Ocean? : An Encounter (鴎よ、きらめく海を見たか めぐり逢い, Kamome yo, Kirameku Umi wo Mitaka: Meguriai), only pain and confusion as they try to rebuild their ruined lives in an uncaring city.

Sparkling seas sound like hopeful things, especially if you’re a majestic seagull flying far above, bathed in perpetual sunshine. But then, perhaps the water below is shining with the shards of broken hopes which float on its surface, is its beauty treacherous or in earnest? So asks the singer of the title song which recurs throughout the film as if to undercut even its brief moments of happiness. There is precious little joy to be found in the lives of the two protagonists of Oh Seagull, Have You Seen the Sparkling Ocean? : An Encounter (鴎よ、きらめく海を見たか めぐり逢い, Kamome yo, Kirameku Umi wo Mitaka: Meguriai), only pain and confusion as they try to rebuild their ruined lives in an uncaring city. 1973 is the year the ninkyo eiga died. Or that is to say, staggered off into an alleyway clutching its stomach and vowing revenge whilst simultaneously seeking forgiveness from its beloved oyabun after being cruelly betrayed by the changing times! You might think it was Kinji Fukasaku who turned traitor and hammered the final nail into the coffin of Toei’s most popular genre, but Sadao Nakajima helped ram it home with the riotous explosion of proto-punk youth movie and jitsuroku-style naturalistic look at the pettiness and squalor inherent in the yakuza life – Aesthetics of a Bullet (鉄砲玉の美学, Teppodama no Bigaku). This tale of a small time loser playing the supercool big shot with no clue that he’s a sacrificial pawn in a much larger power struggle is one that has universal resonance despite the unpleasantness of its “hero”.

1973 is the year the ninkyo eiga died. Or that is to say, staggered off into an alleyway clutching its stomach and vowing revenge whilst simultaneously seeking forgiveness from its beloved oyabun after being cruelly betrayed by the changing times! You might think it was Kinji Fukasaku who turned traitor and hammered the final nail into the coffin of Toei’s most popular genre, but Sadao Nakajima helped ram it home with the riotous explosion of proto-punk youth movie and jitsuroku-style naturalistic look at the pettiness and squalor inherent in the yakuza life – Aesthetics of a Bullet (鉄砲玉の美学, Teppodama no Bigaku). This tale of a small time loser playing the supercool big shot with no clue that he’s a sacrificial pawn in a much larger power struggle is one that has universal resonance despite the unpleasantness of its “hero”. If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story

If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story