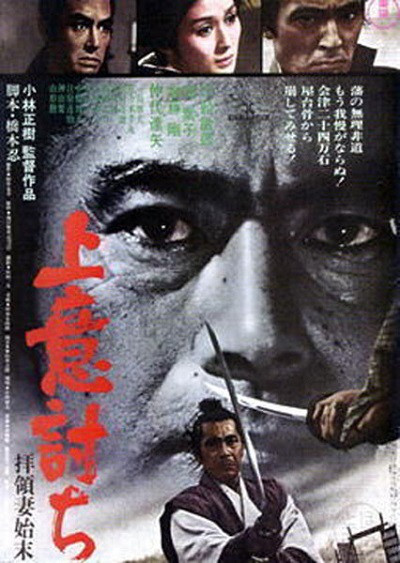

If Masaki Kobayashi had one overriding concern throughout his relatively short career, it was the place of the individual with an oppressive society. Samurai Rebellion (上意討ち 拝領妻始末, Joi-uchi: Hairyo Tsuma Shimatsu), not quite the crashing chanbara action the title promises, returns to many of the same themes presented in Kobayashi’s earlier Harakiri in its tale of corrupt lords and a vassal who can no longer submit himself to their hypocritical demands. On the film’s original release, distributor Toho added a subtitle to the otherwise stark “Rebellion”, “Hairyo Tsuma Shimatsu”, which means something like “sad story of a bestowed wife” and was intended to help boost attendance among female filmgoers who might be put off by the overly male samurai overtones. The central conflict is that of the ageing samurai Isaburo (Toshiro Mifune), but Kobayashi saves his sympathy for a powerless woman, twice betrayed, and given no means by which to defend herself in a world which values female life cheaply and a woman’s feelings not at all.

If Masaki Kobayashi had one overriding concern throughout his relatively short career, it was the place of the individual with an oppressive society. Samurai Rebellion (上意討ち 拝領妻始末, Joi-uchi: Hairyo Tsuma Shimatsu), not quite the crashing chanbara action the title promises, returns to many of the same themes presented in Kobayashi’s earlier Harakiri in its tale of corrupt lords and a vassal who can no longer submit himself to their hypocritical demands. On the film’s original release, distributor Toho added a subtitle to the otherwise stark “Rebellion”, “Hairyo Tsuma Shimatsu”, which means something like “sad story of a bestowed wife” and was intended to help boost attendance among female filmgoers who might be put off by the overly male samurai overtones. The central conflict is that of the ageing samurai Isaburo (Toshiro Mifune), but Kobayashi saves his sympathy for a powerless woman, twice betrayed, and given no means by which to defend herself in a world which values female life cheaply and a woman’s feelings not at all.

Having the misfortune to live in a time of peace, expert swordsman Isaburo has only the one duty of testing out the lord’s new sword (which he will never draw) on a straw dummy. He and his friend Tatewaki (Tatsuya Nakadai) are of a piece – two men whose skills are wasted daily and who find themselves at odds with the often cruel and arbitrary samurai world, refusing to fight each other because the outcome would only cause pain to one or both of their families. Isaburo has two grownup sons and dreams of becoming a grandpa but needs to find a wife for his eldest, Yogoro (Go Kato). He wants to find a woman who is loyal, loving, and kind. As a young man Isaburo was “forced” into marriage and adopted into his wife’s family but has been miserable ever since as his wife, Suga (Michiko Otsuka), is a sharp tongued, unpleasant woman whose only redeeming features are her stoicism and dedication to propriety.

It is then not particularly good news when the local steward turns up one day and informs Isaburo that the lord is getting rid of his mistress and has decided to marry her off to Yogoro. News travels fast and though others may appear jealous of such an “honour”, Isaburo is quietly angry – not only is he being expected to take on “damaged goods” in a woman who’s already born a son to another man, but they won’t even tell him why she’s being sent away, and the one thing he wanted for his son was not to end up in the same miserable position as he did. Nevertheless when Isaburo repeatedly tries to decline the “kind offer”, he is prevented. A suggestion quickly becomes an order, and Yogoro consents to prevent further conflict.

Against the odds, Ichi (Yoko Tsukasa) is everything Isaburo had wanted in a daughter-in-law and even puts up with Suga’s constant unkindness with patience and humility. Eventually she and Yogoro fall deeply in love and have a baby daughter, Tomi, but when the lord’s oldest heir dies and Ichi’s son becomes the next in line, it’s thought inappropriate for her to remain the wife of a mere vassal. Summoned to the castle, Ichi is once again robbed of her child but also of her happiness.

Ichi’s tale truly is a sad one and emblematic of the fates and positions of upperclass women in the feudal world. Having had the misfortune to catch the lord’s eye, Ichi tries to decline when the steward shows up to take her to the castle, reminding him that she is already betrothed. Sure that her fiancé will protect her, Ichi says she’ll go if he agrees never thinking that he would. Betrayed in love, Ichi is sold to the castle to be raped by the elderly Daimyo who views her as little more than a baby making machine and faceless body to do with as he wishes. When she returns from a post-natal trip to the spa and discovers the lord has already taken a new mistress, her anger is not born of jealously but resentment and disgust. This other woman is proud of her “position” at the lord’s side when she should be raging as Ichi is now, at her powerlessness, at the male society which reduces her to an object traded between men, and at the rapacious assault upon her body by a man older than her father.

Isaburo is also raging, but at the cruel and heartless obsession with order and protocol which has defined his short, unhappy life. Having been a model vassal, Isaburo has lived a life hemmed in by these rules but can bear them no longer in their disregard for human feeling or simple integrity. Isaburo says no, and then refuses to budge. Having retired and surrendered control of the household to Yogoro, Isaburo leaves the decision to his son who refuses to surrender his wife and swears to protect her from being subjected to the same cruel treatment as before. The samurai order is not set up for hearing the word “no”, and the actions of Isaburo, Yogoro, and Ichi threaten to bring the entire system crashing down. Love is the dangerous, destabilising, manifestation of personal desire which the system is in place to crush.

Isaburo’s rebellion, as he later says, is not for himself, or for his son and daughter-in-law whose deep love for each other has reawakened the young man in him, but for all whose personal freedom has been constrained by those who misuse their power to foster fear and oppression. Having picked up his sword, Isaburo will not stand down until his voice is heard, fairly, under these same rules that the authority is so keen on enforcing. He does not want revenge, or even to destroy the system, he just wants it to respect him and his right to refuse requests he feels are unjust or improper. Like many of Kobayashi’s heroes, Isaburo’s fate will be an unhappy one but even so he is alive again at last as the fire of rebellion rekindles his youthful heart. Those caught within the system from the venal stewards and greedy vassals to the selfish lords suddenly terrified the Shogun will discover their mass misconduct are dead men walking, sublimating their better natures in favour of creating the facade of obedience and conformity whilst manipulating those same rules for their own ends, yet the central trio, meeting their ends with defiance, are finally free.

Available with English subtitles on R1 DVD from Criterion Collection.

Original trailer (English subtitles – poor quality)

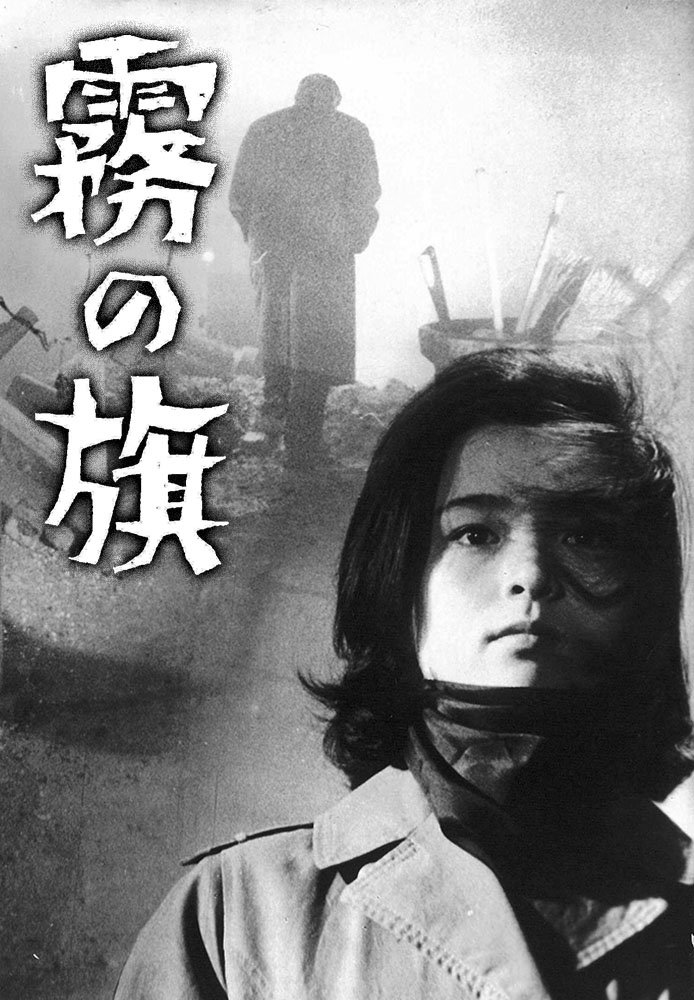

In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger.

In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger. Yukio Mishima’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion has become one of his most representative works and seems to be one of those texts endlessly reinterpreted by each new generation. Previously adapted for the screen by Kon Ichikawa under the title of

Yukio Mishima’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion has become one of his most representative works and seems to be one of those texts endlessly reinterpreted by each new generation. Previously adapted for the screen by Kon Ichikawa under the title of

Indie animation talent Makoto Shinkai has been making an impact with his beautifully drawn tales of heartbreaking, unresolvable romance for well over a decade and now with Your Name (君の名は, Kimi no Na wa) he’s finally hit the mainstream with an increased budget and distribution from major Japanese studio Toho. Noticeably more upbeat than his previous work, Your Name takes on the star-crossed lovers motif as two teenagers from different worlds come to know each other intimately without ever meeting only to find their youthful romance frustrated by the vagaries of time and fate.

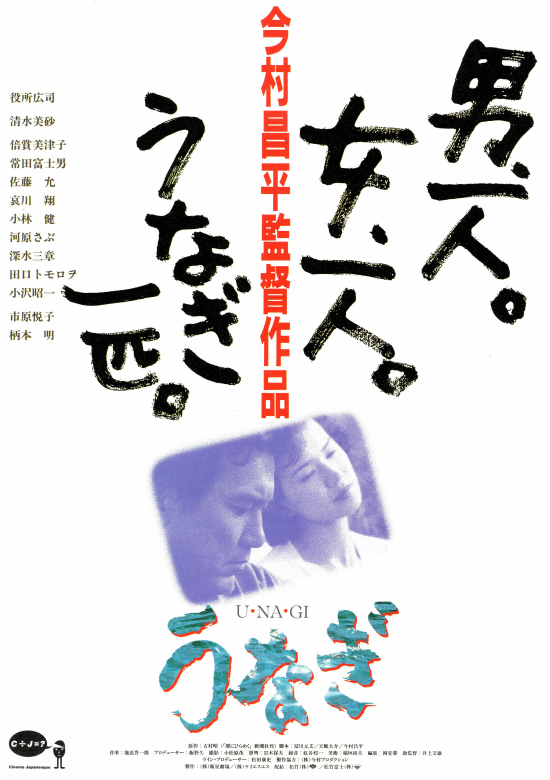

Indie animation talent Makoto Shinkai has been making an impact with his beautifully drawn tales of heartbreaking, unresolvable romance for well over a decade and now with Your Name (君の名は, Kimi no Na wa) he’s finally hit the mainstream with an increased budget and distribution from major Japanese studio Toho. Noticeably more upbeat than his previous work, Your Name takes on the star-crossed lovers motif as two teenagers from different worlds come to know each other intimately without ever meeting only to find their youthful romance frustrated by the vagaries of time and fate. Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come.

Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come.