“You’re not a bad guy after all” a previously hostile inn owner later concedes, finally seeing the method in the madness of a cynical wanderer who appears to take no side but his own but may in his own way be quietly fighting for justice in a lawless place. A samurai western set in an eerie ghost town beset by feuding gangsters whose presence has destroyed the local economy and lives of the frightened townspeople, Yojimbo (用心棒) subversively suggests that the world’s absurdity is best met with nihilistic amusement and healthy dose of irony.

When the confused hero who later gives his name as Sanjuro (Toshiro Mifune) wanders into town, he is surprised to see a stray dog running past him with a human hand in its mouth. This is indeed a dog-eat-dog society in which a petty dispute between gang members has forced the townspeople to hide behind closed doors. The streets are empty and silent until the town’s only policeman darts out and requests a “commission” for recommending Sanjuro offer his services as a bodyguard to either of the two factions suggesting that brothel owner Seibei (Seizaburo Kawazu) is on the way out and upstart Ushitora (Kyu Sazanka) is the best bet. But Sanjuro does not particularly like the look of Ushitora’s gang which as is later revealed is largely staffed by desperate disreputables, convicts, and murderers.

Sanjuro’s response is to laugh. He makes his money by killing and there are lots of people in this town the world would be better off without. He plays each side off against the other, knowing that they each need a man of his skill to break the stalemate but is rightfully mistrustful of both. First approaching Seibei, he overhears his cynical wife Orin (Isuzu Yamada) suggesting that they agree to his high fee but kill him afterwards so his services will effectively be free. Sanjuro’s plan is to antagonise both sides so they wipe each other out, freeing the town of their destructive influence. With violence so present on the streets, the townspeople are afraid to leave their homes and the only guy making any money is the undertaker.

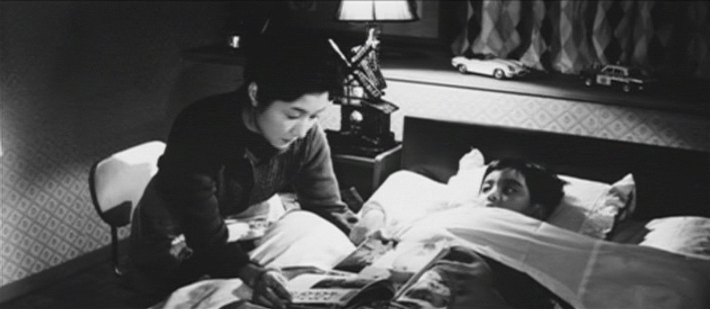

The trouble also means they can’t host the local silk fair which usually stimulates the town’s economy demonstrating the counter-productivity of the gangsters’ dispute in that no silk fair means no delegates and empty gambling rooms meaning the gangsters aren’t making any money either. Yet it’s also clear that it’s gambling that has corrupted the town and is disrupting the social order. A symptom of an economical shift, gambling offers a new path to social mobility amid the fiercely hierarchal feudal society in which the possibility of distinguishing oneself in warfare has also disappeared. Thus the young man Sanjuro encounters on the way into town argues with his father, rejecting the “long life of eating gruel” of a peasant farmer claiming he wants nice clothes and good food and has chosen to burn out brightly. Kohei (Yoshio Tsuchiya), a young father has also succumbed to the false hope offered by the gambling halls and lost everything, including his wife, to a greedy sake brewer turned silk merchant and local mayor thanks to his enthusiastic backing of Ushitora.

“I hate guys like that” Sanjuro snarls, but it seems he also hates petty gangsters and everything they represent. “This town will be quiet now” he remarks before leaving, as if stating that his work here is done and the real purpose of it was clearing out the source of the corruption rather than taking advantage of the town’s plight for his own material gain. Yojimbo quite literally means bodyguard and is the service Sanjuro offers to each side interchangeably, but Sanjuro isn’t above betraying his clients or playing one off against the other. His final foe, Ushitora’s brooding brother Unosuke (Tatsuya Nakadai), wanders around with a pistol in his kimono as if to say the age of wandering swordsmen has come to an end but in the end is exposed as complacent in his superior technology, easily neutered by Sanjuro who even gives the gun back to him as if no longer caring whether he lives or dies merely amused to find out the answer much as he had been standing on a bell tower watching the factions pointlessly tussling below. Masaru Sato’s surprisingly cheerful score seems to echo his state of mind, seeing only humour in the absurdities of the feudal order and the futility of violence while Kurosawa’s camera roves around this windswept wasteland as Sajuro kicks the gates of hell shut and prepares to move on to the next crisis in a seemingly lawless society.

Yojimbo screens at the BFI Southbank, London on 18th & 23rd February 2023 as part of the Kurosawa season.

Original trailer (English subtitles)