The hero of Masanori Tominaga’s Between the White Key and the Black Key (白鍵と黒鍵の間に, Hakken to Kokken no Aida ni) looks up and declares that it’s not Jazz if you can’t the stars, quoting Charlie Parker but mired in artistic compromise amid the heady air of Bubble-era Ginza. Adapted from the 2008 memoir of jazz pianist Hiroshi Minami, the film’s surrealist conceit sees two eras overlap confronting a jaded bandman with his naive, earnest younger self while looking for a path back towards “real” jazz.

The intentionally confusing opening sequences introduces us to Hiroshi (Sosuke Ikematsu), dressed in white, a young man with romantic jazz dreams slumming it in a moribund cabaret bar, and Minami dressed in a smooth black and wearing sunshades now the top pianist at the area’s most prestigious bar. Chaos ensues when Hiroshi, intimidated by a recently released yakuza, innocently plays his request of the Godfather Waltz without realising that the song is prohibited, only the local yakuza chairman is allowed to request it. Minami is, meanwhile, the only musician apparently allowed to play the boss’ favourite tune, but it’s a double-edged sword. He’s come to hate his life of soulless playing and feels trapped as the chairman’s favourite while secretly plotting his escape to study real jazz in America.

Irritated by the attitude of American guest singer Lisa, Minami explains that the musicians are really just decoration. At the height of the Bubble-era the bars are full of people with too much money looking to show it off. No one really cares about jazz or even about music so no one pays them any attention. Minami has long since got used to this, but is also crushed by his sense of artistic inauthenticity and declares himself sick of making music that doesn’t come from his soul.

Perhaps the rest is mere fever dream, but in the cyclical turn of events Hiroshi’s godfather faux pas comes back to haunt him, stalked by the recently released yakuza who follows him like a ghost while simultaneously dealing with the chairman’s apparent crisis which may send him abroad and change the local hierarchy forever. In the increasing surreality, the two periods overlap and influence each other as Minami is confronted by artistic compromise and forced to quite literally confront himself in a dirty alleyway while his opposite number claims that they already are in America and have been for some time.

To that extent it’s Minami who is caught between the black and white keys, looking for the sweet spot between the ability to play real jazz and the economic and social realities of his life as a Ginza bandman suffering with what he calls “bar musician disease”. His former mentor had told him that he needed to learn to play more “nonchalantly” which is advice somewhat difficult to understand but perhaps implies that Hiroshi Minami needs to learn to let himself go, to struggle less with anxiety and just play as if it were as easy as breathing. To that extent, what Minami has discovered is the wrong kind of nonchalance. Told that his job is only really to sit there and add to the false sense jazzland sophistication, he’s lost himself between the gangsters and the high rollers and is at a crossroads of an artistic crisis that maybe about to fracture his mind.

Tominaga does his best to capture an anarchic sense of a world bent out of shape and filled with surrealistic absurdity as Minami seems to see events replay with different outcomes and encounters various bizarre incidents around the back alleys of Ginza clubland themselves an incongruous mix of high class sophistication and sleaziness in which gangsters still rule the roost. Consequently the other players in Minami’s psycho drama remain largely cyphers, themselves part of the furniture in this weird mental landscape in which violence appears cartoonishly and in silence, never really connecting and irony rules in the petty gangsters who see the the Godfather Waltz as their song. In any case, Minami seems to recover himself, partly thanks to a vision of his oblivious mother retuning to him something that was lost, in the simple act of sitting down to play as if it were the beginning once again, or perhaps it really is, more acquainted with the music of his soul.

Between the White Key and the Black Key screens in New York July 10 as the opening night of this year’s JAPAN CUTS.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

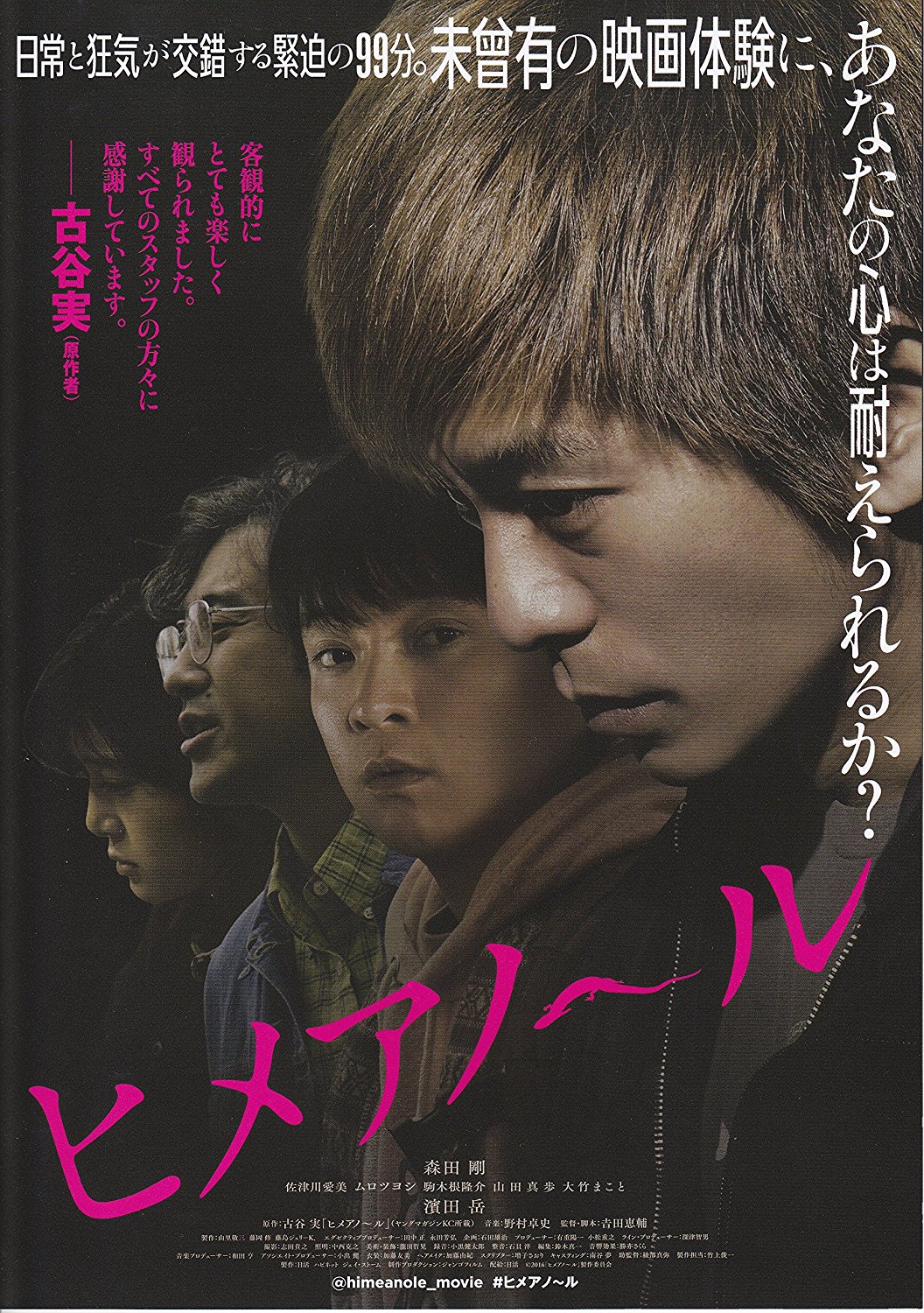

Some people are odd, and that’s OK. Then there are the people who are odd, but definitely not OK. Hime-anole (ヒメアノ~ル) introduces us to both of these kinds of outsiders, attempting to draw a line between the merely awkward and the actively dangerous but ultimately finding that there is no line and perhaps simple acts of kindness offered at the right time could have prevented a mind snapping or a person descending into spiralling homicidal delusion. To go any further is to say too much, but Hime-anole revels in its reversals, switching rapidly between quirky romantic comedy, gritty Japanese indie, and finally grim social horror. Yet it plants its seeds early with two young men struggling to express their true emotions, trapped and lonely, leading unfulfilling lives. Their dissatisfaction is ordinary, but these same repressed emotions taken to an extreme can produce much more harmful results than two guys eating stale donuts everyday just to ask a pretty girl for the bill.

Some people are odd, and that’s OK. Then there are the people who are odd, but definitely not OK. Hime-anole (ヒメアノ~ル) introduces us to both of these kinds of outsiders, attempting to draw a line between the merely awkward and the actively dangerous but ultimately finding that there is no line and perhaps simple acts of kindness offered at the right time could have prevented a mind snapping or a person descending into spiralling homicidal delusion. To go any further is to say too much, but Hime-anole revels in its reversals, switching rapidly between quirky romantic comedy, gritty Japanese indie, and finally grim social horror. Yet it plants its seeds early with two young men struggling to express their true emotions, trapped and lonely, leading unfulfilling lives. Their dissatisfaction is ordinary, but these same repressed emotions taken to an extreme can produce much more harmful results than two guys eating stale donuts everyday just to ask a pretty girl for the bill. Reteaming with popular boy band V6, SABU returns with another madcap caper in the form of surreal farce Hold Up Down (ホールドアップダウン). Holding up is, as usual, not on SABU’s roadmap as he proceeds at a necessarily brisk pace, weaving these disparate plot strands into their inevitable climax. Perhaps a little shallower than the director’s other similarly themed offerings, Hold Up Down mixes everything from reverse Father Christmasing gone wrong, to gun obsessed policemen, train obsessed policewomen, clumsy defrocked priests carrying the cross of frozen Jesus, and a Shining-esque hotel filled with creepy ghosts. Quite a lot to be going on with but if SABU has proved anything it’s that he’s very adept at juggling.

Reteaming with popular boy band V6, SABU returns with another madcap caper in the form of surreal farce Hold Up Down (ホールドアップダウン). Holding up is, as usual, not on SABU’s roadmap as he proceeds at a necessarily brisk pace, weaving these disparate plot strands into their inevitable climax. Perhaps a little shallower than the director’s other similarly themed offerings, Hold Up Down mixes everything from reverse Father Christmasing gone wrong, to gun obsessed policemen, train obsessed policewomen, clumsy defrocked priests carrying the cross of frozen Jesus, and a Shining-esque hotel filled with creepy ghosts. Quite a lot to be going on with but if SABU has proved anything it’s that he’s very adept at juggling. The Fallen Angel (人間失格, Ningen Shikkaku), based on one of the best known works of Japanese literary giant Osamu Dazai – No Longer Human, was the last in a series of commemorative film projects marking the 100th anniversary of the author’s birth in 2009. Like much of Dazai’s work, No Longer Human is semi-autobiographical, fixated on the idea of suicide, and charts the course of its protagonist as he becomes hopelessly lost in a life of dissipation, alcohol, drugs, and overwhelming depression.

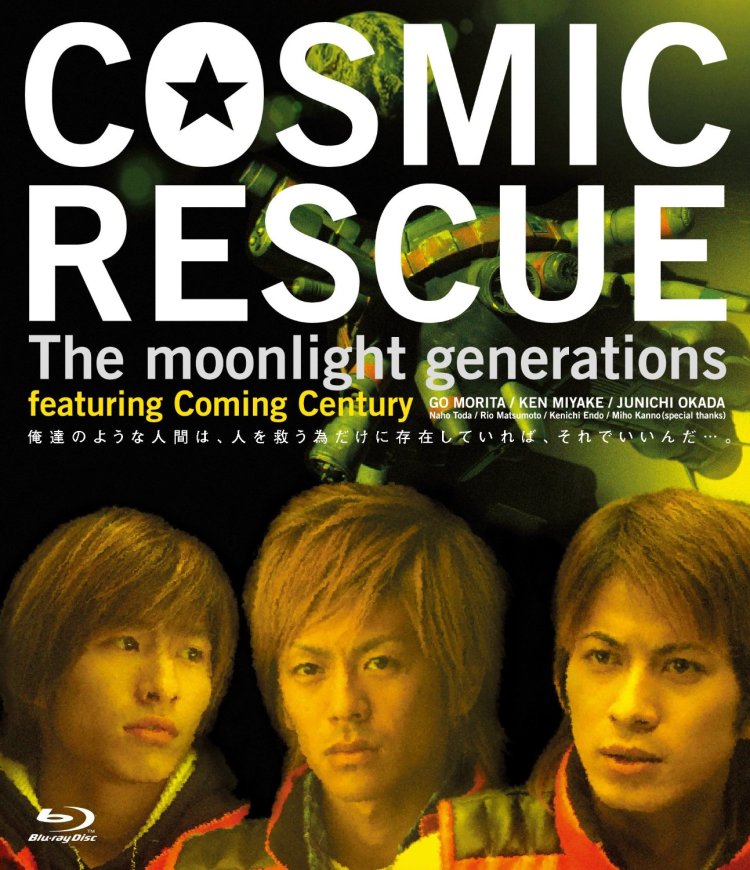

The Fallen Angel (人間失格, Ningen Shikkaku), based on one of the best known works of Japanese literary giant Osamu Dazai – No Longer Human, was the last in a series of commemorative film projects marking the 100th anniversary of the author’s birth in 2009. Like much of Dazai’s work, No Longer Human is semi-autobiographical, fixated on the idea of suicide, and charts the course of its protagonist as he becomes hopelessly lost in a life of dissipation, alcohol, drugs, and overwhelming depression. It’s often posited that Japan rarely produces “science fiction” literature or movies and some say that’s because, well, they already live there. However, this isn’t quite true, there are just as many science fiction themed projects to be found in Japan as elsewhere you just have to look a little harder to find them. Depending on your point view, if you succeed in tracking down a copy of Cosmic Rescue -The moonlight generations- (コスミック・レスキュー ザ・ムーンライト・ジェネレーションズ), you may feel the quest was not entirely worth the effort.

It’s often posited that Japan rarely produces “science fiction” literature or movies and some say that’s because, well, they already live there. However, this isn’t quite true, there are just as many science fiction themed projects to be found in Japan as elsewhere you just have to look a little harder to find them. Depending on your point view, if you succeed in tracking down a copy of Cosmic Rescue -The moonlight generations- (コスミック・レスキュー ザ・ムーンライト・ジェネレーションズ), you may feel the quest was not entirely worth the effort.