An old-school yakuza finds himself cornered on every side while caught in the confusion of Okinawa’s reversion to Japan in Sadao Nakajima’s jitsuroku gangster movie Terror of the Yakuza (沖縄やくざ戦争, Okinawa Yakuza Senso, AKA Okinawa Yakuza War). Where similarly themed Okinawa-set gangster pictures such as Sympathy for the Underdog had largely presented the islands as an appealing place for mainland gangsters because the conditions of the occupation which had allowed them to prosper were still in place, Sadao reframes the debate in terms colonisation and conquest as the hero finds himself increasingly marginalised as an island boy contending with amoral city elitists.

Nakazato (Hiroki Matsukata) has just been released from prison after serving seven years for the murders of two rival gang bosses that allowed his boss, Kunigami (Shinichi Chiba), to rule the roost in Koza. But now that Okinawa has reverted to Japan, everything has changed. Kunigami has formed a loose alliance with another regional gang to oppose the incursion of mainland yakuza but behind the scenes the higher-ups are intent on a mutually beneficial alliance with the Japanese perhaps seeing the writing on the wall and assuming that it’s better to work with the new regime that against it. For his part, Nakazato is more loyal to the clan than he is opposed to Japan but he’s also resentful towards to Kunigami for failing to live up to his side of the bargain now that he’s been released while fearing the influence of his new sidekick Ishikawa (Takeo Chii) whom he suspects of murdering one of his former associates while he was inside.

As such, much of the drama unfolds as in any other yakuza picture with Nakazato, regarded by some of the other bosses as a loose cannon and potential liability, reluctant to move against Kunigami for reasons of loyalty even while Kunigami becomes increasing unhinged and dangerous, deliberately running over an Osakan foot soldier who was apparently just on holiday with no particular business in town. Kunigami’s recklessness in his hatred of the Japanese threatens to start a turf war the Okinawan gangs fear they couldn’t win, sending snivelling yakuza middleman Onaga (Mikio Narita) along with Nakazato to negotiate in Osaka only to be told the price of peace is Kunigami’s head. Inspired by the Fourth Okinawa War which was still going on at the time of the film’s completion (in fact, the release was blocked in Okinawa in fear that it would prove simply too incendiary), the conflict takes on political overtones as the mainland gangsters assume their conquest of Okinawa is a fait accompli while those like Onaga are only too quick to capitulate leaving Kunigami and Nakazato as two very different examples of resistance.

Yet Nakazato finds himself doubly marginalised because he is from one of the smaller islands with most of his men also hailing from smaller rural communities (one uncomfortably wearing extensive makeup to ram the point home that he is from the southern reaches) with the result that they are often pushed around by the city gangsters who view them as idiot country bumpkins. On his trip to Osaka, Nakazato even describes himself as such in an attempt to curry favour apologising in advance should he make a mistake with proper gangster etiquette. Like a good platoon leader, Nakazato’s primary responsibilities are to his men which is one reason why he takes so strongly against Ishikawa, one of the new breed of entirely amoral yakuza who care nothing at all for the code and think nothing of knocking off his guys for no reason. Consequently he finds himself caught between the invading mainlanders, the unhinged chaos of Kunigami, the coldhearted greed of Ishikawa, and the spineless venality of turncoats like Onaga.

It’s no wonder that he eventually loses his cool, going all out war and like Kunigami dressing in vests and combats in an internecine quest for vengeance precipitated in part by Kunigami’s attempt to discipline one of his men for encroaching on his territory by removing his manhood with a pair of pliers. “Someone will get to you someday too” Nakazato is reminded though having lost everything including his loyal wife who insisted on selling herself to a brothel to get the money to fund his war of revenge he may no longer care so long as he cleans house in Okinawa to the extent that he is really able to do so. “Okinawa is such a scary place” one of the Japanese guys admits, though showing no signs of backing off in this maddeningly chaotic world which turns stoic veterans and hotheaded farm boys alike into enraged killers fighting on a point of principle in a world which no longer has any.

Terror of Yakuza screens at Japan Society New York May 20 at 7pm as part of Visions of Okinawa: Cinematic Reflections.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

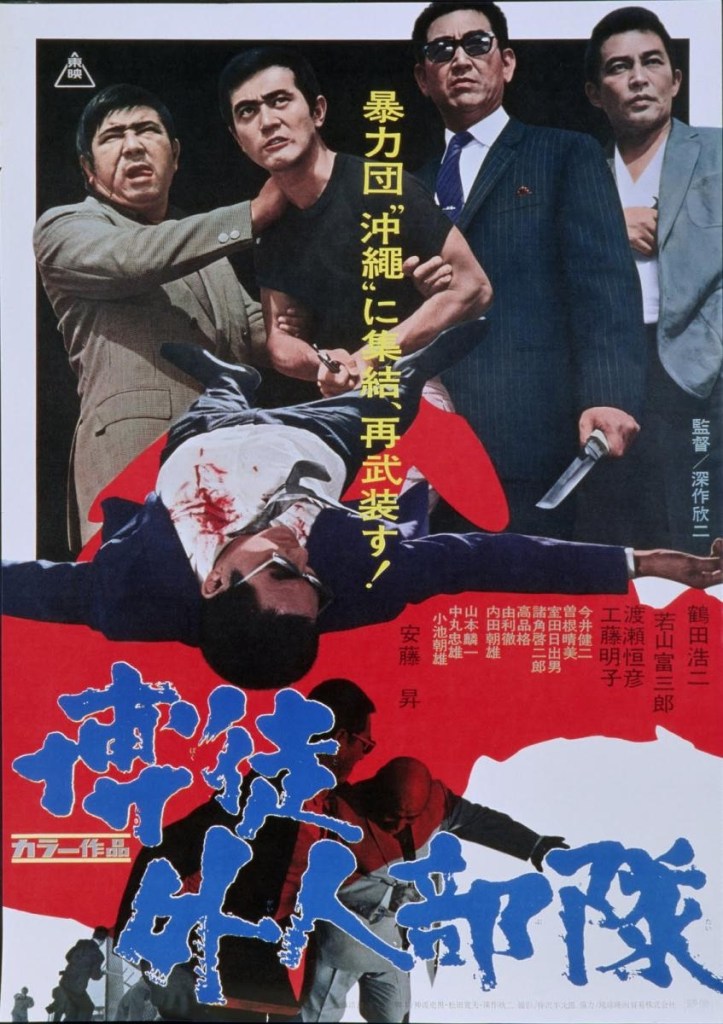

Images: Terror of Yakuza © 1976 Toei

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first  Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again.

Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again. And so, the saga finally reaches its conclusion. Final Episode (仁義なき戦い: 完結篇, Jingi Naki Tatakai: Kanketsu-hen) brings us ever closer to the contemporary era and picks up in the mid ‘60s where Hirono is still in prison and Takeda, released on a technicality, has decided to move the yakuza into the legit arena. The surviving gangs have united and rebranded themselves as a political group known as the Tensei Coalition. However, not everyone has joined the new gangsters’ union and the enterprise is fragile at best.

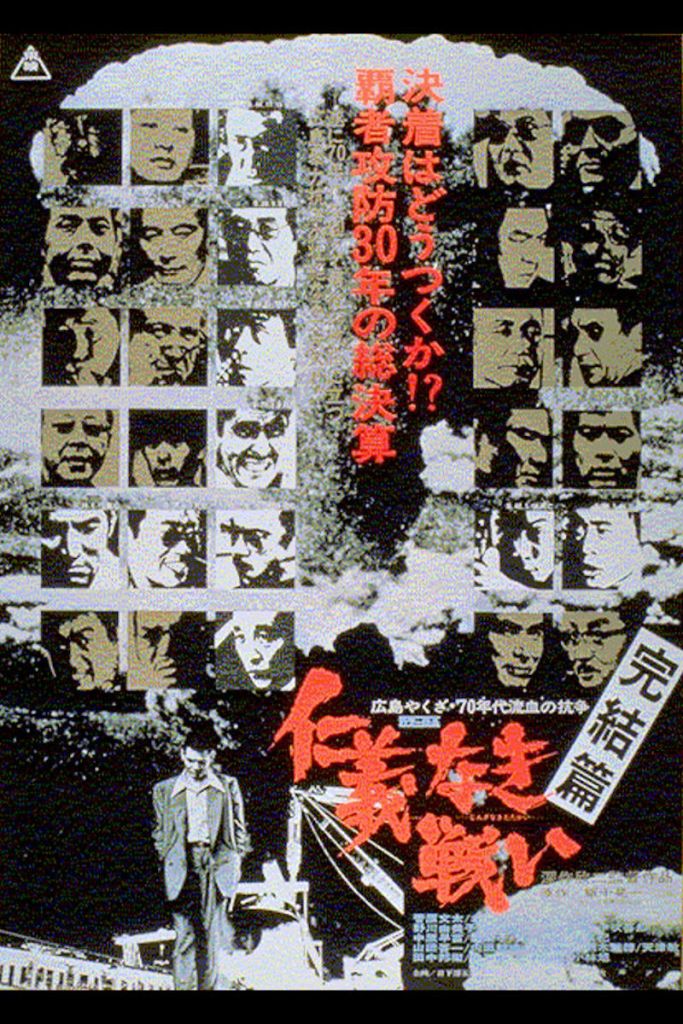

And so, the saga finally reaches its conclusion. Final Episode (仁義なき戦い: 完結篇, Jingi Naki Tatakai: Kanketsu-hen) brings us ever closer to the contemporary era and picks up in the mid ‘60s where Hirono is still in prison and Takeda, released on a technicality, has decided to move the yakuza into the legit arena. The surviving gangs have united and rebranded themselves as a political group known as the Tensei Coalition. However, not everyone has joined the new gangsters’ union and the enterprise is fragile at best. It’s 1963 now and the chaos in the yakuza world is only increasing. However, with the Tokyo olympics only a year away and the economic conditions considerably improved the outlaw life is much less justifiable. The public are becoming increasingly intolerant of yakuza violence and the government is keen to clean up their image before the tourists arrive and so the police finally decide to do something about the organised crime problem. This is bad news for Hirono and his guys who are already still in the middle of their own yakuza style cold war.

It’s 1963 now and the chaos in the yakuza world is only increasing. However, with the Tokyo olympics only a year away and the economic conditions considerably improved the outlaw life is much less justifiable. The public are becoming increasingly intolerant of yakuza violence and the government is keen to clean up their image before the tourists arrive and so the police finally decide to do something about the organised crime problem. This is bad news for Hirono and his guys who are already still in the middle of their own yakuza style cold war.