Takahiro Miki has made something of a name for himself with a particular brand of bittersweet youthful romance often featuring a fantastical element such in Girl in the Sunny Place, or My Tomorrow, Your Yesterday. Adapted from a novel by Robert A. Heinlein, The Door Into Summer (夏への扉 ―キミのいる未来へ―, Natsu e no Tobira: Kimi on iru Mirai e) is in many ways more of the same, repurposing a sci-fi-inflected, slightly uncomfortable love story as an inspirational tale of never giving up and learning to overcome personal trauma in order to seek true happiness.

In 1995, 27-year-old Soichiro (Kento Yamazaki) has experienced a lot of loss in his life. His mother passed away soon after he was born, followed by his father when he was 17. He was then taken in by a family friend and became a big brother to then 7-year-old Riko (Kaya Kiyohara), but his adoptive parents then died in a plane crash. While Riko went to live with her uncle Kazuto, Soichiro became a robotics prodigy with an internalised sense of despair that prevents him making lasting connections, believing that his fate is always to lose everything he loves. His prophecy is in a sense fulfilled when he’s duped into signing away some of his shares in the robotics company founded by his adoptive father by an unscrupulous colleague. Filled with despair, he decides to enter a cryostasis programme for 30 years intending to transfer his remaining stocks to Riko, in part avoiding the inappropriate crush she has on him and hoping to escape from reality along with his best friend/cat Pete to start again in another time when the programme promises his investments will have matured leaving him with a good quality of life. Before he can do that, however, an attempt to confront his wrongdoers backfires when he’s placed into their proprietary cryosleep programme to ensure he’s out of the way for the next three decades.

To that extent, you’d have to wonder why they’d bother rather than just getting rid of him for good. In any case, when he wakes up he realises that the shady company that housed him, Mannix, went bust years ago leaving him with no savings and also no cat because his enemy didn’t give much thought to poor Pete. In the future, however, he gets a fancy new rogue robot companion, also called PETE, who supports him as he tries to adjust to the digital world his inventions helped create before realising that he must have at some point time travelled back to 1995 to put things “right” (to a certain extent) so that could happen and starting in on that. This accidental paradox is never really addressed, Soichiro travelling to the past because he knows he already has, but not giving himself very much time to complete the magic plasma battery that powers the future while remaining in hiding until ready to disrupt his tormentors’ dastardly plan, rescue his beloved cat Pete, save Riko, and return to the future to make sure that nothing else changes in the new 2025.

It is indeed Pete that inspires the film’s title in his revulsion of winter weather, always insisting on checking all the internal doorways in the hope that one magically leads to summer which is a roundabout metaphor for film’s secondary message in the insistence on perseverance, never giving up or losing hope in a brighter future even it seems impossible. Nevertheless, it can’t be denied that there’s something slightly uncomfortable in the relationship between 27-year-old Soichiro and his 17-year-old adoptive sister Riko even as he repeatedly reminds her she’s still a child and should live her life with people her own age, especially given the implications of the romantic resolution which attempts to smooth over this awkwardness by placing them on a more equal footing if somewhat artificially. In the end, however, the most important tool for saving the future turns out to be companionship and unconditional support of the kind that Pete offered the orphaned Soichiro, a quality he later programs in to his over-curious robot “son”, PETE. Miki doesn’t do much with the hard sci-fi trappings of the original novel, but does in his best tradition craft an innocent romance as the hero learns to look for his eternal summer in the present rather than the past while overcoming his internalised despair in his cursed fate to embrace love and happiness.

Trailer (no subtitles)

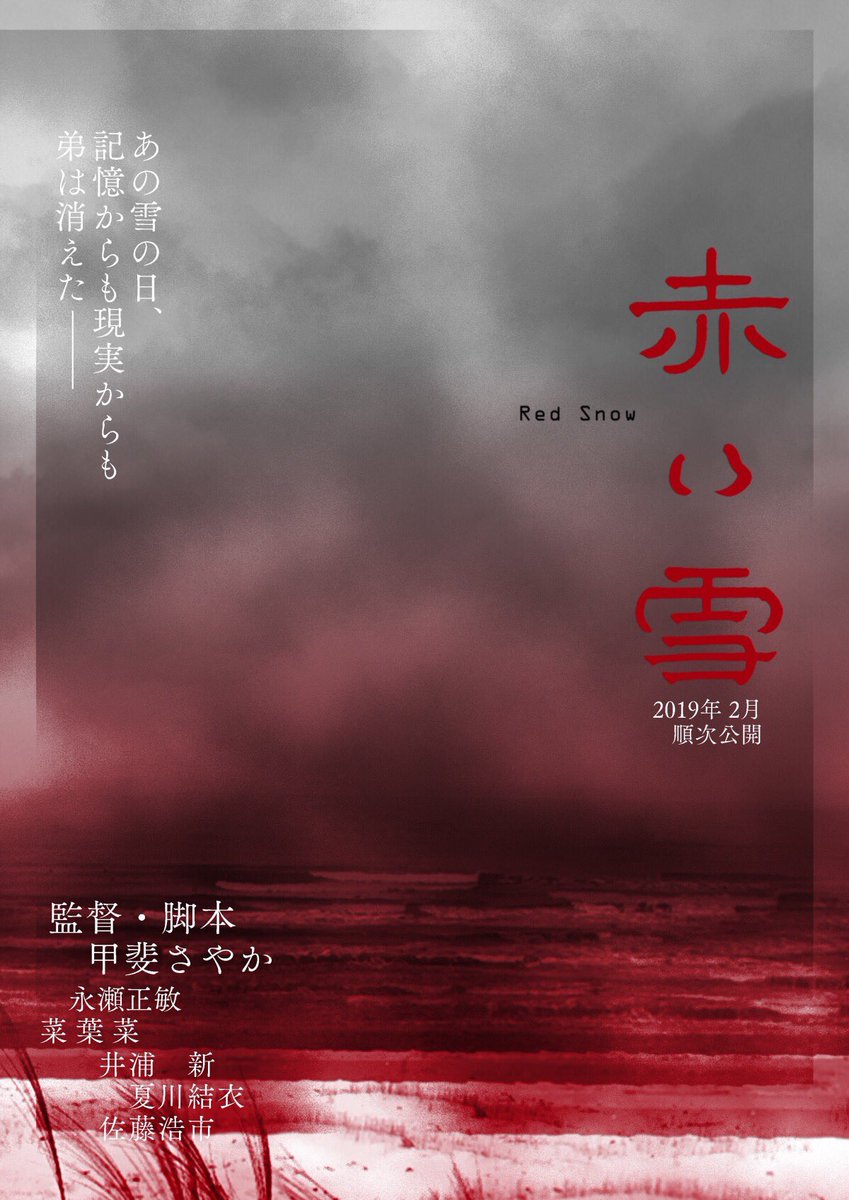

“We’re just pieces of a puzzle” a temporarily deranged woman exclaims to a gloomy seeker after truth in Sayaka Kai’s eerie debut Red Snow (赤い雪, Akai Yuki). Truth, as it turns out is an elusive concept for these variously troubled souls trapped in a purgatorial tailspin on their gloomy island home. When a stranger comes to town intent on unearthing the long buried past, he stirs up deeply repressed emotion and barely concealed anger but finds himself floundering in the maddening snows of a possibly imaginary coastal village.

“We’re just pieces of a puzzle” a temporarily deranged woman exclaims to a gloomy seeker after truth in Sayaka Kai’s eerie debut Red Snow (赤い雪, Akai Yuki). Truth, as it turns out is an elusive concept for these variously troubled souls trapped in a purgatorial tailspin on their gloomy island home. When a stranger comes to town intent on unearthing the long buried past, he stirs up deeply repressed emotion and barely concealed anger but finds himself floundering in the maddening snows of a possibly imaginary coastal village.

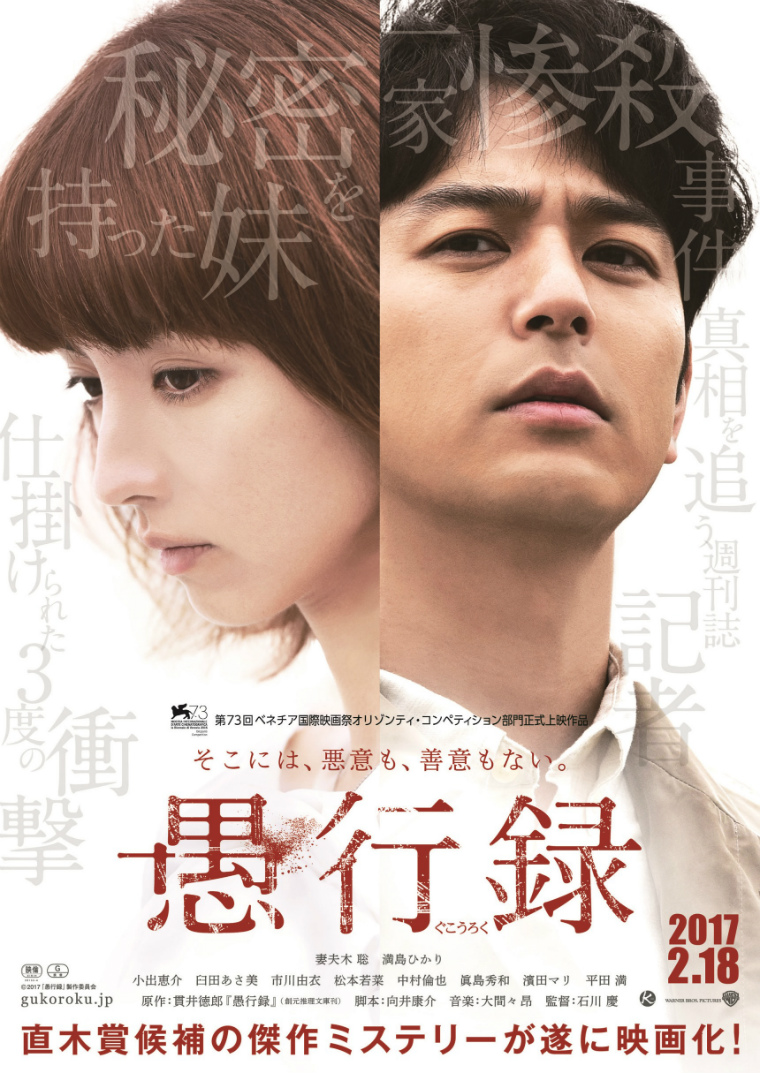

Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society.

Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society. There are two kinds of people in the world, those who swing and those who…don’t – a metaphor which works just as well for baseball and, by implication, facing life’s challenges as it does for music. Shinobu Yaguchi returns after 2001’s

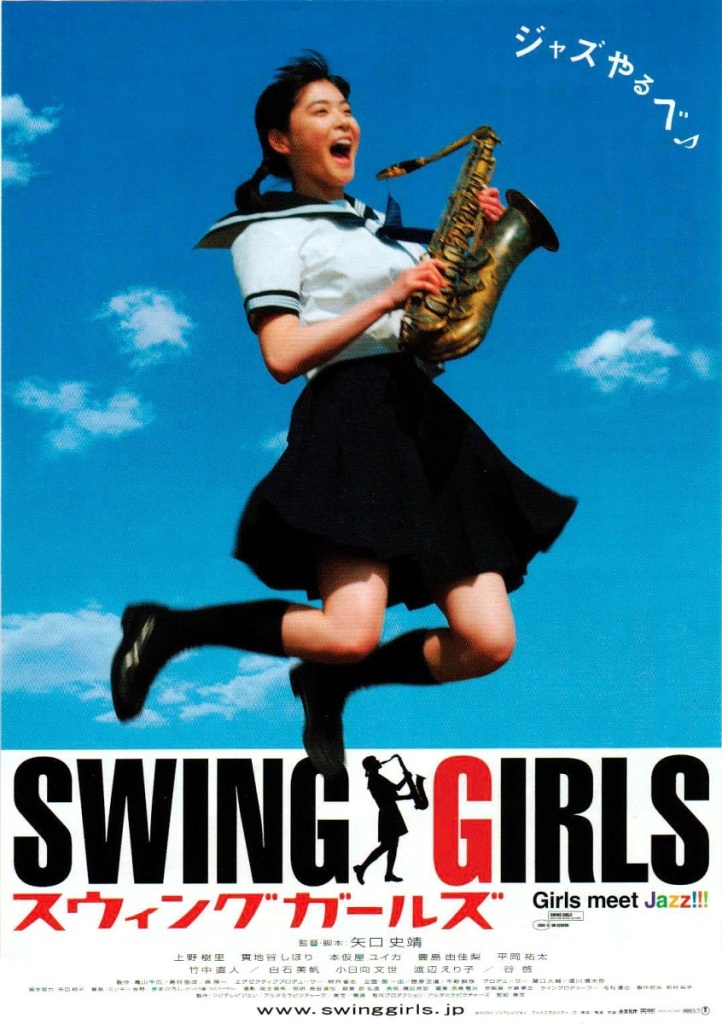

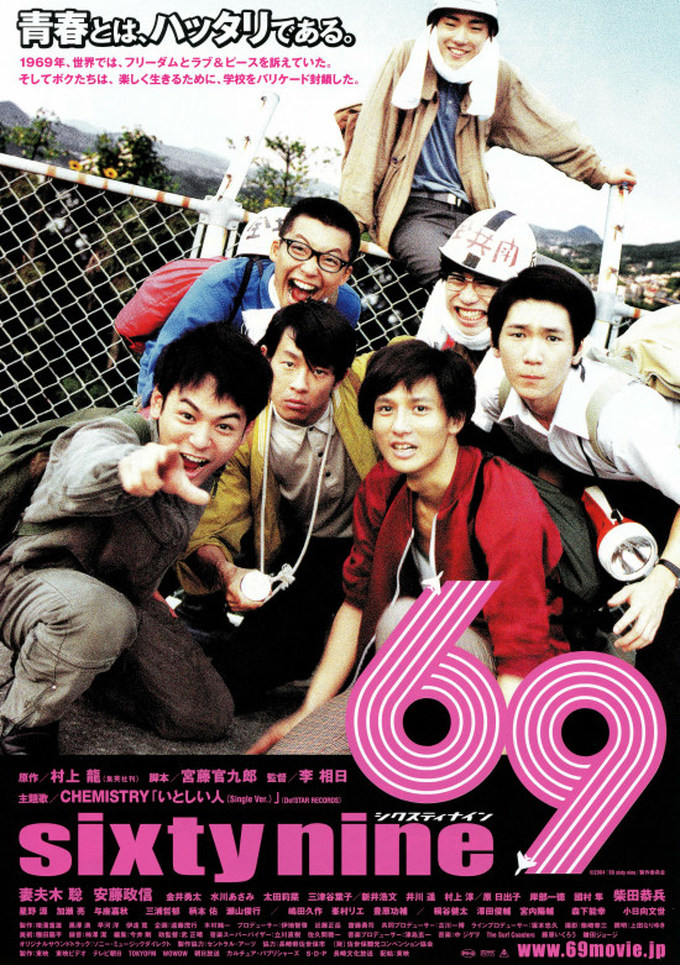

There are two kinds of people in the world, those who swing and those who…don’t – a metaphor which works just as well for baseball and, by implication, facing life’s challenges as it does for music. Shinobu Yaguchi returns after 2001’s  Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story

Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story