By 1961, the Japanese economy had largely recovered and the nation was emerging into an era of rising prosperity, but there were also those who were left behind or could progress into the new Japan. Shot with Okamaoto’s trademark irony, Procurer of Hell (地獄の饗宴, Jigoku no Kyoen) is a darkly comic tale of one such man who could have quit while he was ahead and started a new life if only he hadn’t been so greedy or perhaps so hung up on revenge.

In a sign of the newly international society, Tobe (Tatsuya Mihashi) runs a shady business that claims to provide “English lessons” with blonde women are that are in reality appointments with sex workers. He also peddles pornographic images and dabbles in blackmail. When he finds a roll of film at the station, he gets it developed and discovers it contains photographs of his sergeant during the war, Itami (Jun Tazaki), who raped the Chinese woman he wanted to marry back in Manchuria. Tobe was unable to help her after getting his hand impaled on a tree branch from which he could not free himself. The scar he still bears on his hand is a mark of his corruption and a reminder of the moment which seems to have soured him on humanity and turned him into a cynical and amoral man. He decides to use the photographs to torment and blackmail Itami to get the money to help a widowed single mother he’s interested in secure a better future for herself by taking over a coffee shop from the owner who plans to retire.

As such, he does it for “good” reasons and Kazuko (Junko Ikeuchi) and her son Saburo represent for him a better future in the new Japan in which he would own a photo studio and live a law-abiding life. Saeko (Reiko Dan), Itami’s secretary with whom he was also having an extra-marital affair, is in other ways his opposite number and the representative of the dark side to which Tobe is drawn. Like him, she tries to play the situation to her advantage by playing the innocent before finally throwing her lot in with Tobe and suggesting he help her double-cross Itami so they can run off with the money he embezzled from his company before faking his own death in a convenient train crash. That Tobe extracts sexual favours from Saeko in return for giving her the photos and negatives interferes with the supposed nobility of his quest and apparently pure-hearted love for Kazuko and her little boy, while Saeko gradually shifts from exploited victim to calculating conspirator manipulating Tobe just as he believes himself to be manipulating her.

In any case, it remains true that he could have just settled for the money he needed for the cafe and walked away from this overly complicated situation involving Itami’s legal wife and associates who have actually embezzled the money and want the pictures back because they need Itami to be dead for their plan to work, but he doesn’t. He becomes fixated on getting his fair share of the ill-gotten gains much more than helping Kazuko or getting his revenge against Itami, which wasn’t really much of a revenge anyway considering what Itami had actually done during the war. But on the other hand, Itami seems to have become a rather powerless figure having married into his wife’s family to work in their business while she plots to have him confined to a psychiatric hospital to keep him out of her way. Saeko too is manipulating him. She has no real feelings for Itami and only wants the money, masterminding this whole scheme to get her hands on it with no intention of fleeing abroad with him. Similarly, she plays the victim with Tobe, telling him that Itami paid for her brother’s school fees and that she wants the photos back to avoid her brother or Mrs Itami finding out it about it and feeling hurt.

But while they’re fixating on the 150 million yen embezzled from the business, there are crowds of angry people turning up at the building society Itami runs complaining that their savings have disappeared and wanting to know if they’re going to get the houses they’ve been promised. Tobe walks through the May Day protests calling for better working conditions and higher wages, pointing to the ways this society is still veering off course in deliberately leaving some-people behind by rooting the new economic prosperity in exploitation. Tobe’s assistant wants to join the protest, but Tobe tells him they don’t really belong with the workers because of their nature of their business. The blackmail scam is his revenge not only on Itami but on everything that’s happened to him since the war and this ridiculous post-war society that he nevertheless hopes to join through these immoral means. The song of the canary he buys for Saburo begins to haunt him as a symbol of the wholesome life he might lead, but that life cannot really be won that way. He and Saeko are really two of a kind, she apparently brought low by her unexpectedly genuine feelings for him as even the police, picking him up for something else, leave them bleeding in the street surrounded only by emptiness and futility mere feet from the hospital in their own relentless pursuit of the “real” criminals.

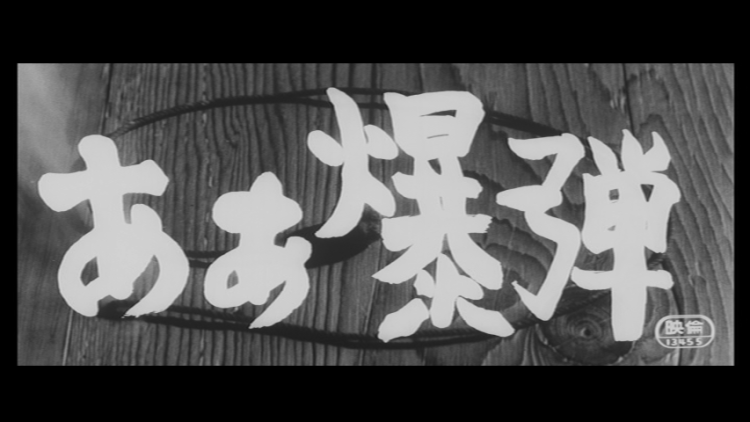

Being stood up is a painful experience at the best of times, but when you’ve been in prison for three whole years and no one comes to meet you, it is more than usually upsetting. Sixth generation Oyabun of the Ona clan, Daisaku, has made a new friend whilst inside – Taro is a younger man, slightly geeky and obsessed with bombs. Actually, he’s a bit wimpy and was in for public urination (he also threw a firecracker at the policeman who took issue with his call of nature) but will do as a henchman in a pinch. Daisaku wanted him to see all of his yakuza guys showering him with praise but only his son actually turns up and even that might have been an accident.

Being stood up is a painful experience at the best of times, but when you’ve been in prison for three whole years and no one comes to meet you, it is more than usually upsetting. Sixth generation Oyabun of the Ona clan, Daisaku, has made a new friend whilst inside – Taro is a younger man, slightly geeky and obsessed with bombs. Actually, he’s a bit wimpy and was in for public urination (he also threw a firecracker at the policeman who took issue with his call of nature) but will do as a henchman in a pinch. Daisaku wanted him to see all of his yakuza guys showering him with praise but only his son actually turns up and even that might have been an accident.