If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to live in hell, you could enjoy this fascinating promotional video which recounts events set in an isolated rural monastery somewhere in snow covered Japan. A debut feature from Tatsushi Omori (younger brother of actor Nao Omori who also plays a small part in the film), The Whispering of the Gods (ゲルマニウムの夜, Germanium no Yoru) adapted from the 1998 novel by Mangetsu Hanamura, paints an increasingly bleak picture of human nature as the lines between man and beast become hopelessly blurred in world filled with existential despair.

If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to live in hell, you could enjoy this fascinating promotional video which recounts events set in an isolated rural monastery somewhere in snow covered Japan. A debut feature from Tatsushi Omori (younger brother of actor Nao Omori who also plays a small part in the film), The Whispering of the Gods (ゲルマニウムの夜, Germanium no Yoru) adapted from the 1998 novel by Mangetsu Hanamura, paints an increasingly bleak picture of human nature as the lines between man and beast become hopelessly blurred in world filled with existential despair.

Rou (Hirofumi Arai) has returned to the religious community where he was raised but his reasons for this seem to have everything and nothing to do with God. He claims that he “kind of killed some people” and also says he’s a rapist, but there’s no way to tell how much of what he says is actually the truth. After opening with a sequence of bulls trudging through snow, we see Rou listening to a priest read from the bible, but we also see that Rou is giving the priest a hand job whilst looking resolutely vacant. Later, after expending some pent-up anger by thrashing around some with junk and kicking a dog, Rou has a heart to heart with a novice nun, Kyoko, which quickly results in a forbidden sexual relationship. Forbidden sexual relationships, well – “relationships” isn’t quite the right word here, perhaps transactions or just actions might be more appropriate, are very much the name of the game in this extremely strange community of runaways and reprobates each keen to pass their own suffering down to another through a complex network of abuse and violence.

An early scene sees Rou throw a metal pipe across his shoulders in an oddly Christ-like pose. He’s certainly no Messiah, he wants to take revenge on these people by being the very worst of them, but ultimately he does come carrying a message. Using the same tools against them as they’ve used against him all his life, he exploits the loopholes of religiosity to expose its inherent hypocrisy. He confesses sins he may or may not have committed as well as those he plans to commit. In giving him unconditional absolution for an uncommitted sin, has the priest just given him a free pass to balance the celestial books by going ahead and violating a random nun? As well as well and truly messing with the resident priest’s head, Rou’s rampant sexuality also exposes the latent longings present within the nuns themselves who are supposed to control their sexual urges, brides of Christ as they are, yet they too covertly indulge themselves in receiving satisfaction from the various kinds of strange sexual behaviour currently on offer.

Life on the farm is nature red in tooth and claw as one particularly brutal scene sees a male pig castrated with a pair of garden shears during a failed act of copulation. Later a pig will lie in neatly dissected pieces, dripping with blood and fluid. There’s no romance here, just flesh and impulse. Forming a kind of friendship with a younger boy, Toru, who is also being abused by the priests at the compound, Rou offers to take revenge for him but it seems the boy just wanted to confide in someone, to begin with. Later, Rou will take a kind of action and Toru offers to repay him by continuing the behaviours he has learned through a system of perpetual manipulation, unwittingly drawing Rou even more deeply into the spiral of abuse and hypocrisy that he set out to destroy.

Omori opts for a straightforward arthouse aesthetic which matches the bleakness of the environment and barrenness of spirituality found in this supposedly Christian commune. In fact, Omori had to go a roundabout route to get this film shown given its controversial nature which saw him set up a temporary marquee theatre to avoid having the film cut to get an Eirin certificate before getting it into more mainstream cinemas in his desired version. What it has to say about the base essence of humanity is extremely hard to take, though no less valid, and its picture of a hellish world filled with nothing but despair punctuated by guilt filled sexual episodes and violence in which there is nothing left to do but continue shovelling shit until you die is an uncomfortably apt metaphor for contemporary society.

Mangetsu Hanamura’s source novel does not appear to be available in English but actually seems to be even more disturbing than this extremely depressing film – more info over at Books From Japan.

Unsubbed trailer:

Kenji Uchida travelled to America’s San Fransisco State University to study filmmaking before returning to Japan and making this, his debut film, Weekend Blues (ウィーク エンド ブルース) which later went on to claim two awards at the prestigious Pia Film Festival for independent films earning him the scholarship which enabled his next film,

Kenji Uchida travelled to America’s San Fransisco State University to study filmmaking before returning to Japan and making this, his debut film, Weekend Blues (ウィーク エンド ブルース) which later went on to claim two awards at the prestigious Pia Film Festival for independent films earning him the scholarship which enabled his next film,  Cyberpunk, for many people, is a movement which came to define the 1980s and continues to enjoy various kinds of resurgences and rebirths even into the new century. Beginning the the ‘60s and ’70s in dystopian science fiction afraid of the impact of advancing technologies in society, it’s not surprising that the genre began to actively embrace influences from the East and especially that of the more technologically advanced and economically superior Japan. However, when Japan made its own cyberunk cinema, the “punk” element is the one that’s important. These movies sprang from the punk music scene and often star punk bands and musicians as well as featuring high energy punk rock inspired scores.

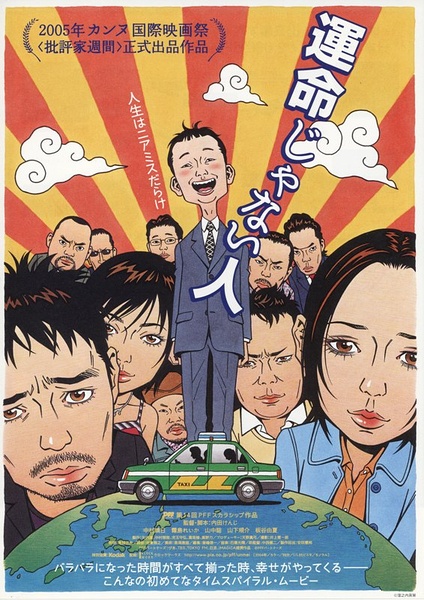

Cyberpunk, for many people, is a movement which came to define the 1980s and continues to enjoy various kinds of resurgences and rebirths even into the new century. Beginning the the ‘60s and ’70s in dystopian science fiction afraid of the impact of advancing technologies in society, it’s not surprising that the genre began to actively embrace influences from the East and especially that of the more technologically advanced and economically superior Japan. However, when Japan made its own cyberunk cinema, the “punk” element is the one that’s important. These movies sprang from the punk music scene and often star punk bands and musicians as well as featuring high energy punk rock inspired scores. Sometimes life throws you a pretty crazy night but unbeknownst to you the whole world has gone crazy too. For the disparate group of people at the centre of Kenji Uchida’s A Stranger of Mine (運命じゃない人, Unmei Janai Hito) , this proves to be more than usually true. A cute romantic encounter may end up going in a less than cinematic direction while ex-girlfriends, detectives and even the yakuza all conspire to frustrate the lovelorn dreams of a nice guy businessman who never even realises the total chaos which is ensuing all around him.

Sometimes life throws you a pretty crazy night but unbeknownst to you the whole world has gone crazy too. For the disparate group of people at the centre of Kenji Uchida’s A Stranger of Mine (運命じゃない人, Unmei Janai Hito) , this proves to be more than usually true. A cute romantic encounter may end up going in a less than cinematic direction while ex-girlfriends, detectives and even the yakuza all conspire to frustrate the lovelorn dreams of a nice guy businessman who never even realises the total chaos which is ensuing all around him. Sogo Ishii (now Gakuryu Ishii) was one of the foremost filmmakers in Japan’s punk movement of the late ‘70s and ‘80s though his later work drifted further away from his youthful subculture roots. Perhaps best known for his absurdist look at modern middle class society in The Crazy Family or his noisy musical epics Crazy Thunder Road and Burst City, Ishii’s first feature length film is a quieter, if no less energetic, effort.

Sogo Ishii (now Gakuryu Ishii) was one of the foremost filmmakers in Japan’s punk movement of the late ‘70s and ‘80s though his later work drifted further away from his youthful subculture roots. Perhaps best known for his absurdist look at modern middle class society in The Crazy Family or his noisy musical epics Crazy Thunder Road and Burst City, Ishii’s first feature length film is a quieter, if no less energetic, effort. Generally speaking, capitalists get short shrift in Western cinema. Other than in that slight anomaly that was the ‘80s when “greed was good” and it became semi-acceptable to do despicable things so long as you made despicable amounts of money, movies side with the dispossessed and downtrodden. Like the mill owners of nineteenth century novels, fat cat factory owners are stereotypically evil to the point where they might as well be ripping their employees heads off and sucking their blood out like lobster meat. Zhang Wei’s Factory Boss (打工老板, Dagong Laoban) however, attempts to redeem this much maligned figure by pointing out that it’s pretty tough at the top too.

Generally speaking, capitalists get short shrift in Western cinema. Other than in that slight anomaly that was the ‘80s when “greed was good” and it became semi-acceptable to do despicable things so long as you made despicable amounts of money, movies side with the dispossessed and downtrodden. Like the mill owners of nineteenth century novels, fat cat factory owners are stereotypically evil to the point where they might as well be ripping their employees heads off and sucking their blood out like lobster meat. Zhang Wei’s Factory Boss (打工老板, Dagong Laoban) however, attempts to redeem this much maligned figure by pointing out that it’s pretty tough at the top too. When examining the influences of classic European cinema on Japanese filmmaking, you rarely end up with Fellini. Nevertheless, Fellini looms large over the indie comedy Choklietta (チョコリエッタ) and the director, Shiori Kazama, even leaves a post-credits dedication to Italy’s master of the surreal as a thank you for inspiring the fifteen year old her to make movies. Full of knowing nods to the world of classic cinema, Chokolietta is a charming, if over long, coming of age drama which becomes a meditation on both personal and national notions of loss.

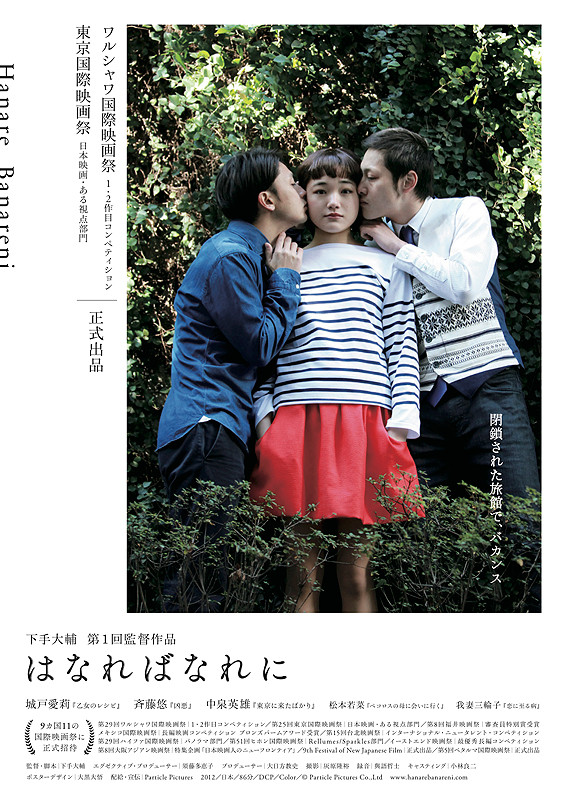

When examining the influences of classic European cinema on Japanese filmmaking, you rarely end up with Fellini. Nevertheless, Fellini looms large over the indie comedy Choklietta (チョコリエッタ) and the director, Shiori Kazama, even leaves a post-credits dedication to Italy’s master of the surreal as a thank you for inspiring the fifteen year old her to make movies. Full of knowing nods to the world of classic cinema, Chokolietta is a charming, if over long, coming of age drama which becomes a meditation on both personal and national notions of loss. All these years later, it’s easy to forget just how revolutionary the wheezy, breezy youthfulness of the French New Wave was. Kuro proves that there’s life in this whimsical, summer seaside feeling yet as three misfits find themselves holing up at a disused small hotel to think about what they’ve done until they learn to grow up a little.

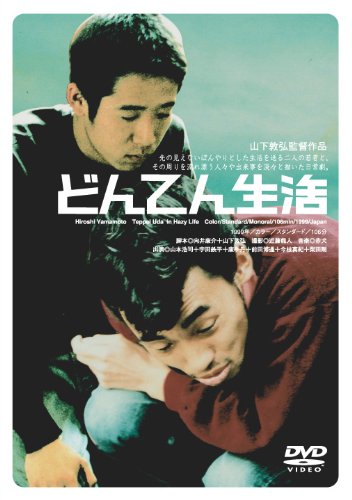

All these years later, it’s easy to forget just how revolutionary the wheezy, breezy youthfulness of the French New Wave was. Kuro proves that there’s life in this whimsical, summer seaside feeling yet as three misfits find themselves holing up at a disused small hotel to think about what they’ve done until they learn to grow up a little. Starting as he meant to go on, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s debut feature film is the story of two slackers, each aimlessly drifting through life without a sense of purpose or trajectory in sight. His humour here is even drier than in his later films and though the tone is predominantly sardonic, one can’t help feeling a little sorry for his hapless, lonely “heroes” trapped in their vacuous, empty lives.

Starting as he meant to go on, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s debut feature film is the story of two slackers, each aimlessly drifting through life without a sense of purpose or trajectory in sight. His humour here is even drier than in his later films and though the tone is predominantly sardonic, one can’t help feeling a little sorry for his hapless, lonely “heroes” trapped in their vacuous, empty lives. These days we think of Sion Sono as the recently prolific, slightly mellowed former enfant terrible of the Japanese indie cinema scene. Hitting the big time with his four hour tale of religion and rebellion Love Exposure before more recently making a case for ruined youth in the aftermath of a disaster in Himizu or lamenting the state of his nation in Land of Hope what we expect of him is an energetic, sometimes ironic assault on contemporary culture. However, his beginnings were equally as varied as his modern output and his first feature length film, Bicycle Sighs (自転車吐息, Jidensha Toiki), owes much more to new wave malaise than to post-punk rage.

These days we think of Sion Sono as the recently prolific, slightly mellowed former enfant terrible of the Japanese indie cinema scene. Hitting the big time with his four hour tale of religion and rebellion Love Exposure before more recently making a case for ruined youth in the aftermath of a disaster in Himizu or lamenting the state of his nation in Land of Hope what we expect of him is an energetic, sometimes ironic assault on contemporary culture. However, his beginnings were equally as varied as his modern output and his first feature length film, Bicycle Sighs (自転車吐息, Jidensha Toiki), owes much more to new wave malaise than to post-punk rage.