Modern life is stressful and perhaps does not offer the kinds of material rewards that previous generations took for granted. Moving back to the country to experience a simpler, more sincere kind of life has become a mini trope in contemporary Japanese cinema as the young men and women of Japan become disillusioned with a stagnating economy and, feeling trapped within a conformist society, decide to embark on a life of self sufficiency free of material burdens. What such stories have not yet asked is if the influx of outsiders from the city amounts to a colonisation of so far untouched land as the newcomers bring with them their newfangled desires and attitudes. Tadashi Nagayama’s gentle satire Being Natural (天然☆生活, Tennen Seikatsu) is partly an attack on rampart xenophobia and small scale colonialism but also a mild condemnation of corporatised hippiedom and its tendency to destroy the thing it claims to honour in remaking it to fit a city dweller’s ideal of idyllic country life.

Modern life is stressful and perhaps does not offer the kinds of material rewards that previous generations took for granted. Moving back to the country to experience a simpler, more sincere kind of life has become a mini trope in contemporary Japanese cinema as the young men and women of Japan become disillusioned with a stagnating economy and, feeling trapped within a conformist society, decide to embark on a life of self sufficiency free of material burdens. What such stories have not yet asked is if the influx of outsiders from the city amounts to a colonisation of so far untouched land as the newcomers bring with them their newfangled desires and attitudes. Tadashi Nagayama’s gentle satire Being Natural (天然☆生活, Tennen Seikatsu) is partly an attack on rampart xenophobia and small scale colonialism but also a mild condemnation of corporatised hippiedom and its tendency to destroy the thing it claims to honour in remaking it to fit a city dweller’s ideal of idyllic country life.

Shy and awkward, Taka (Yota Kawase) is an unemployed middle-aged man who lives with his elderly uncle in the ancestral family home. Taka’s uncle suffers from dementia and, it seems, was always a “difficult” person even in his youth which is perhaps why the rest of the family have abandoned him with only the gentle Taka prepared to stay behind and look after the ageing patriarch. When his uncle dies, Taka’s world threatens to collapse but thankfully his embittered cousin Mitsuaki (Shoichiro Tanigawa) is talked round by his sister and decides to let Taka stay in the family home as a thank you for taking care of everything for so long. Not only that, Mitsuaki also gets Taka a job working at the local fishing pool alongside another old friend, Sho (Tadahiro Tsuru).

Reverting to childhood, the three men generate an easy camaraderie, looking after turtles, having barbecues, and making music together under the moonlight. The idyllic days are not to last, however. The harbingers of doom are a hippyish family from Tokyo who moved into the village with the intention of opening a coffee shop. The Kuriharas – Keigo (Kanji Tsuda), his wife Satomi (Natsuki Mieda), and daughter Itsumi (Kazua Akieda), are into the “natural” way of life and have moved from Tokyo for the benefit of their health. Rather than shop at the supermarket like everyone else, they’re keen to buy from Sho’s grocery store even when he explains to them that all his veg is old and shrivelled rather than freshly plucked from local fields. Still, the family are determined even if it means projecting their vision of “rural life” onto the evident reality.

The Kuriharas are literally intrusive – rudely opening the sliding doors of Taka’s house without permission and waking him up, offering the excuse that they were unable to find the “intercom” on this traditional Japanese house that they claim to admire so much. The original site having fallen through, they’ve set their sights on setting up shop in Taka’s home, exploiting the “traditional” architecture for their warm and welcoming cafe. This is all very well but it does of course mean displacing Taka from his natural habitat. As shy and mild mannered as he is, there’s only so much a man can take and Taka resents being evicted from his family home by a bunch of invading interlopers with commercial concerns.

While Satomi natters on about organic veg, Itsumi skips the English classes her controlling mother makes he go to and guzzles additive loaded instant ramen when she thinks no one’s looking. Wanting to preserve the “natural beauty of glorious Japan”, Keigo goes slightly nuts when he realises Taka’s pet turtles are a non-native breed, exploding with xenophobic fury over the dangerous presence of a disease laden predator whose presence threatens the safety of the true Japanese amphibian. Wondering exactly who or what is the “non native” threat, Taka launches a full scale resistance movement, papering the house in giant graffiti posters reminiscent of the student protest era reminding all that turtles, no matter where they’re from, have a right to life too and must be defended. Yet the corporately minded hippies will stop at nothing to get what they want – manipulating Mitsuaki with a new girlfriend and then turning the town against Taka by means of a heinous, life ruining rumour.

Forced out and heading to the city, Taka is reminded that he is now the hostile foreign element – that the park is not his “home” but belongs to “everyone”. When his beloved bongos are ruptured, Taka’s rage turns radioactive and sends him off on a quest of vengeance only to recede as his better nature regains control and he commits himself to using his new found powers to improve the lives of those around him in small but important ways. A satirical take on the romanticisation of country life by self-interested city dwellers, Being Natural eventually takes a turn for the macabre that possibly undercuts rather than reinforces some of its central concerns but makes a case for according the proper respect to the natural world as well as the people who live within it rather than attempting to exploit it for oneself whilst wilfully ruining it for others.

Being Natural received its international premiere at Fantasia International Film Festival 2018.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

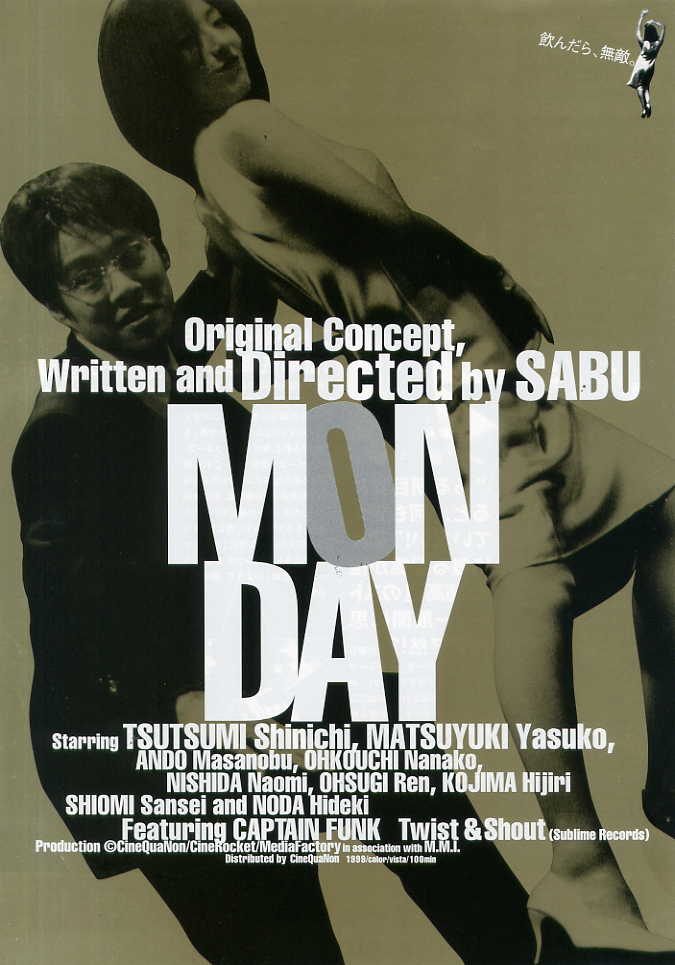

Waking up in an unfamiliar hotel room can be a traumatic and confusing experience. The hero of SABU’s madcap amnesia sit in odyssey finds himself in just this position though he is, at least, fully clothed even if trying to think through the fog of a particularly opaque booze cloud. Monday (マンデイ) is film about Saturday night, not just literally but mentally – about a man meeting his internal Saturday night in which he suddenly lets loose with all that built up tension in an unexpected, and very unwelcome, way.

Waking up in an unfamiliar hotel room can be a traumatic and confusing experience. The hero of SABU’s madcap amnesia sit in odyssey finds himself in just this position though he is, at least, fully clothed even if trying to think through the fog of a particularly opaque booze cloud. Monday (マンデイ) is film about Saturday night, not just literally but mentally – about a man meeting his internal Saturday night in which he suddenly lets loose with all that built up tension in an unexpected, and very unwelcome, way. If you’re going on the run you might as well do it in style. Wait, that’s terrible advice isn’t it? Perhaps there’s something to be said for planning a cunning double bluff by becoming so flamboyant that everyone starts ignoring you out of a mild sense of embarrassment but that’s quite a risk for someone whose original gamble has so obviously gone massively wrong. An adaptation of a manga, Katsuhito Ishii’s debut feature Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl (鮫肌男と桃尻女, Samehada Otoko to Momojiri Onna) follows a mysterious criminal trying to head off the gang he just stole a bunch of money from whilst also accompanying a strange young girl, also on the run but from her perverted, hotel owning “uncle” who has also sent an equally eccentric hitman after the absconding pair with instructions to bring her back.

If you’re going on the run you might as well do it in style. Wait, that’s terrible advice isn’t it? Perhaps there’s something to be said for planning a cunning double bluff by becoming so flamboyant that everyone starts ignoring you out of a mild sense of embarrassment but that’s quite a risk for someone whose original gamble has so obviously gone massively wrong. An adaptation of a manga, Katsuhito Ishii’s debut feature Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl (鮫肌男と桃尻女, Samehada Otoko to Momojiri Onna) follows a mysterious criminal trying to head off the gang he just stole a bunch of money from whilst also accompanying a strange young girl, also on the run but from her perverted, hotel owning “uncle” who has also sent an equally eccentric hitman after the absconding pair with instructions to bring her back. Yoshimitsu Morita had a long standing commitment to creating “populist” mainstream cinema but, perversely, he liked to spice it with a layer of arthouse inspired style. 2002’s Copycat Killer(模倣犯, Mohouhan) finds him back in the realm of literary adaptations with a crime thriller inspired by Miyuki Miyabe’s book in which the media becomes an accessory in the crazed culprit’s elaborate bid for eternal fame through fear driven notoriety.

Yoshimitsu Morita had a long standing commitment to creating “populist” mainstream cinema but, perversely, he liked to spice it with a layer of arthouse inspired style. 2002’s Copycat Killer(模倣犯, Mohouhan) finds him back in the realm of literary adaptations with a crime thriller inspired by Miyuki Miyabe’s book in which the media becomes an accessory in the crazed culprit’s elaborate bid for eternal fame through fear driven notoriety. “What would John do?” is a question Cassavetes loving indie filmmaker Tetsuo (Kiyohiko Shibukawa) often asks himself, lovingly taking the framed late career photo of the godfather of independent filmmaking in America down from the wall. Unfortunately, if Cassavetes has any advice to offer Tetsuo, Tetsuo is not really paying attention. An example of the lowlife scum who appear to have taken over the Japanese indie movie scene, Tetsuo hasn’t made anything approaching art since an early short success some years ago and mainly earns his living through teaching “acting classes” for young, desperate, and this is the key – gullible, people hoping to break into the industry.

“What would John do?” is a question Cassavetes loving indie filmmaker Tetsuo (Kiyohiko Shibukawa) often asks himself, lovingly taking the framed late career photo of the godfather of independent filmmaking in America down from the wall. Unfortunately, if Cassavetes has any advice to offer Tetsuo, Tetsuo is not really paying attention. An example of the lowlife scum who appear to have taken over the Japanese indie movie scene, Tetsuo hasn’t made anything approaching art since an early short success some years ago and mainly earns his living through teaching “acting classes” for young, desperate, and this is the key – gullible, people hoping to break into the industry. You know how it is, you’ve left college and got yourself a pretty good job (that you don’t like very much but it pays the bills) and even a steady girlfriend too (not sure if you like her that much either) but somehow everything starts to feel vaguely dissatisfying. This is where we find Kenji (Ryo Kase) at the beginning of Isao Yukisada’s sewing bee of a movie, Rock ’n’ Roll Mishin (ロックンロールミシン). However, this is not exactly the story of a salaryman risking all and becoming a great artist so much as a man taking a brief bohemian holiday from a humdrum everyday existence.

You know how it is, you’ve left college and got yourself a pretty good job (that you don’t like very much but it pays the bills) and even a steady girlfriend too (not sure if you like her that much either) but somehow everything starts to feel vaguely dissatisfying. This is where we find Kenji (Ryo Kase) at the beginning of Isao Yukisada’s sewing bee of a movie, Rock ’n’ Roll Mishin (ロックンロールミシン). However, this is not exactly the story of a salaryman risking all and becoming a great artist so much as a man taking a brief bohemian holiday from a humdrum everyday existence.