At the end of the second film in the Shinobi no Mono series, Goemon (Raizo Ichikawa) was led away to be boiled alive in oil after failing to assassinate Hideyoshi Toyotomi. Obviously, Goemon did not actually die, but exchanged places with a condemned prisoner thanks to the machinations of Hanzo Hattori (Saburo Date) which is a clear diversion from the accepted historical narrative to which the film otherwise remains more or less faithful. However, in this instalment more than all the others, Goemon is very much a shadow figure, pale and gaunt, who appears much less frequently on screen and mainly relies on stoking the fires of an already simmering succession conflict in the Toyotomi camp.

At this point, Hideyoshi has already made himself de facto leader of a unified Japan having been made the “kampaku”, advisor to the emperor, only to cede that position in favour of his adopted heir, Hidetsugu (Junichiro Narita) taking the title of “Taiko.” Hideyoshi has been childless for many years which is why he adopted his nephew, but the birth of his son by blood has dangerously unbalanced the palace order with Hidetsugu increasingly certain he’s become surplus to requirements. Meanwhile, in an effort to secure his position Hideyoshi has also embarked on an ambitious plan to conquer Korea as a means of getting to Ming China and circumventing the tributary requirements necessary for trading with it.

This plan necessarily means that they need more money with Hideyoshi calling an end to all building and renovation projects including that of a Buddhist temple playing into the series’ themes about hubris in the face of Buddha though by this point Goemon too has lost faith in Buddhism in the clear absence of karmic retribution. As Ieyasu (Masao Mishima) points out, this works out well for him as it will stir discord among local lords who will be forced to squeeze their already exploited subjects even more earning nothing more than their resentment which will then blow back on oblivious Hideyoshi.

Thus Goemon’s role mostly involves sneaking in and telling various people that others are plotting against them and they’d be better to get ahead of it. A secondary theme throughout the series has been a sense of powerlessness which is perhaps inevitable in a historical narrative in which we already know all of the outcomes. Ieyasu scoffs at Goemon, remarking that he thinks he’s walking his own path but is really being manipulated into walking that which Ieyasu has set down for him, though Goemon effectively rejects this stating at the conclusion that as Ieyasu believed he was using him he was also using Ieyasu to achieve his revenge on Hideyoshi for the death of his wife and son. In the historical narrative, Hideyoshi dies of a sudden illness as he does here with Goemon lamenting that his revenge is frustrated by the fact that Hideyoshi is now old and frail though he achieves it through symbolically cutting off his bloodline but explaining to him that Hideyoshi will not become the heir to anything because Ieyasu will be taking the role he has so patiently waited for. Hideyoshi has in any case perhaps disqualified himself as the father of a nation by wilfully sacrificing his adopted son, Hidetsugu, who was ordered to commit suicide to avoid any challenge to Hideyori after becoming desperate and debauched in the knowledge that his days were likely numbered anyway.

In any case, Goemon perhaps declares himself free in asking why he should care who’s in charge after Hanzo once again tries to recruit him to work for a now triumphant Ieyasu whose long years of simply waiting for everyone else to die have paid off. This is what passes for a happy ending in that he has thrown off the corrupt authority of the feudal era and discovered a way to live outside of it as a “free” man though as others point out the system hasn’t changed. Poor peasants continue to be exploited by lords who are greedy but also themselves oppressed by an equally ruler playing petty games of personal power. Fittingly, ninja tricks mainly revolve around smoke bombs and the covert use of noxious fumes to weaken the opposition as they creep in to spread their poison. Never shedding the series’ nihilistic tone, the film ends on a moment of ambivalent positivity albeit one of exile as Goemon declines the invitation to the fold instead wandering off for a life of hidden freedom in the shadows of a still corrupt society.

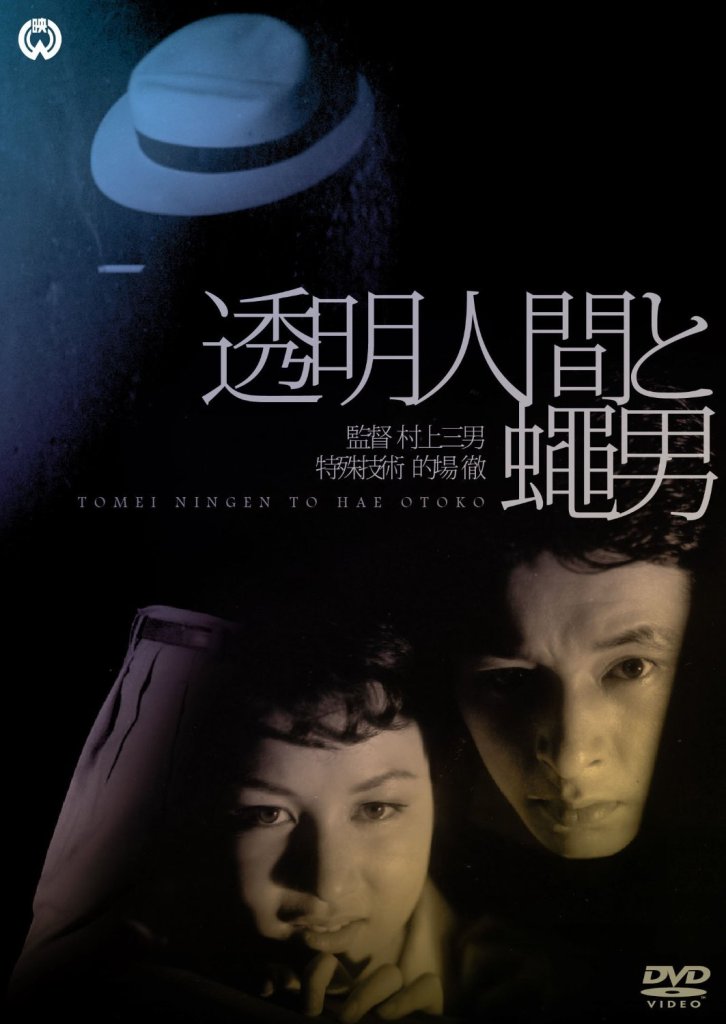

Who would win in a fight between The Invisible Man and The Human Fly? Well, when you think about it, the answer’s sort of obvious and how funny it would be to watch probably depends on your ability to detect the facial expressions of The Human Fly, but nevertheless Daiei managed to make an entire film out of this concept which is a sort of late follow-up to their original take on

Who would win in a fight between The Invisible Man and The Human Fly? Well, when you think about it, the answer’s sort of obvious and how funny it would be to watch probably depends on your ability to detect the facial expressions of The Human Fly, but nevertheless Daiei managed to make an entire film out of this concept which is a sort of late follow-up to their original take on