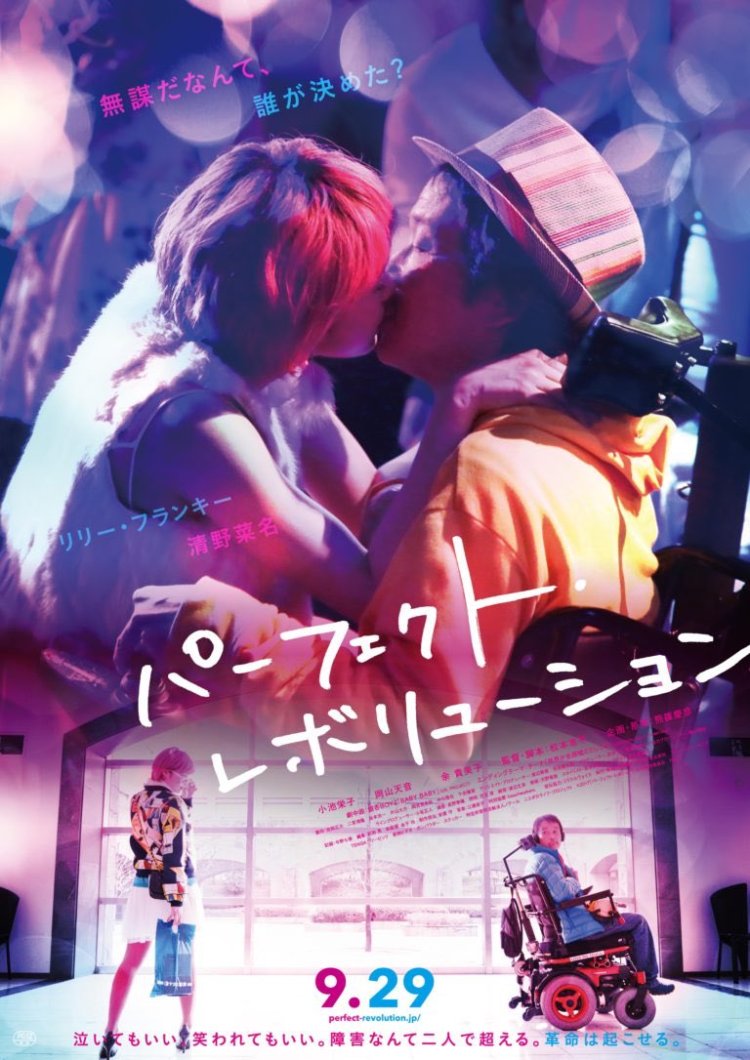

If there is one group consistently underrepresented in cinema, it surely those living with disability. Even the few films which feature disabled protagonists often focus solely on the nature of their conditions, emphasising their suffering or medical treatment at the expense of telling the story of their lives. Junpei Matsumoto’s Perfect Revolution (パーフェクト・レボリューション) which draws inspiration from the real life experiences of Yoshihiko Kumashino – a Japanese man born with cerebral palsy who operates a not for profit organisation promoting awareness of sexual needs among the disabled community, makes a criticism of the aforementioned approach a central pillar of its narrative. Unlike many on-screen depictions of disabled people, Perfect Revolution attempts to reflect the normality of life with a disability whilst never shying away from some of the difficulties and the often hostile attitude from an undereducated society.

If there is one group consistently underrepresented in cinema, it surely those living with disability. Even the few films which feature disabled protagonists often focus solely on the nature of their conditions, emphasising their suffering or medical treatment at the expense of telling the story of their lives. Junpei Matsumoto’s Perfect Revolution (パーフェクト・レボリューション) which draws inspiration from the real life experiences of Yoshihiko Kumashino – a Japanese man born with cerebral palsy who operates a not for profit organisation promoting awareness of sexual needs among the disabled community, makes a criticism of the aforementioned approach a central pillar of its narrative. Unlike many on-screen depictions of disabled people, Perfect Revolution attempts to reflect the normality of life with a disability whilst never shying away from some of the difficulties and the often hostile attitude from an undereducated society.

Kumashiro (Lily Franky), a man in his mid-40s, was born with cerebral palsy and has been using a wheelchair for most of his life. An activist for disabled rights, he’s written a book about his experiences and is keen to address the often taboo subject of sexuality among disabled people. Kumashiro has long since given up on the idea of romance or of forming a “normal” relationship leading to marriage and children but his life changes when a strange pink-haired woman barges into his book signing and demands to know why he’s always talking about sex but never about love. Kumashiro thinks about her question and answers fairly (if not quite honestly as he later reveals) that he doesn’t yet know what love is but is just one of many hoping to find out. This impresses the woman who approaches him afterwards and then refuses to leave him alone. Ryoko (Nana Seino), asking to be known as “Mitsu” (which means “honey” in Japanese – a nice paring with “Kuma” which means “bear”), suddenly declares she’s fallen in love with Kumashiro, whom she nicknames Kumapi.

The elephant in the room is that there is clearly something a little different about Mitsu whose brash, loud manner runs from childishly endearing to worryingly reckless. Mitsu is a sex worker at a “soapland” (a brothel disguised as a bathhouse in which the customer is “washed” by an employee) and sees nothing particularly wrong in her choice of occupation though recognises that other people look down on her because of it – something which she doesn’t quite understand and is constantly exasperated by. Perhaps offensively, she sees her own position as a woman (and a sex worker) as akin to being “disabled” in the kind of social stigma she faces but does not identify as being disabled in terms of her undefined mental health problems beyond accepting that she is “different” and has not been able to integrate into “regular” society. Nevertheless, she believes herself to be at one with Kumashiro in his struggle and is determined to foster the “perfect revolution” with him to bring about true happiness for everyone everywhere.

Thankfully Kumashiro is surrounded by supportive friends and family who are keen to help him manage on his own rather than trying to run his life for him but he does regularly encounter less sympathetic people from a drunken couple who decide to lay into him in a restaurant to a well meaning religious woman who runs after Kumashiro to tell him how “inspired” she feels just looking at him before trying to thrust money into his purse. Mitsu’s problems are less immediately obvious but her loud, volatile behaviour is also a problem for many in conformist Japan as is her straightforwardness and inability to understand the rules of her society. Mitsu has no one to look after her save a fortune teller (Kimiko Yo) who has become a surrogate mother figure, but it is a problem that no one has thought to talk to her about seeing a doctor even when her behaviour turns violent or veers towards self-harm.

Despite their struggles to be seen as distinct individuals, both Kumashiro and Mitsu are often reduced simply to their respective “differences”. Kumashiro does a lot of publicity for his book but is exasperated by well-meaning photographers who ask, tentatively, if they can photograph just his hands – literally reducing him to his disability. An “inspirational” TV documentary strand is also interested in interviewing Kumashiro and Mitsu, but only because of the “unusual” quality of their relationship. It quickly becomes apparent to Kumashiro that the documentarians aren’t interested in documenting his life so much as constructing a narrative around “damaged” outsiders that viewers can feel sorry for. Fearing that Kumashiro looks too cheerful, the producers ask him to remove his makeup and colourful clothing whilst explaining to Mitsu that they don’t want her to talk about sex work in a positive manner and would prefer it if she used a more acceptable euphemism rather than calling it what it is. Mitsu doesn’t realise she’s been had, but Kumashiro leaves the shoot feeling humiliated and annoyed.

Matsumoto does his best to present the issues sensitively, never patronising either Kumashiro or Mitsu but depicting them as real people with real faults just living their lives like everybody else. Neatly avoiding the classic Hollywood, happy ever after ending he emphases that there is still a long way to go but it is unfortunate that Mitsu’s situation is treated more lightly than it deserves and that her eventual desire to get treatment is undermined by the film’s liberated ending which is, nevertheless, inspirational as Kumashiro and Mitsu both commit themselves to the “perfect revolution” of a better, happier future both for themselves and for all mankind.

Screened at Raindance 2017.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

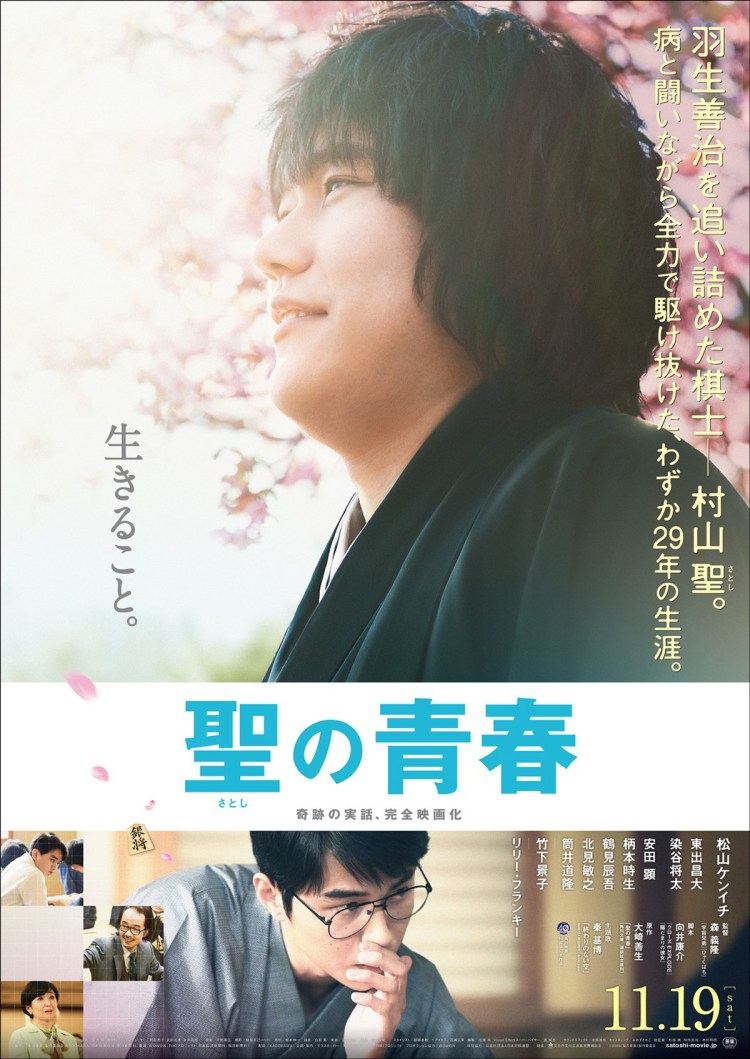

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper.

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper. Hitoshi One has a history of trying to find the humour in an old fashioned sleazy guy but the hero of his latest film, Scoop!, is an appropriately ‘80s throwback complete with loud shirt, leather jacket, and a mop of curly hair. Inspired by a 1985 TV movie written and directed by Masato Harada, Scoop! is equal parts satire, exposé and tragic character study as it attempts to capture the image of a photographer desperately trying to pretend he cares about nothing whilst caring too much about everything.

Hitoshi One has a history of trying to find the humour in an old fashioned sleazy guy but the hero of his latest film, Scoop!, is an appropriately ‘80s throwback complete with loud shirt, leather jacket, and a mop of curly hair. Inspired by a 1985 TV movie written and directed by Masato Harada, Scoop! is equal parts satire, exposé and tragic character study as it attempts to capture the image of a photographer desperately trying to pretend he cares about nothing whilst caring too much about everything. Somewhere near the beginning of Daishi Matsunaga’s debut feature, Pieta in the Toilet (トイレのピエタ, Toire no Pieta), the high rise window washing hero is attempting to school a nervous newbie by “reassuring” him that the worst thing that could happen up here is that you could die. This early attempt at black humour signals Hiroshi’s already aloof and standoffish nature but his fateful remark comes back to haunt him after he is diagnosed with an aggressive and debilitating condition of his own. Noticeably restrained in contrast with the often melodramatic approach of similarly themed mainstream pictures, Pieta in the Toilet is less a contemplation of death than of life, its purpose and its possibilities.

Somewhere near the beginning of Daishi Matsunaga’s debut feature, Pieta in the Toilet (トイレのピエタ, Toire no Pieta), the high rise window washing hero is attempting to school a nervous newbie by “reassuring” him that the worst thing that could happen up here is that you could die. This early attempt at black humour signals Hiroshi’s already aloof and standoffish nature but his fateful remark comes back to haunt him after he is diagnosed with an aggressive and debilitating condition of his own. Noticeably restrained in contrast with the often melodramatic approach of similarly themed mainstream pictures, Pieta in the Toilet is less a contemplation of death than of life, its purpose and its possibilities.

It’s never too late to be what you might have been – a statement attributed to George Eliot which may be as fake as one of the promises offered by the protagonist of Hirokazu Koreeda’s latest attempt to chart the course of his nation through its basic social unit, After the Storm (海よりもまだ深く, Umi yori mo Mada Fukaku). Reuniting Kirin Kiki and Hiroshi Abe as mother and son following their star turns in

It’s never too late to be what you might have been – a statement attributed to George Eliot which may be as fake as one of the promises offered by the protagonist of Hirokazu Koreeda’s latest attempt to chart the course of his nation through its basic social unit, After the Storm (海よりもまだ深く, Umi yori mo Mada Fukaku). Reuniting Kirin Kiki and Hiroshi Abe as mother and son following their star turns in  A Double Life (二重生活, Nijyuu Seikatsu ), the debut feature from director Yoshiyuki Kishi adapted from Mariko Koike’s novel, could easily be subtitled “a defence of stalking with indifference”. As a philosophical experiment in itself, it recasts us as the voyeur, watching her watching him, following our oblivious heroine as she becomes increasingly obsessed with the act of observance. Taking into account the constant watchfulness of modern society, A Double Life has some serious questions to ask not only of the nature of existence but of the increasing connectedness and its counterpart of isolation, the disconnect between the image and reality, and how much the hidden facets of people’s lives define their essential personality.

A Double Life (二重生活, Nijyuu Seikatsu ), the debut feature from director Yoshiyuki Kishi adapted from Mariko Koike’s novel, could easily be subtitled “a defence of stalking with indifference”. As a philosophical experiment in itself, it recasts us as the voyeur, watching her watching him, following our oblivious heroine as she becomes increasingly obsessed with the act of observance. Taking into account the constant watchfulness of modern society, A Double Life has some serious questions to ask not only of the nature of existence but of the increasing connectedness and its counterpart of isolation, the disconnect between the image and reality, and how much the hidden facets of people’s lives define their essential personality. Ryosuke Hashiguchi returns after an eight year absence with All Around Us (ぐるりのこと。Gururi no Koto) and eschews most of his pressing themes up this by point by opting to depict a few “scenes from a marriage” in post-bubble era Japan. Set against the backdrop of an extremely turbulent decade which was plagued by natural disasters, terrorism, and shocking criminal activity Hashiguchi shows us the enduring love of one ordinary couple who, finding themselves pulled apart by tragedy, gradually grow closer through their shared grief and disappointment.

Ryosuke Hashiguchi returns after an eight year absence with All Around Us (ぐるりのこと。Gururi no Koto) and eschews most of his pressing themes up this by point by opting to depict a few “scenes from a marriage” in post-bubble era Japan. Set against the backdrop of an extremely turbulent decade which was plagued by natural disasters, terrorism, and shocking criminal activity Hashiguchi shows us the enduring love of one ordinary couple who, finding themselves pulled apart by tragedy, gradually grow closer through their shared grief and disappointment. Belated review from the 2015 London Film Festival – Yakuza Apocalypse is released in UK cinemas for one day only on 6th January 2016 courtesy of Manga who will also be releasing on home video at a later date.

Belated review from the 2015 London Film Festival – Yakuza Apocalypse is released in UK cinemas for one day only on 6th January 2016 courtesy of Manga who will also be releasing on home video at a later date.

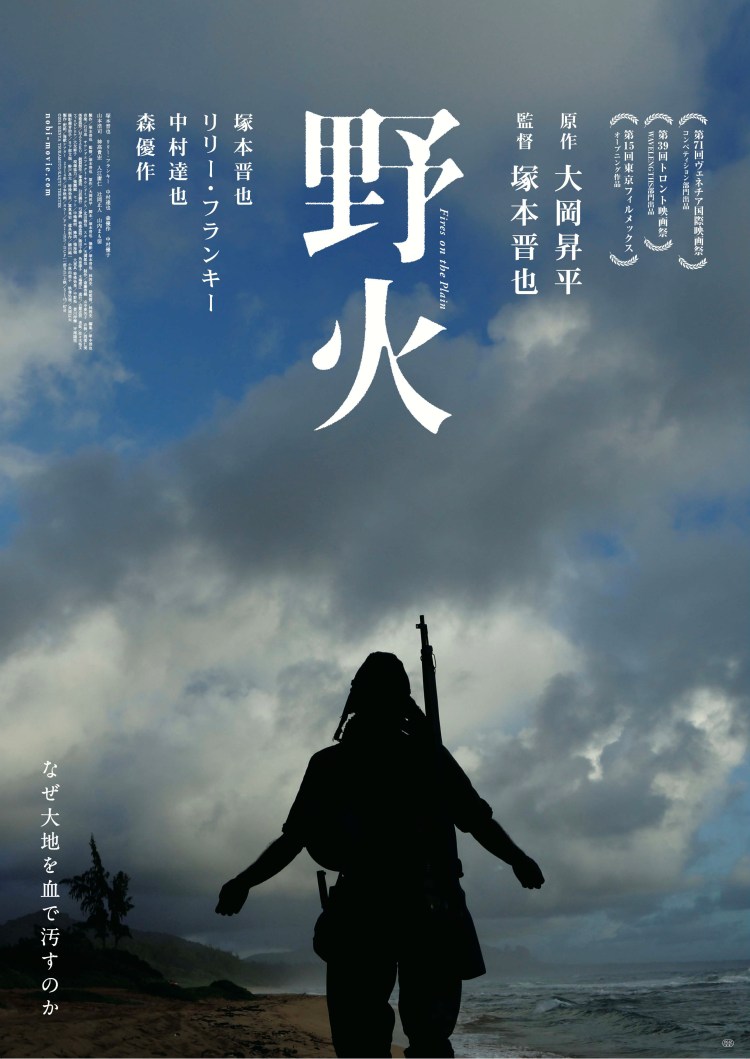

Shinya Tsukamoto is back with another characteristically visceral look at the dark sides of human nature in his latest feature length effort, Fires on the Plain (野火, Nobi). Another take on the classic, autobiographically inspired novel of the same name by Shohei Ooka (previously adapted by

Shinya Tsukamoto is back with another characteristically visceral look at the dark sides of human nature in his latest feature length effort, Fires on the Plain (野火, Nobi). Another take on the classic, autobiographically inspired novel of the same name by Shohei Ooka (previously adapted by