Fleeing a gang war with Columbian drug lords, a Brazilian gangster of Japanese descent tries his luck on the mainland but finds himself a perpetual outsider who can’t get himself taken seriously in Kazuhiro Kiuchi’s moody adaptation of his own manga, Carlos (カルロス). Owing a little bit to Brian De Palma’s Scarface, the tale takes place in a Japan mired in hopelessness and despair amid the spectre of economic collapse, while Carlos tries to play one gang off against another to exploit the terminal decline of the old school yakuza.

What we have here is a succession crisis. The Yamashiro boss (Minoru Oki) is planning to step down due to ill health though in the middle of a long-running dispute with the Hayakawa gang. When two of their guys are randomly killed, they assume only Hayakawa could be behind it little knowing that Carlos (Naoto Takenaka), a Brazilian-Japanese gangster on the run in Japan after killing eight policemen in a gang war in Brazil, killed them because they thought they didn’t need to obey the rules of the underworld with a “foreign” gangster. “We don’t need to treat those Brazilians as equals,” one says while already late to their appointed meeting. They haven’t paid Carlos for the guns he sold them, and when challenged, try to intimidate him into giving them away for free. But Carlos is sick of being intimidated and bumps them off himself.

Carlos faces constant microaggressions about not being Japanese enough, though he speaks the language fluently without an accent. “Your crude taste doesn’t fly in Japan,” a yakuza tells him, criticising his outfit for being too informal when yakuza of this era generally dress in fancy suits and style their hair with military precision. That’s not really something that bothers Carlos, but he’s annoyed to be so easily dismissed and it’s true enough that he’s being used because they think he’s disposable. Not only is he not a “yakuza”, but as they don’t see him as Japanese either, they don’t need to accord him even the dignity they’d grant to a gang member. When Katayama hires Carlos to knock of his rival for the succession, Sato, he’s pissed off when Carlos takes things too far and puts on a show that threatens to blow the whole thing wide open by massacring Sato’s guys at baseball practice. To a man like Katayama, this is total idiocy and attributable to Carlos’ foreignness, both in his capacity for unnecessary violence and his lack of understanding of the rules of Japanese gangsterdom.

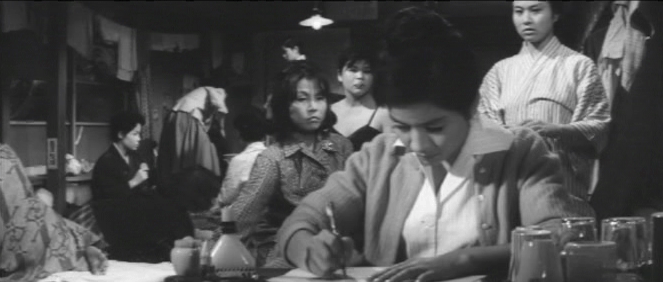

But the one place Carlos and his brother Antonio are fully Japanese is in the home of his aunt who also migrated from Brazil and their Japanese-born cousin Tomomi. Carlos’ aunt refers to them both by their Japanese names, Shiro and Goro, and cooks them Japanese food like sukiyaki. This pleasant domestic environment seems to represent a more settled life Carlos could have found outside of a crime family, especially as his brother Antonio grows closer to Tomomi, but there are also hints of darkness in his uncle’s early death from cirrhosis of the liver which suggests he may have had a hard life in Japan and taken to drink. Nevertheless, his aunt seems to have made a nice life for herself and her daughter and is overjoyed to expand her family by welcoming Carlos and Antonio.

Yet this sort of life seems outside of Carlos’ reach while he continues to play the yakuza gangs off against each other while simultaneously longing for some kind of recognition and almost willing them to figure out it was him who killed Sugita and Yano, the obnoxious Yamashiro guys. Meanwhile, the weakened yakuza have also turned to a foreign hitman, a brooding and robotic American who lacks compassion or compunction and unlike Carlos seems to be a mindless killing machine. When Carlos bests him, it’s an eerie moment echoing Blue Velvet as his body rocks and then falls. By contrast, when Carlos fights his way to the head of the Yamashiro gang, Yamashiro gets puffed up and draws his sword swearing he’ll teach Carlos what a mistake it is to underestimate the Japanese mob, only Carlos simply shoots him in a moment of clear victory over this outdated adherence to a traditional code. Nevertheless, it’s clear that Carlos can’t win here either and there is no room in Japan for a man like him. His only option is to go out all guns blazing as a means of validating himself as a force to be reckoned with, someone who was worthy of attention and of being taken seriously. Shot by the legendary Seizo Sengen, Kiuchi’s manga-informed compositions dissolve into visions of loneliness and despair but in its final moments reaches a crescendo of defiance if discovered only in futility.