“Life is long. We all have some regrets.” a grieving widow is told by a disingenuous doctor in full damage limitation mode. He’s not necessarily wrong, nor is his advice that the widow’s pointless quest to retrieve her late husband’s amputated limb has little practical value though of course it means something to her and as he’d pointed out seconds earlier a physician’s duty is to alleviate suffering of all kinds. Apparently inspired by the true story of director Chang Yao-sheng’s mother, A Leg (腿, Tuǐ) is in many ways a story of letting go as the deceased man himself makes a presumably unheard ghostly confession while his wife attempts to do the only thing she can in order to lay him to rest.

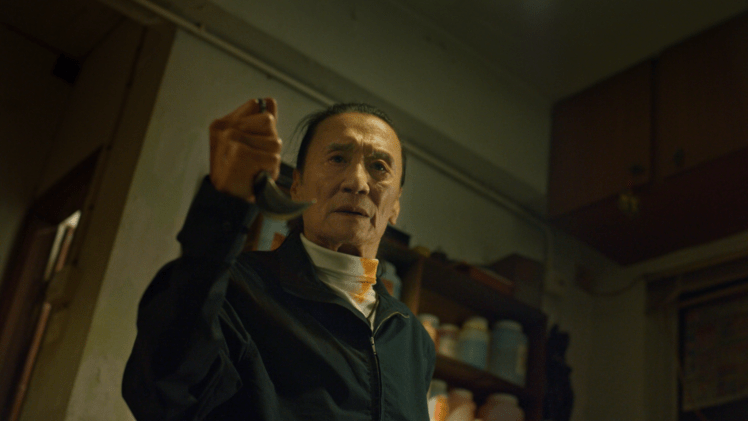

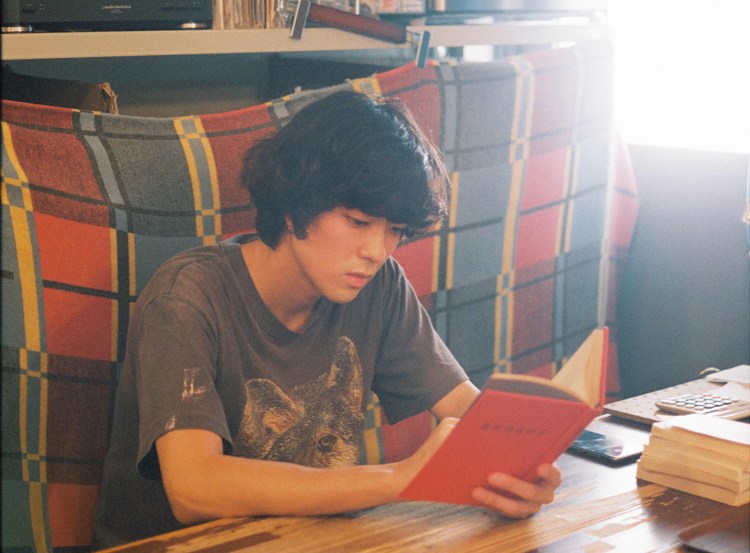

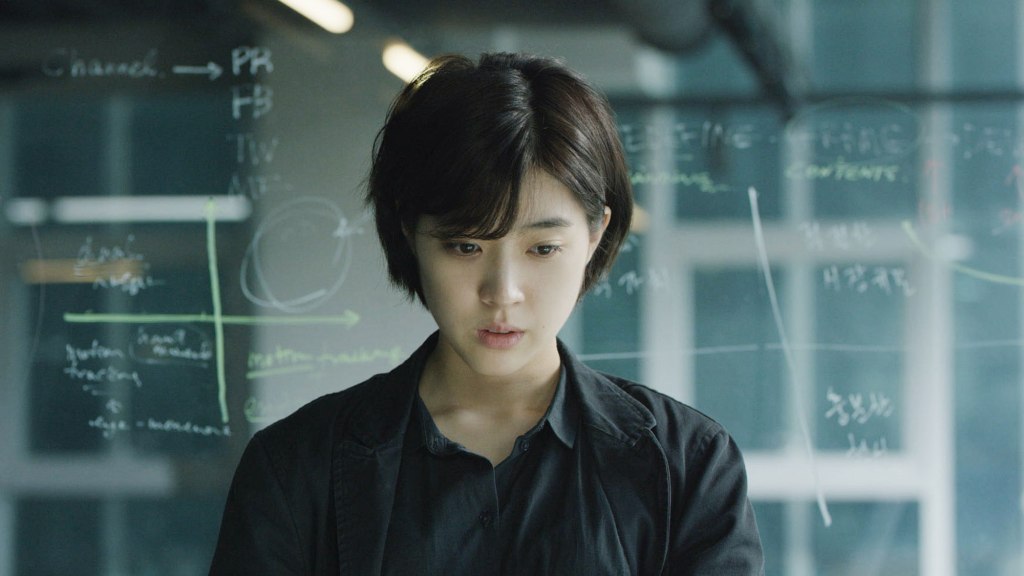

Husband Zi-han (Tony Yang) is in hospital to deal with a painful, seemingly necrotic foot which eventually has to be amputated in a last ditch attempt to cure his septicaemia. “Keep the leg and lose your life, or keep your life and lose the leg” the otherwise unsympathetic doctor advices wife Yu-ying (Gwei Lun-mei) in a remark which will come to seem ironic as, unfortunately, Zi-han’s case turns out to be more serious than first thought and he doesn’t make it through the night. Grief-stricken, Yu-ying leaves in an ambulance with the body but later turns back, determined to retrieve the amputated foot in order that her husband be buried “complete” only it turns out that it’s not as simple as she assumed it would be.

The loss of Zi-han’s foot is all the more ironic as the couple had been a pair of ballroom dancers. As Yu-ying makes a nuisance of herself at the hospital, Zi-han begins to narrate the story of their romance which began when he fell in love with a photo of her dancing in the window of his friend’s photography studio. Explaining that, having died, he’s reached the realisation that everything beautiful is in the past only he was too foolish to appreciate it, Zi-han looks back over his tragic love story acknowledging that he was at best an imperfect husband who caused his wife nothing but pain and disappointment until the marriage finally broke down. He offers no real explanation for his self-destructive behaviour save the unrealistic justification that he only wanted Yu-ying to live comfortably and perhaps implies that his death is partly a means of freeing her from the series of catastrophes he brought into her life.

Given Zi-han’s beyond the grave testimony, the accusation levelled at Yu-ying by his doctor that the couple could not have been on good terms because Zi-han must have been ill for a long time with no one to look after him seems unfair though perhaps hints at the guilt Yu-ying feels in not having been there for her husband when he needed her. As we later discover, however, this is also partly Zi-han’s fault in that he over invested in a single piece of medical advice and resisted getting checked out by a hospital until he managed to sort out an insurance scam using his photographer friend, wrongly as it turned out believing he had a few months slack before the situation became critical and paying a high price for his tendency to do everything on the cheap. Nevertheless, Yu-ying’s quest to reattach his leg is her way of making amends, doing this one last thing for the husband whom she loved deeply even though he appears to have caused her nothing but misery since the day they met.

In order to placate her, the slimy hospital chief offers to have a buddhist sculptor carve a wooden replica of Zi-han’s leg made from wood destined for a statue of Guan-yin goddess of mercy but Yu-ying eventually turns it down, struck by the beauty of the object but convinced that turning it to ash along with her husband’s body would be wrong while believing that wood ash and bone ash are fundamentally different. She regrets having ticked the box on the consent form stating she didn’t want to keep the “specimen”, never for one moment assuming that her husband would not recover. Despite their dancing dreams, she thought the leg was worth sacrificing against the long years they would have spent together after, though this too seems a little unlikely considering the state of their relationship prior to her discovery of Zi-han’s precarious health. Zi-han meanwhile is filled with regret for his continually awful behaviour and the obvious pain he caused his wife. Getting his leg back allows him to begin “moving on” while doing something much the same for Yu-ying though his afterlife pledge about the endurance of love seems a little trite given how he behaved while alive. A little more maudlin than your average quirky rom-com, A Leg nevertheless takes a few potshots at a sometimes cold, cynical, and inefficient medical system, inserting a plea for a little more empathy from a pair of unexpectedly sympathetic police officers, while insisting that it’s important to dance through life with feeling for as long as you’re allowed.

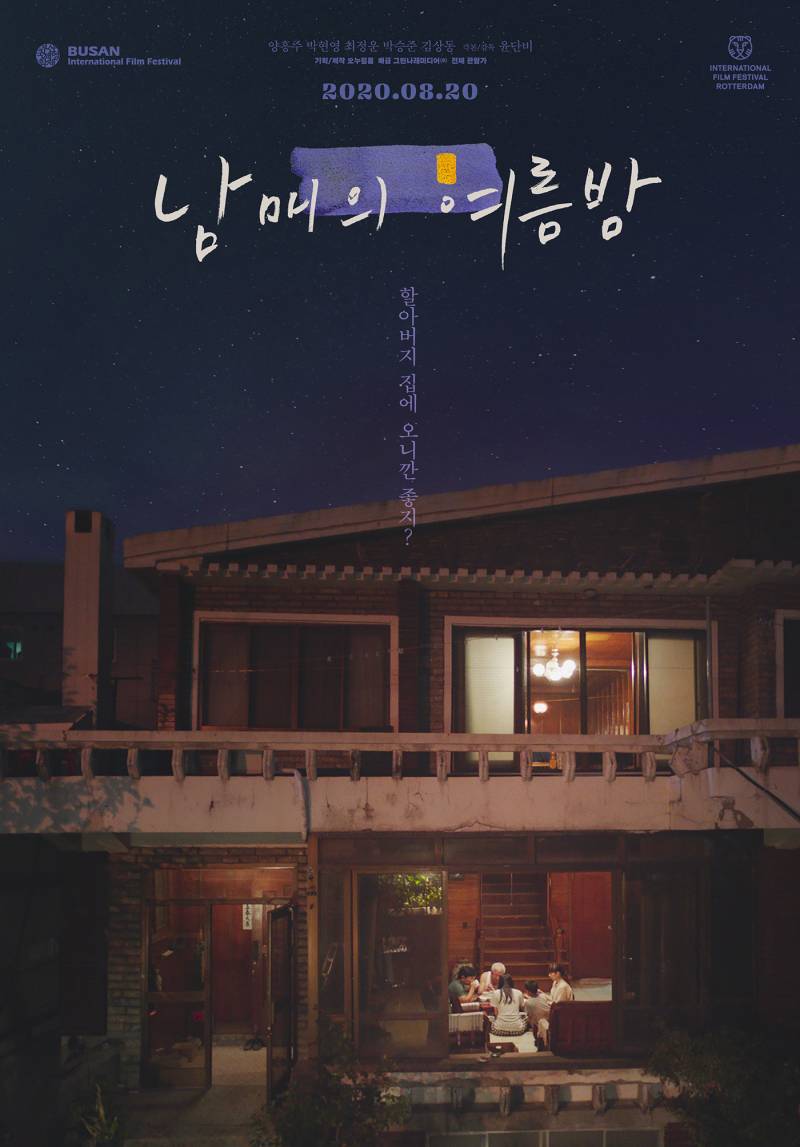

A Leg screens Aug. 14 & streams in the US Aug. 15 – 20 as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (English/Traditional Chinese subtitles)