The latest in a recent series of films critical of Japan’s contemporary employment culture, Sho Miyake’s All the Long Nights (夜明けのすべて, Yoake no Subete) presents a more compassionate working environment as key to a happy and fulling life brokered by small acts of attentive kindness in the knowledge that we are all carrying heavy burdens. Based on a novel by Maiko Seo, the film captures a sense of serenity that can be found in the wonder of life itself and the discovery of the “infinite vastness beyond the darkness” that a starry sky presents.

A lack of compassion in the generalised society is signalled early on in the fact that the heroine, Misa (Mone Kamishiraishi), struggles with a condition that is little understood and belittled by those around her. On bonding with workplace colleague Takatoshi (Hokuto Matsumura) who is experiencing panic disorder, he dismisses her issues as “that female thing” and suggests it doesn’t compare to the effects his condition is having on his life. She counters him that she didn’t know there was a ranking, but is obviously rankled by the refusal of the world around her to take her PMS seriously even though it causes her to lash out at others and often ruins employment opportunities because it’s impossible for her to regulate her emotions in the way that is generally expected in contemporary working culture.

Each of them have ended up working at a small company that manufactures scientific instruments for children after originally working in larger corporate structures with very clear hierarchical systems and rigid modes of behaviour. Yet we can see right away that Misa’s colleagues are aware of her condition and seem to have accepted it. When she blows up at Takatoshi over his habit of drinking carbonated water the sound of which gets on her nerves, they gently steer her away while explaining to him not to pay it any mind. In any case, Misa is still embarrassed by her behaviour and regularly buys pastries at a nearby bakery in an act of continual atonement even though her boss tells her not to get into the habit of it.

Takatoshi’s rather rude refusal of her pastries, clumsily explaining that he dislikes raw cream, is another symptom of his aloofness and unwillingness to be a part of the office community. He is continually looking to get his old job back and looks down on this kind of work as being lower in status than a regular office job at a big company, something perhaps reinforced by his well-meaning girlfriend who seems to want him not only to get better but to reassume his former position despite the implication that it’s what made him ill in the first place. Tsujimoto (Kiyohiko Shibukawa), his former boss, however remains compassionate and supportive perhaps in part because his older sister took her own life due to workplace pressures which has made him more sensitive to the troubles of those around him. That’s also true of the boss of the science company, Kurita (Ken Mitsuishi), whose younger brother also took his own life for unclear reasons leaving him acutely aware of the importance of paying attention to the feelings of others.

It’s in this compassionate environment that Misa and Takatoshi each begin to rediscover a new sense of confidence in their mutual solidarity regarding their personal struggles along with a better idea of what kind of life suits them rather than focusing on how they’re seen by others or living up to a societal notion of what defines conventional success. As they’re tasked with creating a voiceover script for the company’s mobile planetarium, they come to an appreciation of the beauty found in darkness along with the light that shines within it in. As Misa reflects, there is nothing in life that does not change, not even the stars, but amid all that anxiety we can still help each other and live peaceful, quietly profound lives finding fulfilment in the mundane. Shot in a hazy, slightly detached naturalism the film eventually finds a joy in life’s simplicity and the warmth of human connection that exists outside of the corporate superstructures that have come to define most of our lives while otherwise robbing us of the ability to fully embrace it or ourselves.

All the Long Nights screened as part of this year’s Toronto Japanese Film Festival

Original trailer (English subtitles)

A samurai’s soul in his sword, so they say. What is a samurai once he’s been reduced to selling the symbol of his status? According to Scabbard Samurai (さや侍, Sayazamurai) not much of anything at all, yet perhaps there’s another way of defining yourself in keeping with the established code even when robbed of your equipment. Hitoshi Matsumoto, one of Japan’s best known comedians, made a name for himself with the surreal comedies Big Man Japan and

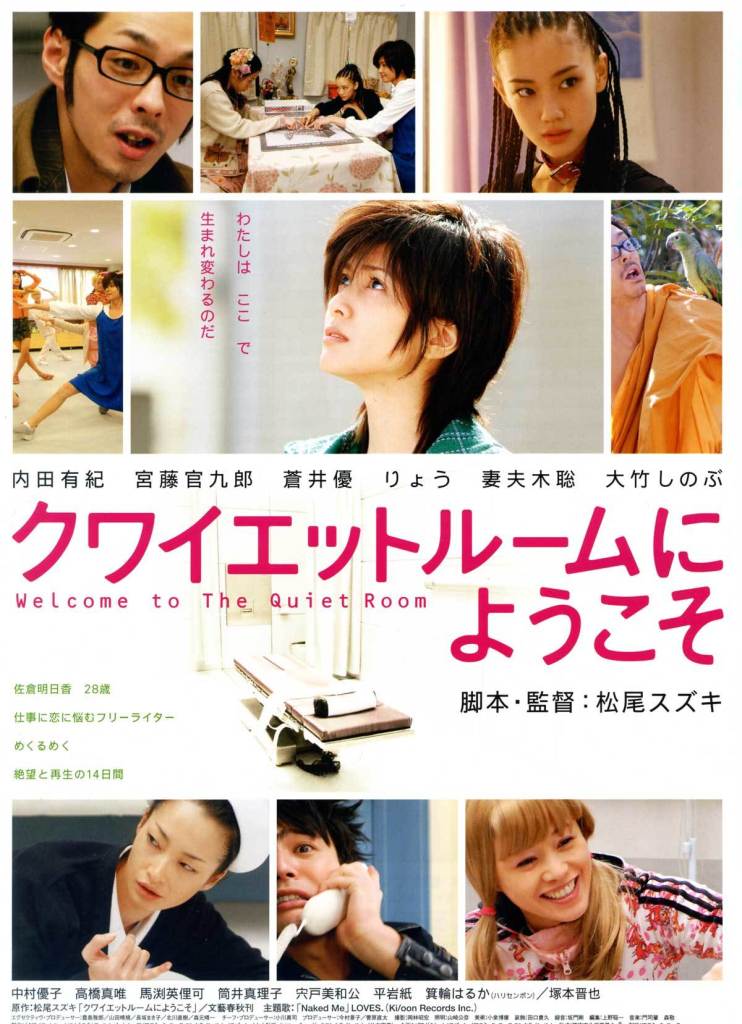

A samurai’s soul in his sword, so they say. What is a samurai once he’s been reduced to selling the symbol of his status? According to Scabbard Samurai (さや侍, Sayazamurai) not much of anything at all, yet perhaps there’s another way of defining yourself in keeping with the established code even when robbed of your equipment. Hitoshi Matsumoto, one of Japan’s best known comedians, made a name for himself with the surreal comedies Big Man Japan and  Everyone has those little moments in life where you think “how did I get here?”, but thankfully most of them do not occur strapped to a table in an entirely white, windowless room. This is, indeed, where the heroine of Suzuki Matsuo’s adaptation of his own novel Welcome to the Quiet Room (クワイエットルームにようこそ, Quiet Room ni Yokoso) finds herself after a series of events she can’t remember but which seem to have involved pills and booze. A much needed wake up call, Asuka’s spell in the Quiet Room provides a long overdue opportunity to slow down and take a long hard look at herself but self knowledge can be a heavy burden.

Everyone has those little moments in life where you think “how did I get here?”, but thankfully most of them do not occur strapped to a table in an entirely white, windowless room. This is, indeed, where the heroine of Suzuki Matsuo’s adaptation of his own novel Welcome to the Quiet Room (クワイエットルームにようこそ, Quiet Room ni Yokoso) finds herself after a series of events she can’t remember but which seem to have involved pills and booze. A much needed wake up call, Asuka’s spell in the Quiet Room provides a long overdue opportunity to slow down and take a long hard look at herself but self knowledge can be a heavy burden. You know how it is, you’ve left college and got yourself a pretty good job (that you don’t like very much but it pays the bills) and even a steady girlfriend too (not sure if you like her that much either) but somehow everything starts to feel vaguely dissatisfying. This is where we find Kenji (Ryo Kase) at the beginning of Isao Yukisada’s sewing bee of a movie, Rock ’n’ Roll Mishin (ロックンロールミシン). However, this is not exactly the story of a salaryman risking all and becoming a great artist so much as a man taking a brief bohemian holiday from a humdrum everyday existence.

You know how it is, you’ve left college and got yourself a pretty good job (that you don’t like very much but it pays the bills) and even a steady girlfriend too (not sure if you like her that much either) but somehow everything starts to feel vaguely dissatisfying. This is where we find Kenji (Ryo Kase) at the beginning of Isao Yukisada’s sewing bee of a movie, Rock ’n’ Roll Mishin (ロックンロールミシン). However, this is not exactly the story of a salaryman risking all and becoming a great artist so much as a man taking a brief bohemian holiday from a humdrum everyday existence.