Tai Kato joined Toei’s Kyoto studio in 1956 having made his directorial debut at the independent production house Takara Productions in 1951 shortly after being letting go from Daiei in 1950 during the Red Purge (he had been chief secretary for studio’s the labour union). Heavily influenced by and a great admirer of Daisuke Ito, Kato had a passion for chanbara and jidaigeki which were Toei’s mainstays at the time, but even while making what were essentially programme pictures his approach was anything but conventional. With 1958’s Wind, Woman, and Road (風と女と旅鴉, Kaze to Onna to Tabigarasu), Kato embarked on what would become a signature style of “realistic” period drama otherwise at odds with the formulaic nature of the genre.

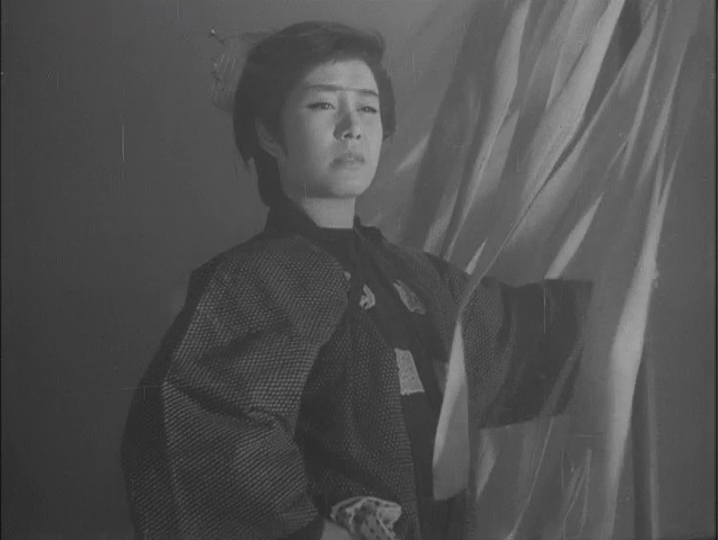

As he would continue to do, Kato instructed his cast not to wear makeup and while casting kabuki actor/chanbara megastar Kinnosuke Nakamura insisted on a more modern performance style than the sometimes mannered theatricality of the traditional samurai film. Ginji is cocksure young man living on the road after being kicked out of the hometown he is now travelling towards because of a crime supposedly committed by his long absent father. On the way, he runs into Sentaro (Rentaro Mikuni), a middle-aged man recently released from prison who is struck by his appearance and immediately asks how old he is realising that Ginji is about the same age as his own son who died as a result of a fight.

The two begin walking together and Ginji tells Sentaro that his village sends gold to the governor around this time every year as a bribe to get lower taxes which doesn’t make a lot of economic sense but evidently works for them. Last year, the gold was stolen by notorious bandit Hanzo the Shark (Eitaro Shindo) and two villagers were killed during the robbery. Ginji half jokes about teaming up to steal it, and then playfully attacks Sentaro leading the entourage escorting this year’s payment to flee in terror leaving the gold behind. Sentaro encourages Ginji to take the money back to the village, but he is later shot by the returning villagers who think they must be Hanzo’s henchmen pulling the same stunt as last year.

Unlike the typical chanbara hero, Ginji is petulant and resentful. He has a very modern way of speaking and is rebellious in character as you might well expect him to be given his life experiences. The other villagers are not happy to see him and continue tar him with his father’s brush, sure that the son of a thief can’t be any better while Ginji pines for his late mother claiming that the villagers’ harassment along with the inability to support herself economically led her to take her own life. Once a member of Hanzo’s gang he vacillates between a desire to be accepted by the village and that to take his revenge on it. Sentaro meanwhile is determined to save him, regretful that he could not save his own son from the life that he had led as a yazkuza and petty criminal.

There is a persistent sense that everyone here is at heart a wanderer. The doctor’s daughter Ochika (Yumiko Hasegawa) who develops a fondness for both men relates that she was lured away from the village by an itinerant actor and fell into a life of ruin before returning to discover that her mother had passed away. The headman’s adopted daughter Oyuki (Satomi Oka) with whom Ginji falls in love tells him that she too is an orphan, her father was a medicine pedlar who dropped dead in the village which then took her in. Echoing a sense of rootlessness in the post-war world, they are all in someway displaced and looking to restore connections which have previously been broken but largely failing or unable to do so. Ginji is torn between his criminal past and the reformed future offered to him by the more positive paternal relationship he develops with Sentaro who, unlike his own father, is readily accepted by the village which is unaware that he previously spent time in prison.

The final showdown takes place in a windswept clearing filled with Kato’s trademark mist as Ginji finally picks a side only to realise that that in the end he will always be a wanderer, a rootless figure whose only home is the road. Kato shoots a little higher than he would subsequently but still rests a little lower than the norm, emphasising a sense of destabilisation in Ginji’s volatility along with a painful longing that keeps him a lonely soul lost in the fog and on perpetual journey towards a long forgotten home.