A meditation on lost love and middle-aged regret, Jun Ichikawa’s Tokyo Lullaby (東京夜曲, Tokyo Yakyoku) weaves a melancholy path through a lonely city but finds in it a sense of comfort or perhaps serenity in the gentle rhythms of ordinary lives that somehow become something greater. A diffident translator in love with an unhappily married middle-aged woman slowly uncovers a deep well of unresolved longing largely thanks to those around him who will remember for those who do not wish to speak.

Ichikawa signals his intentions early on, transitioning from a nighttime shot of the city to a small cafe where a woman is sitting in the foreground looking forlorn while customers behind her discuss the reappearance of Koichi (Kyozo Nagatsuka), the son of the man who owns the electronics store opposite, who had walked out on his family several years previously but has abruptly returned. From this short scene, we can perhaps infer that there is some connection between Koichi and the woman, Tami (Kaori Momoi), though we aren’t quite sure what it is. In any case, the cafe, which bears the name of her late husband Osawa, becomes a kind of nexus uniting the lives of the various community members who each come there to play go and discuss the past.

Like Tami, Koichi is reticent and melancholy. He says nothing of where he’s been and his wife, Hisako (Mitsuko Baisho), asks him no questions. She later tells the writer, Tei, whose affections she does not return, that she doesn’t really care about how Koichi is living his life because she is busy living her own and likes to do as she pleases. His sister asks him if he plans to stay this time, but Koichi can’t answer her seemingly uncomfortable in himself and unable either to stay or to go. Walking on crutches his injured foot seems to symbolise his emotional unsteadiness literally unable to find sure footing or move forward with his life.

Piecing the tale together, Tei figures out that Koichi and Tami were once together but she suddenly married someone else who had a terminal illness and passed away shortly afterwards around the time that Koichi first went walkabout. Hisako, meanwhile, had been in love with Osawa though he loved Tami who did not love him. Somehow it’s all very complicated and incredibly simple, the way they’ve sabotaged their own lives and happiness though it couldn’t have been any other way. Tei watches something similar play out in the neighbourhood. One of the young men who works at the electronics shop had been dating a girl who worked at the record store, but he abruptly begins pursuing Ng, a Chinese woman who works at the cafe, and eventually marries her leaving the record store girl heartbroken.

Things change and they stay the same. Ng takes over the cafe, Koichi’s foot heals while he also manages to resurrect the family business by turning it into a shop that video games as if taking a symbolic step into modernity that suggests this time he’ll stay just as Tami decides it’s time for her to leave. Paths cross endlessly, Ichikawa frequently cutting away to tiny vignettes of other cafe goers as their stories weave through each other, each one note in the great symphony of the city without which life would be impossible. Yet what’s more important is what is not said, the silences that exist between people and perhaps within them too. Things that are understood, and those which are not.

Tami explains that she looked for answers but all she found was junk until the relief of boredom became her only frame of happiness. Only by escaping the city does it seem that she’ll be happy while Koichi seems as if he’s getting itchy feet and Tei, joining the cycle, decides to move on rather than remain in painful proximity to Hisako who as she said has her own life and does not seem to want to share it with anyone much less him. The pain of the past cannot fully be healed, only borne amid the cheerful scenes of city life, children playing, people doing business, the sun shining and elderly couples meeting in cafes. Pain and loneliness seem to be the natural conditions of urbanity, but Ichikawa paints them with a kind of rosiness, merely the sadness that unpins the lullaby of a city which is always changing yet remains the same in its unwalled alleyways and those that exist only in the deepest recesses of memory.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

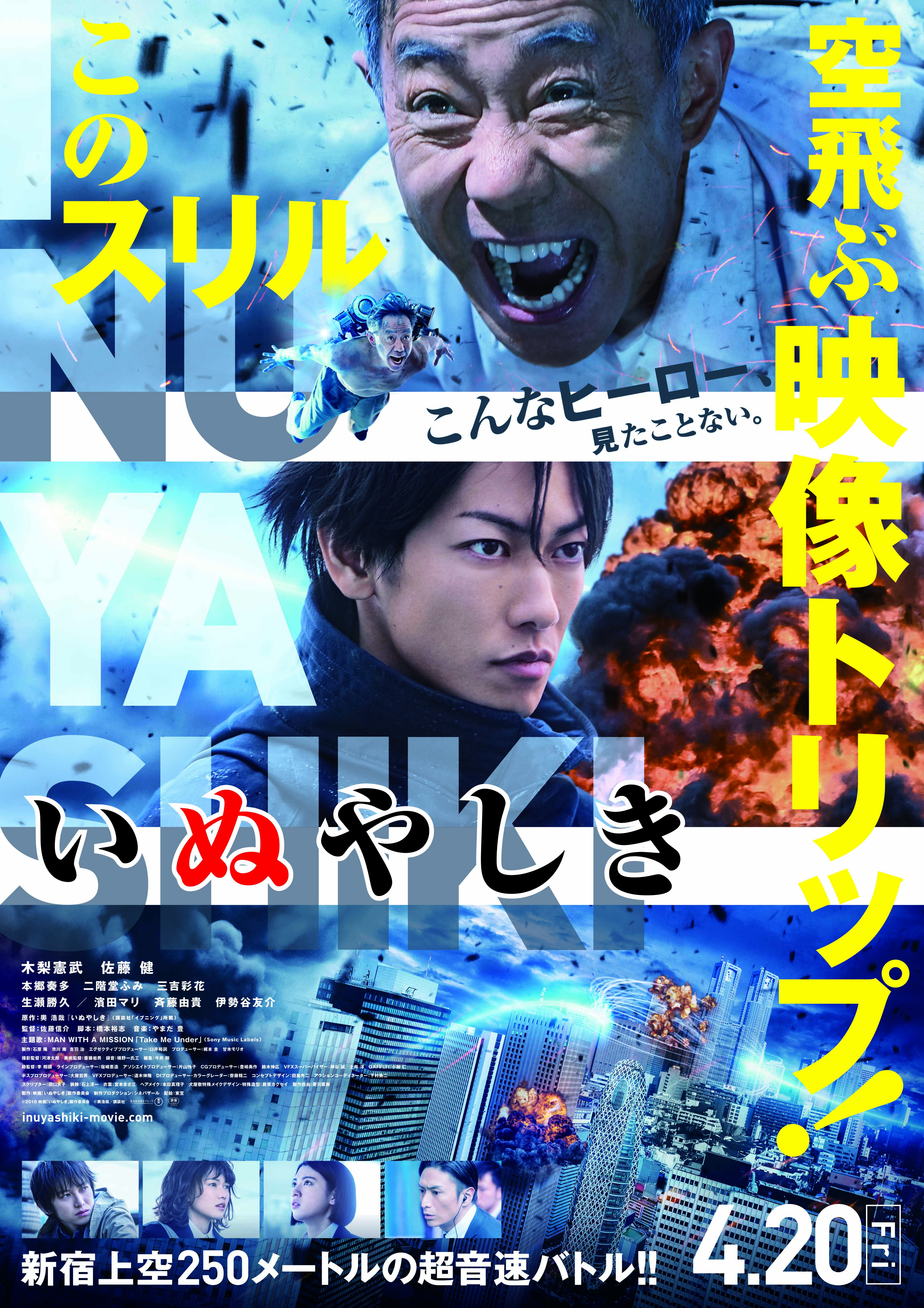

Tsugumi Ohba and Takashi Obata’s Death Note manga has already spawned three live action films, an acclaimed TV anime, live action TV drama, musical, and various other forms of media becoming a worldwide phenomenon in the process. A return to cinema screens was therefore inevitable – Death Note: Light up the NEW World (デスノート Light up the NEW World) positions itself as the first in a possible new strand of the ongoing franchise, casting its net wider to embrace a new, global world. Directed by Shinsuke Sato – one of the foremost blockbuster directors in Japan responsible for Gantz,

Tsugumi Ohba and Takashi Obata’s Death Note manga has already spawned three live action films, an acclaimed TV anime, live action TV drama, musical, and various other forms of media becoming a worldwide phenomenon in the process. A return to cinema screens was therefore inevitable – Death Note: Light up the NEW World (デスノート Light up the NEW World) positions itself as the first in a possible new strand of the ongoing franchise, casting its net wider to embrace a new, global world. Directed by Shinsuke Sato – one of the foremost blockbuster directors in Japan responsible for Gantz,

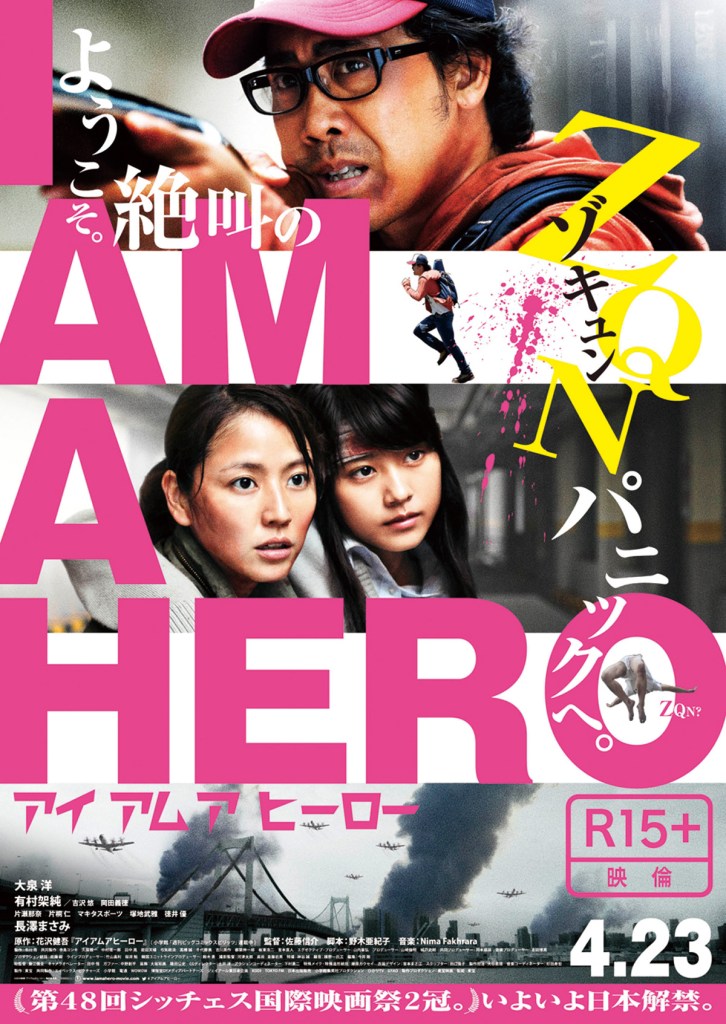

Japan has never quite got the zombie movie. That’s not to say they haven’t tried, from the arty Miss Zombie to the splatter leaning exploitation fare of Helldriver, zombies have never been far from the scene even if they looked and behaved a littler differently than their American cousins. Shinsuke Sato’s adaptation of Kengo Hanazawa’s manga I Am a Hero (アイアムアヒーロー) is unapologetically married to the Romero universe even if filtered through 28 Days Later and, perhaps more importantly, Shaun of the Dead. These “ZQN” jerk and scuttle like the monsters you always feared were in the darkness, but as much as the undead threat lingers with outstretched hands of dread, Sato mines the situation for all the humour on offer creating that rarest of beasts – a horror comedy that’s both scary and funny but crucially also weighty enough to prove emotionally effective.

Japan has never quite got the zombie movie. That’s not to say they haven’t tried, from the arty Miss Zombie to the splatter leaning exploitation fare of Helldriver, zombies have never been far from the scene even if they looked and behaved a littler differently than their American cousins. Shinsuke Sato’s adaptation of Kengo Hanazawa’s manga I Am a Hero (アイアムアヒーロー) is unapologetically married to the Romero universe even if filtered through 28 Days Later and, perhaps more importantly, Shaun of the Dead. These “ZQN” jerk and scuttle like the monsters you always feared were in the darkness, but as much as the undead threat lingers with outstretched hands of dread, Sato mines the situation for all the humour on offer creating that rarest of beasts – a horror comedy that’s both scary and funny but crucially also weighty enough to prove emotionally effective. When

When  You know how it is, you’ve left college and got yourself a pretty good job (that you don’t like very much but it pays the bills) and even a steady girlfriend too (not sure if you like her that much either) but somehow everything starts to feel vaguely dissatisfying. This is where we find Kenji (Ryo Kase) at the beginning of Isao Yukisada’s sewing bee of a movie, Rock ’n’ Roll Mishin (ロックンロールミシン). However, this is not exactly the story of a salaryman risking all and becoming a great artist so much as a man taking a brief bohemian holiday from a humdrum everyday existence.

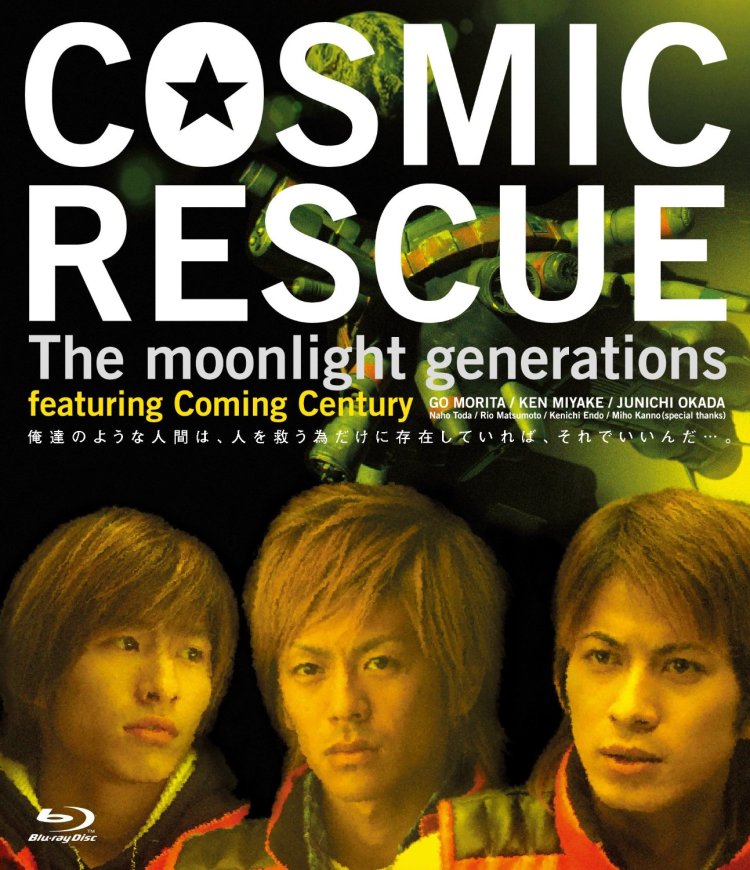

You know how it is, you’ve left college and got yourself a pretty good job (that you don’t like very much but it pays the bills) and even a steady girlfriend too (not sure if you like her that much either) but somehow everything starts to feel vaguely dissatisfying. This is where we find Kenji (Ryo Kase) at the beginning of Isao Yukisada’s sewing bee of a movie, Rock ’n’ Roll Mishin (ロックンロールミシン). However, this is not exactly the story of a salaryman risking all and becoming a great artist so much as a man taking a brief bohemian holiday from a humdrum everyday existence. It’s often posited that Japan rarely produces “science fiction” literature or movies and some say that’s because, well, they already live there. However, this isn’t quite true, there are just as many science fiction themed projects to be found in Japan as elsewhere you just have to look a little harder to find them. Depending on your point view, if you succeed in tracking down a copy of Cosmic Rescue -The moonlight generations- (コスミック・レスキュー ザ・ムーンライト・ジェネレーションズ), you may feel the quest was not entirely worth the effort.

It’s often posited that Japan rarely produces “science fiction” literature or movies and some say that’s because, well, they already live there. However, this isn’t quite true, there are just as many science fiction themed projects to be found in Japan as elsewhere you just have to look a little harder to find them. Depending on your point view, if you succeed in tracking down a copy of Cosmic Rescue -The moonlight generations- (コスミック・レスキュー ザ・ムーンライト・ジェネレーションズ), you may feel the quest was not entirely worth the effort.