Among the many parallels that could be drawn between the Meiji Restoration and the immediate post-war period, the most obvious is that each provided a clear opportunity for social change along with a moment of frozen introspection and internal debate about what the new promised future ought to look like. Following Victory of Women and The Love of the Actress Sumako, Kenji Mizoguchi completed a loose trilogy of films dealing with the theme of female emancipation with My Love Has Been Burning (わが恋は燃えぬ, Waga Koi wa Moenu), returning once again to the broken promises of Meiji as its heroine discovers that old ideas don’t change so quickly and even those who claim to be better will often disappoint.

Among the many parallels that could be drawn between the Meiji Restoration and the immediate post-war period, the most obvious is that each provided a clear opportunity for social change along with a moment of frozen introspection and internal debate about what the new promised future ought to look like. Following Victory of Women and The Love of the Actress Sumako, Kenji Mizoguchi completed a loose trilogy of films dealing with the theme of female emancipation with My Love Has Been Burning (わが恋は燃えぬ, Waga Koi wa Moenu), returning once again to the broken promises of Meiji as its heroine discovers that old ideas don’t change so quickly and even those who claim to be better will often disappoint.

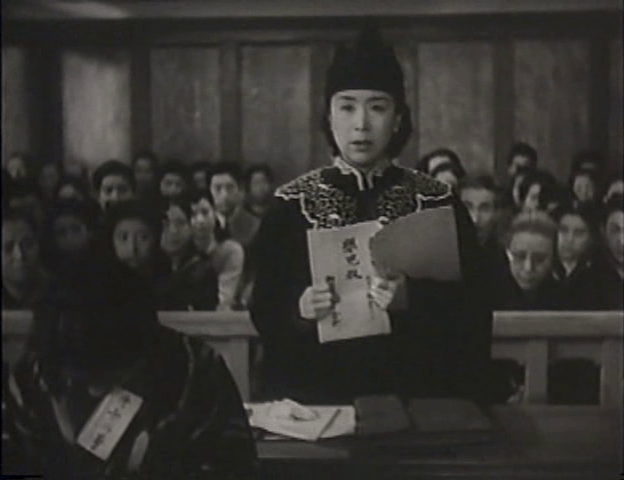

The film opens in the early 1880s as a teenage Eiko Hirayama (Kinuyo Tanaka) attends a rally to celebrate the arrival of noted feminist Toshiko Kishida (Kuniko Miyake). Eiko, a committed social liberal from a conservative middle-class family, went to see her idol in the company of a childhood friend, Hayase (Eitaro Ozawa), who is shortly going to Tokyo to study and join the democratic revolution. He halfheartedly asks Eiko to come with him, but knows that she won’t because her parents will refuse permission and she will not disobey them. Soon after, Eiko’s loyalty to her family is weakened when the family’s maid, Chiyo (Mitsuko Mito), is sold to a brothel by her father. Devastated, Eiko asks her parents for the money to buy her back but they refuse, regarding Chiyo’s sacrifice as noble and in line with filial tradition. If Chiyo had refused (not that she had the right or power to refuse), her parents would starve. Eiko rushes back to the docks, but she is too late, Chiyo and Hayase have both departed for the capital and extremely different fates.

After her family situation declines still further and Eiko decides it is impossible for her to remain under her father’s roof, she makes her own way to the city but finds it not quite so welcoming as she’d assumed it to be. Hayase is not overjoyed to see her. He merely asks if she has finally decided to marry him and becomes petulant when she reaffirms her intention to study even if she implies that she intends to marry him at a later date. During his time apart from her, Hayase has been working for the fledgling Liberal Party agitating for wider democratic rights and the expansion of the franchise, though he is irritated still further when his mentor, Omoi (Ichiro Sugai) – the leader of the socialists, is supportive of Eiko’s ambitions and agrees to find a job for her working on the party paper.

Eiko’s early disappointment in Hayase is frequently mirrored in all of her subsequent dealings with men. Hayase put on a performance of believing in her cause of women’s liberation and more widely the equality of all peoples ending centuries of feudal oppression, but really just wanted to possess her body and is unwilling to accept her decision to reject him or to choose someone else. Later visiting her after she has been imprisoned on a somewhat trumped up charge, Hayase tells her that a woman is only a woman when loved by a man, and that a woman’s fulfilment is achieved through home, family, and motherhood. He tells her that he admires her for her education and talent, but that she has “forgotten” that she is a woman. He will help her remember by getting her out of prison if only she consent to marry him even though he has previously attempted to rape her and is now working for the rightwing government having betrayed the socialist cause.

Meanwhile, Omoi looks an awful lot better. He is, ostensibly, entirely committed to socialist aims, energetically engaged in promoting the Liberal Party, and trying to ensure true democracy takes root in the new Japan, lifting the common man above his subjugated position in the still prevalent feudal hierarchy. Nevertheless, he too eventually falls in love with Eiko and like Hayase is ultimately more interested in her body than their shared cause for liberal freedom. He appears to support her desire for women’s rights as an integral part of his desire to end feudal oppressions but his belief in female equality is later exposed as superficial. Eiko, reuniting with Chiyo in prison, takes her into the household she now shares with Omoi (though they are obviously not legally married) as her maid which is perhaps not entirely egalitarian but still a well intentioned attempt to free her from the life her father condemned her to.

Omoi disappoints, bedding Chiyo while Eiko is working hard at the campaign office. Confronted, he rolls his eyes and offers a boys will be boys justification before affirming that it was just a matter of sexual satisfaction and that his feelings for her haven’t changed, mildly reproving Eiko for allowing her emotional jealously to cloud her judgement in restricting his sexual freedom. If it were indeed a matter of free love, perhaps Eiko could have understood, but Omoi damns himself when looks askance at Chiyo and remarks that it doesn’t really matter because she is nothing but a servant and a concubine. All at once, Eiko sees – despite his fine talk, Omoi may have abandoned feudal ways of thinking when it comes to working men but still sees women in terms of things. If he thinks female “servants” are not worthy of respect or agency, then what is it that he has been fighting for in his supposed mission to end oppression in Japan?

Attempting to comfort a distraught Chiyo who has been so thoroughly brainwashed that she never quite expected anything “better” than being a concubine and has truly fallen for all Omoi’s pretty words about wanting to make her happy, Eiko reminds her that as long as men continue to think as Omoi does women will never be free. Freedom and equality are what will enable female happiness, and long as men refuse to recognise women not as domestic tools but as fellow human beings there can be no freedom in Japan. Mizoguchi reinforces the idea that while one is oppressed none of us is free, neatly celebrating the success of the disappointing Omoi while lamenting that his intentions for reform will not go far enough. Eiko cannot free the women of Japan on her own, but her solution is warm and committed – she will teach them to free themselves by starting a school, educating the next generation to be better than the last. Chiyo, notably, whom she never blames or rejects, will become her first pupil neatly subverting Hayase’s cruel words when she asks Eiko to teach her how to be a woman.

Unusually brutal, My Love Has Been Burning does not shy away from the violence, often sexual violence, which both women suffer both at the hands of men and of the state as they attempt to do nothing more than live freely as full human beings. It also makes plain that even those with supposedly high ideals can disappoint as they nevertheless motion towards real social good without fully committing to its entireties. A committed pro-democratic, intensely feminist statement, Mizoguchi’s lasting message lies in an affirmation of female solidarity as, unlike the self-serving Omoi, Eiko lifts her pupil up onto her own level and draws her shawl around them both committed to proceeding forward together into a fairer future.

Female suffering in an oppressive society had always been at the forefront of Mizoguchi’s filmmaking even if he, like many of his contemporaries, found his aims frustrated by the increasingly censorious militarist regime. In some senses, the early days of occupation may not have been much better as one form of propaganda was essentially substituted for another if one that most would find more palatable. The first of his “women’s liberation trilogy”, Victory of Women (女性の勝利,

Female suffering in an oppressive society had always been at the forefront of Mizoguchi’s filmmaking even if he, like many of his contemporaries, found his aims frustrated by the increasingly censorious militarist regime. In some senses, the early days of occupation may not have been much better as one form of propaganda was essentially substituted for another if one that most would find more palatable. The first of his “women’s liberation trilogy”, Victory of Women (女性の勝利,