Junichiro Tanizaki is giant of Japanese literature whose work has often been adapted for the screen with Manji alone receiving four different filmic treatments between 1964 and 2006. His often erotic themes tallied nicely with those of the director of the 1964 version, Yasuzo Masumura who also adapted Tanizaki’s The Tattooist under the title of Irezumi, both of which starred Masumura’s muse Ayako Wakao. Preceding both of these, Keigo Kimura’s Diary of a Mad Old Man (瘋癲老人日記, Futen Rojin Nikki) adapts a late, and at that time extremely recent, work by Tanizaki which again drew some inspiration from his own life as it explores the frustrated sexuality of an older man facing partial paralysis following a stroke. Once again employing Wakao as a genial femme fatale, Kimura’s film is a broadly comic tale of an old man’s folly, neatly undercutting its darker themes with naturalistic humour and late life melancholy.

Junichiro Tanizaki is giant of Japanese literature whose work has often been adapted for the screen with Manji alone receiving four different filmic treatments between 1964 and 2006. His often erotic themes tallied nicely with those of the director of the 1964 version, Yasuzo Masumura who also adapted Tanizaki’s The Tattooist under the title of Irezumi, both of which starred Masumura’s muse Ayako Wakao. Preceding both of these, Keigo Kimura’s Diary of a Mad Old Man (瘋癲老人日記, Futen Rojin Nikki) adapts a late, and at that time extremely recent, work by Tanizaki which again drew some inspiration from his own life as it explores the frustrated sexuality of an older man facing partial paralysis following a stroke. Once again employing Wakao as a genial femme fatale, Kimura’s film is a broadly comic tale of an old man’s folly, neatly undercutting its darker themes with naturalistic humour and late life melancholy.

Tanazaki’s stand in is a wealthy old man, Utsugi (So Yamamura), who has recently suffered a stroke which has paralysed his right hand and significantly reduced his quality of life. He currently operates a large household with a number of live-in staff, including a round the clock nurse, his wife, son, daughter-in-law, and grandson. The son, Joukichi (Keizo Kawasaki), is a successful executive currently having an affair with a cabaret dancer, leaving his extremely beautiful wife, Sachiko (Ayako Wakao), herself also formerly a dancer, at a loose end. Though approaching the end of his life and possibly physically incapable of acting on his desire, Utsugi is consumed with lust for Sachiko and thinks of little else but how to convince her to allow him even the smallest of intimacies. Sachiko, for her part, is not particularly interested in pursuing a romantic entanglement with her aged father-in-law but is perfectly aware of her power over him which she uses to fulfil her material desires. Meanwhile, Utsugi’s rather pathetic behaviour has not gone unnoticed by the rest of the household who view his desperation with a mix of pity, exasperation, and outrage.

Kimura’s film takes more of an objective view than the subjective quality of the title would suggest but still treats its protagonist with a degree of well intentioned sympathy for a man realising he’s reached the final stages of his life. Utsugi’s sexual desire intensifies even as his body betrays him but this very life force becomes his rebellion against the encroaching onset of decay as he clings to his virility, trying to off-set the inevitable. As such, conquest of Sachiko becomes his last dying quest for which he is willing to sacrifice anything, undergo any kind of degradation, simply to climb one rung on the ladder towards an eventual consummation of his desires.

Sachiko, instinctively disliked by her mother-in-law, is more than a match for Utsugi’s finagling. A young, confident, and beautiful woman, Sachiko has learned how to do as she pleases without needing permission from anyone for anything. In this, the pair are alike – both completely self aware yet also in full knowledge of those around them. The strange arrangement they’ve developed is a game of reciprocal gift giving which is less a war than a playful exercise in which both are perfectly aware of the rules and outcomes. Sachiko allows Utsugi certain privileges beginning with slightly patronising flirtation leading to leaving the bathroom door unlocked when she showers (behind a curtain) and permitting Utsugi to kiss and fondle her leg (even if she hoses it down, complaining it feels like being licked by a slug).

Tanizaki’s strange fetish is again in evidence as Utsugi finally deifies Sachiko in creating a print of the sole of her foot which he intends to have carved into his grave so he can live protected beneath her forever, as insects are under the foot of Buddha. This final act which takes the place of a literal consummation goes some way towards easing his desire but may also be the one which pushes him towards the grave he was seeking to avoid. Notably, Sachiko is bored and eventually exhausted by the entire enterprise even whilst Utsugi is caught in the throws of his dangerous ecstasy.

Other members of the household view the continuing interaction of Sachiko and Utsugi with bemusement, pitying and resenting the old man for his foolishness whilst half-admiring, half disapproving of Sachiko’s manipulation of his desires. Utsugi had been a stingy man despite his wealth and even now risks discord within his own family by refusing to assist his grown-up daughter who finds herself in financial difficulty and in need of familial support, yet lavishing vast sums on Sachiko for expensive trinkets even as she continues an affair with a younger man right under his nose. Still, Sachiko uses what she has and gets what she wants and Utsugi attempts to do the same only less successfully, completely self aware of his foolishness and the low probability of success yet buoyed with each tiny concession Sachiko affords him. A wry and unforgiving exploration of the link between sex and death, Diary of a Mad Old Man undercuts the less savoury elements of its source material with a broadly humorous, mocking tone gradually giving way to melancholy as the old man begins to accept his own impotence, the light around him dwindling while Sachiko’s only brightens.

Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency.

Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency. Now four instalments into the Lone Wolf and Cub series, Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) have been on the road for quite some time, seeking vengeance against the Yagyu clan who framed Ogami for treason, murdered his wife, and stole his prized position as the official Shogun executioner. Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in Peril (子連れ狼 親の心子の心, Kozure Okami: Oya no Kokoro Ko no Kokoro) is the first in the series not to be directed by Kenji Misumi (though he would return for the following chapter) and the change in approach is very much in evidence as veteran Nikkatsu director Buichi Saito picks up the reins and takes things in a much more active, full on ‘70s exploitation direction. Where

Now four instalments into the Lone Wolf and Cub series, Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) have been on the road for quite some time, seeking vengeance against the Yagyu clan who framed Ogami for treason, murdered his wife, and stole his prized position as the official Shogun executioner. Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in Peril (子連れ狼 親の心子の心, Kozure Okami: Oya no Kokoro Ko no Kokoro) is the first in the series not to be directed by Kenji Misumi (though he would return for the following chapter) and the change in approach is very much in evidence as veteran Nikkatsu director Buichi Saito picks up the reins and takes things in a much more active, full on ‘70s exploitation direction. Where

Another vehicle for post-war singing star Hibari Misora, With a Song in her Heart (希望の乙女, Kibo no Otome) was created in celebration of the tenth anniversary of her showbiz debut. As such, it has a much higher song to drama ratio than some of her other efforts and mixes fantasy production numbers with band scenes as Hibari takes centre stage playing a young woman from the country who comes to the city in the hopes of becoming a singing star.

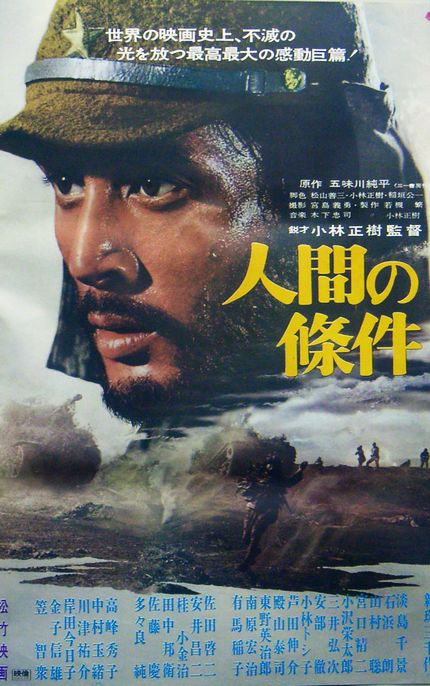

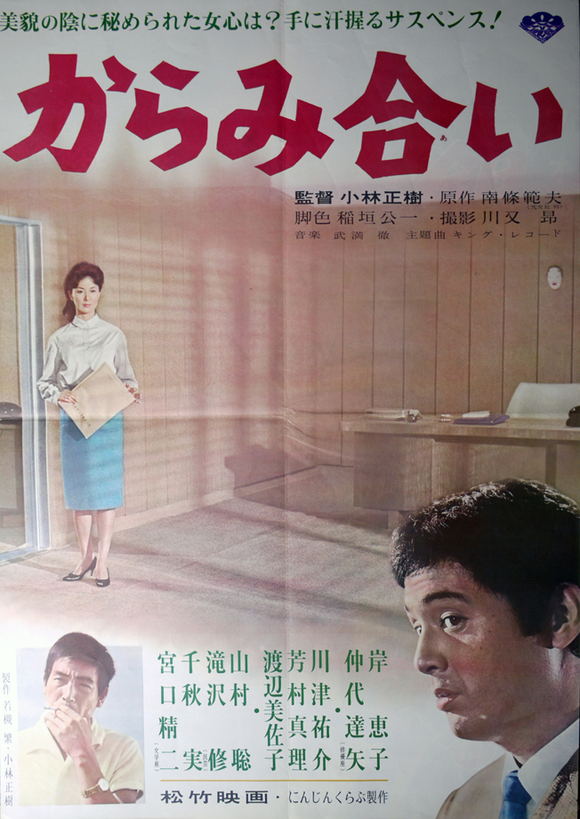

Another vehicle for post-war singing star Hibari Misora, With a Song in her Heart (希望の乙女, Kibo no Otome) was created in celebration of the tenth anniversary of her showbiz debut. As such, it has a much higher song to drama ratio than some of her other efforts and mixes fantasy production numbers with band scenes as Hibari takes centre stage playing a young woman from the country who comes to the city in the hopes of becoming a singing star. Kobayashi’s first film after completing his magnum opus, The Human Condition trilogy, The Inheritance (からみ合い, Karami-ai) returns him to contemporary Japan where, once again, he finds only greed and betrayal. With all the trappings of a noir thriller mixed with a middle class melodrama of unhappy marriages and wasted lives, The Inheritance is yet another exposé of the futility of lusting after material wealth.

Kobayashi’s first film after completing his magnum opus, The Human Condition trilogy, The Inheritance (からみ合い, Karami-ai) returns him to contemporary Japan where, once again, he finds only greed and betrayal. With all the trappings of a noir thriller mixed with a middle class melodrama of unhappy marriages and wasted lives, The Inheritance is yet another exposé of the futility of lusting after material wealth.