Review of the first of the two part live action Attack on Titan (進撃の巨人 ATTACK ON TITAN, Shingeki no Kyojin) extravaganza first published by UK Anime Network.

Review of the first of the two part live action Attack on Titan (進撃の巨人 ATTACK ON TITAN, Shingeki no Kyojin) extravaganza first published by UK Anime Network.

It is a law universally acknowledged that a successful manga must be in want of an anime adaptation. Once this simple aim has been achieved, that same franchise sets its sights on the even loftier goals of the live action movie. This phenomenon is not a new one and has frequently had extremely varied results but fans of the current cross over phenomenon that is Attack on Titan may find themselves wondering if perhaps more time should have been allowed before this much loved series tried its luck in the non animated world.

Throwing in a few changes from the source material, the film begins with the peaceful and prosperous walled city where childhood friends Eren, Armin, and Mikasa are young adults just about to start out on the next phase of their lives. Eren, however, is something of a rebellious lost soul who finds himself gazing at the land beyond the walls rather than on a successful future in the mini city state. However, little does he know that the Titans – a race of man eating giants responsible for the destruction which saw humanity retreat behind the walls in the first place, are about to resurface and wreak havoc again. His dreams of a more exciting life may have been granted but humanity pays a heavy price.

Fans of the manga and anime may well be alarmed by certain elements of the above paragraph. Yes, the film makes slight but significant changes to its source material which may leave fans feeling confused and annoyed as the film continues to grow away from the franchise they know and love so well. For a newcomer, things aren’t much better as characterisation often relies of stereotypes and blunt exposition to get its point across. Attack on Titan actually has a comparatively starry cast with actors who’ve each impressed in other high profile projects including Haruma Miura (Eternal Zero), and Kiko Mizuhara (Norwegian Wood, Helter Skelter) as well as Kanata Hongo (Gantz) but even they can’t bring life to the stilted, melodramatic script. Things take a turn for the worse when Satomi Ishihara turns up having presumably been given the instruction to play Hans as comic relief only with a TV style, huge and bumbling performance.

That said, there are some more interesting ideas raised – notably that even a paradise becomes a prison as soon as you put a wall around it. Indeed, everything seems to have been going pretty well inside the walls until Eren suddenly decides he finds them constraining. Once the Titans break through, the very mechanism which was put in place for humanity’s protection, the walls themselves, become the thing which damns them as they’re trapped like rats unable to escape the Titan onslaught.

Machines are now outlawed following past apocalyptic events – humanity apparently can’t be trusted not to destroy itself and this cheerful, feudal way of life is contrasted with the chaos and pollution which accompanied the technologically advanced era. Unfortunately, a reversion to distinctly old fashioned values also seems to have occurred as we’re told you need permission to get married (as sensible as this may be from a practical standpoint in a military society) and the single mother gets munched just as she’s making the moves on a potential new father for her child. The Titans themselves have also been read as a metaphor for xenophobia which isn’t helped by the almost fascist connotations of the post attack society.

Much of this is really overthinking what appears to be an intentionally silly B-movie about man eating giants running amok in a steampunk influenced post-apocalyptic society but then it does leave you with altogether too much time to do your thinking while you’re waiting for things to happen. The original advent of the Titans is a little overplayed with the deliberately gory chomping continuing far too long. Action scenes fare a little better but suffer from the poor CGI which plagues the rest of the film. This isn’t the Attack on Titan movie you were expecting. This is a monster movie which carries some extremely troubling messages, if you stop to think about them. The best advice would be to refuse to think at all and simply settle back for some kaiju style action but fans of either campy monster movies or any other Attack on Titan incarnation are likely to come away equally disappointed. It only remains to see if Part 2 of this bifurcated tale can finally heal some of the many holes in this particularly weak wall.

US release trailer:

Hibari Misora was one of the leading lights of the post-war entertainment world. Largely active as a chart topping ballad singer, she also made frequent forays into the movies notably starring with fellow musical stars Izumi Yukimura and Chiemi Eri in the

Hibari Misora was one of the leading lights of the post-war entertainment world. Largely active as a chart topping ballad singer, she also made frequent forays into the movies notably starring with fellow musical stars Izumi Yukimura and Chiemi Eri in the  In old yakuza lore, the “ninkyo” way, the outlaw stands as guardian to the people. Defend the weak, crush the strong. Of course, these are just words and in truth most yakuza’s aims are focussed in quite a different direction and no longer extend to protecting the peasantry from bandits or overbearing feudal lords (quite the reverse, in fact). However, some idealistic young men nevertheless end up joining the yakuza ranks in the mistaken belief that they’re somehow going to be able to help people, however wrongheaded and naive that might be.

In old yakuza lore, the “ninkyo” way, the outlaw stands as guardian to the people. Defend the weak, crush the strong. Of course, these are just words and in truth most yakuza’s aims are focussed in quite a different direction and no longer extend to protecting the peasantry from bandits or overbearing feudal lords (quite the reverse, in fact). However, some idealistic young men nevertheless end up joining the yakuza ranks in the mistaken belief that they’re somehow going to be able to help people, however wrongheaded and naive that might be. Review the concluding chapter of Takashi Yamazaki’s Parasyte live action movie (寄生獣 完結編, Kiseiju Kanketsu Hen) first published by

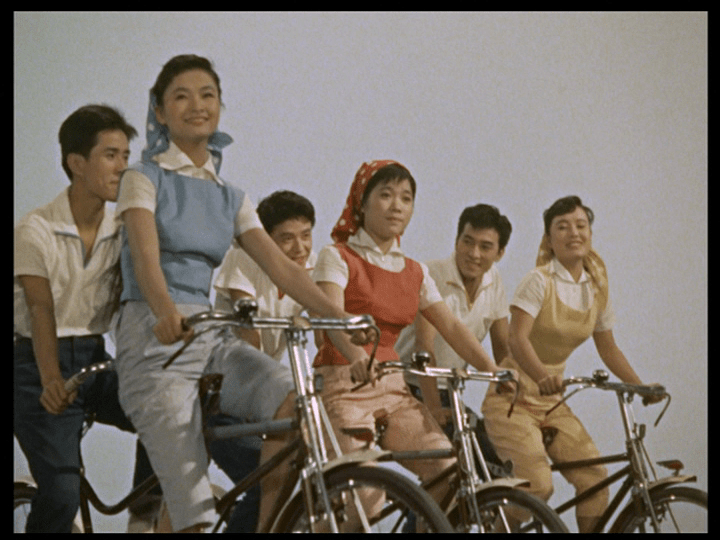

Review the concluding chapter of Takashi Yamazaki’s Parasyte live action movie (寄生獣 完結編, Kiseiju Kanketsu Hen) first published by  The Sannin Musume girls are growing up by the time we reach 1957’s On Wings of Love (大当り三色娘, Ooatari Sanshoku Musume). In fact, they each turned 20 this year (which is the age you legally become an adult in Japan), so it’s out with the school girl stuff and in with more grown up concerns, or more specifically marriage. Wings of Love is the third film to star the three Japanese singing stars Hibari Misora, Chiemi Eri, and Izumi Yukimura who come together to form the early idol combo supergroup Sannin Musume. Once again modelled on the classic Hollywood musical, On Wings of Love is the very first Tohoscope film giving the girls even more screen to fill with their by now familiar cute and colourful antics.

The Sannin Musume girls are growing up by the time we reach 1957’s On Wings of Love (大当り三色娘, Ooatari Sanshoku Musume). In fact, they each turned 20 this year (which is the age you legally become an adult in Japan), so it’s out with the school girl stuff and in with more grown up concerns, or more specifically marriage. Wings of Love is the third film to star the three Japanese singing stars Hibari Misora, Chiemi Eri, and Izumi Yukimura who come together to form the early idol combo supergroup Sannin Musume. Once again modelled on the classic Hollywood musical, On Wings of Love is the very first Tohoscope film giving the girls even more screen to fill with their by now familiar cute and colourful antics. Romantic Daughters (ロマンス娘, Romance Musume) is the second big screen outing for the singing star combo known as “sannin musume”. A year on from

Romantic Daughters (ロマンス娘, Romance Musume) is the second big screen outing for the singing star combo known as “sannin musume”. A year on from  Pop stars invading the cinematic realm either for reasons of commerce, vanity, or just simple ambition is hardly a new phenomenon and even continues today with the biggest singers of the era getting to play their own track over the closing credits of the latest tentpole feature. This is even more popular in Japan where idol culture dominates the entertainment world and boy bands boys are often top of the list for any going blockbuster (wisely or otherwise). Cycling back to 1955 when the phenomenon was at its heyday all over the world, So Young, So Bright (ジャンケン娘, Janken Musume) is the first of four so called “three girl” (Sannin Musume) musicals which united the three biggest female singers of the post-war era: Hibari Misora, Chiemi Eri, and Izumi Yukimura for a music infused comedy caper.

Pop stars invading the cinematic realm either for reasons of commerce, vanity, or just simple ambition is hardly a new phenomenon and even continues today with the biggest singers of the era getting to play their own track over the closing credits of the latest tentpole feature. This is even more popular in Japan where idol culture dominates the entertainment world and boy bands boys are often top of the list for any going blockbuster (wisely or otherwise). Cycling back to 1955 when the phenomenon was at its heyday all over the world, So Young, So Bright (ジャンケン娘, Janken Musume) is the first of four so called “three girl” (Sannin Musume) musicals which united the three biggest female singers of the post-war era: Hibari Misora, Chiemi Eri, and Izumi Yukimura for a music infused comedy caper. Kon Ichikawa may be best remembered for his mid career work, particularly his war films The Burmese Harp and

Kon Ichikawa may be best remembered for his mid career work, particularly his war films The Burmese Harp and  Generally speaking, where a film has been inspired by already existing source material, it’s unfair to refer to it as a “remake” even if there has been an iconic previous adaptation. That said, in the case of Tsubaki Sanjuro (椿三十郎), “remake” is very much at the heart of the idea as the film uses the exact same script as the massively influential 1962 version directed by Akira Kurosawa which also starred his muse Toshiro Mifune. Director Yoshimitsu Morita is less interested in returning to the story’s novelistic roots than he is in engaging with Kurosawa’s cinematic legacy.

Generally speaking, where a film has been inspired by already existing source material, it’s unfair to refer to it as a “remake” even if there has been an iconic previous adaptation. That said, in the case of Tsubaki Sanjuro (椿三十郎), “remake” is very much at the heart of the idea as the film uses the exact same script as the massively influential 1962 version directed by Akira Kurosawa which also starred his muse Toshiro Mifune. Director Yoshimitsu Morita is less interested in returning to the story’s novelistic roots than he is in engaging with Kurosawa’s cinematic legacy. When a crime has been committed, it’s important to remember that there may be secondary victims whose lives will be destroyed even if they themselves had no direct involvement in the case itself. This is even more true in the tragic case that person who is responsible is themselves a child with parents and siblings still intent on looking forward to a life that their son or daughter will now never lead. This isn’t to place them on the same level as bereaved relatives, but simply to point out the killer’s family have also lost a child who they have every right to grieve for, though their grief will also be tinged with guilt and shame.

When a crime has been committed, it’s important to remember that there may be secondary victims whose lives will be destroyed even if they themselves had no direct involvement in the case itself. This is even more true in the tragic case that person who is responsible is themselves a child with parents and siblings still intent on looking forward to a life that their son or daughter will now never lead. This isn’t to place them on the same level as bereaved relatives, but simply to point out the killer’s family have also lost a child who they have every right to grieve for, though their grief will also be tinged with guilt and shame.