A former mercenary’s bid for revenge having failed in his responsibilities soon goes awry in Wong Jing’s third directorial feature Mercenaries from Hong Kong (獵魔者). As is constantly pointed out to the hero, perhaps he’s not so different from his target with his very selective brand of justice and morality. After all maybe the difference between medicine smuggler and drug trafficker is largely semantic and taking revenge after the fact hardly makes up for the failure to protect the innocent from a world you’ve helped create.

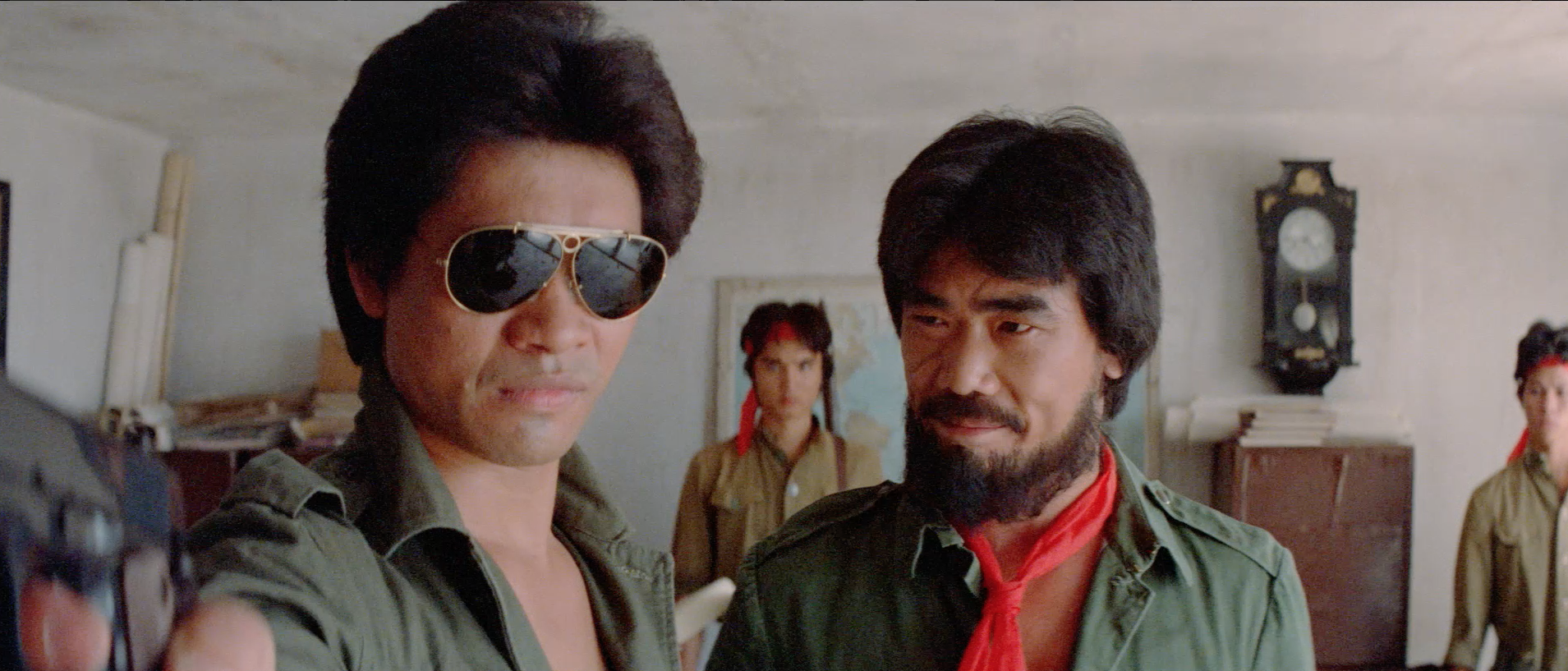

Li Lok (Ti Lung) is a pretty big figure on the underworld scene and as the ultra macho title sequence reveals a former mercenary who served in Vietnam. In the daring opening scene he sneaks into a gang hideout disguised as a telephone repairman and takes out a gangster in the middle of drugging a young woman whom he and his friend intend to rape and then murder. But Li Lok isn’t here to save the girl and in fact he doesn’t. He’s there because the gangster has done this kind of thing before and the previous victim was his 15-year-old niece whose care he had been entrusted with by his late brother before he passed away. Later one of his comrades will make a similar request of him and he will fail again apparently taking little stock of his responsibilities.

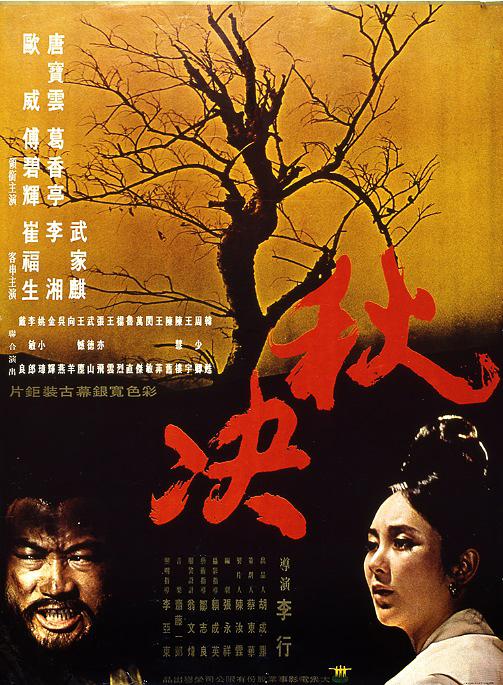

Nevertheless, having knocked off the gangster annoys local big boss Shen who intends to have Li Lok eliminated but Hong Kong’s richest woman Ho Ying (Candice Yu On-On) convinces him not to because she has a job for Lok assassinating a top Thai assassin who killed her father and is now apparently blackmailing her with a cassette tape full of corporate secrets. All Lok needs to do is round up a posse and head to Cambodia where “the devil” Naiman (Ching Miao) is hiding out, kidnap him, and retrieve the tape to receive a massive life-changing payout while permanently getting Shen off his back. It all sounds like a pretty good deal to Lok along with the former buddies he recruits to join him who are all trapped in desperate poverty one with a sick little girl who desperately needs a kidney transplant.

This is a Wong Jing film and perhaps there’s no need to dig too deeply into it, but there is something in the power Ying wields over Lok and his team by virtue of her wealth and privilege that speaks to the city’s growing inequality though it’s also true that perhaps the guys have all fallen low through their mercenary choices and are now unable to get a foothold in the contemporary society without resorting to crime. Yet perversely, Ying leverages Lok’s chivalrous sense of honour as part of her plan playing damsel in distress rather than dangerous femme fatale while he assumes he’s on a righteous mission planning to turn Naiman over to the authorities rather than just killing him while little caring that his actions threaten to destabilise an already chaotic situation in Cambodia.

When one of the sworn brothers of the gangster that Lok killed in revenge is killed coming after him even after the truce, Lok is irritated that he died unnecessarily as if it offends his sense of justice that this man was not protected better by Shen. Yet as Naiman keeps pointing out to him, he’s no saint and perhaps no different. He could have saved the girl in the gang hideout but chose not to, escaping by jumping out of a window onto a van waiting below and riding off on a motorcycle (which is admittedly impressive). He claims to hate drug dealers but profited off war and misery in smuggling medicines across the border from Thailand into Cambodia even if he could tell himself he was running a kind of humanitarian service. Meanwhile Ying who is obviously involved in something shady if she’s dealing with people like Lok and his team, paying for their weapons and equipment which presumably includes the series of identical outfits the guys sport like some violent middle-aged boy band, wins an Outstanding Woman award and ironically pledges to use some of her wealth to fund community-based anti-drug programs.

Li Lok may in a sense emerge victorious but also exactly where he started in failing to protect an innocent girl from a mercenary world. The Cantonese title might more literally be something like Devil Hunters, but Lok and his guys are certainly a mercenary bunch desperate to escape their poverty and hopelessness even if they may stand for a kind of justice and honour in brotherhood. This being a Wong Jing film there is plenty of crass humour including some that is very of its time along with gratuitous sex and female nudity but also a series of incredibly impressive action scenes and a bleaker than bleak conclusion which may suggest that the Loks of the world will be unable to protect the next generation from the violence they themselves have unleashed.

Mercenaries from Hong Kong screened as part of this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)