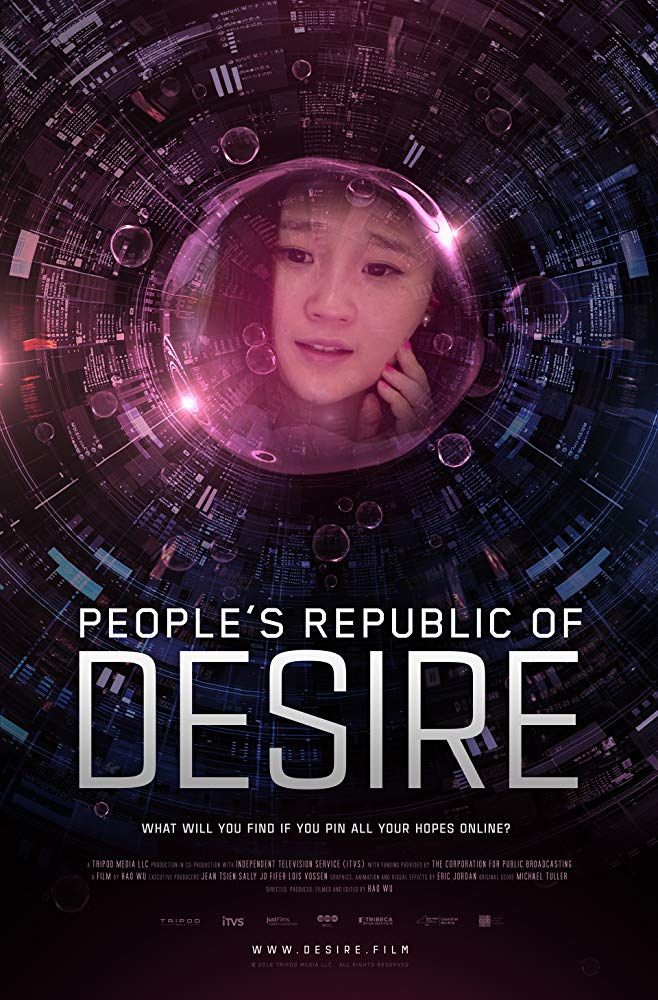

Can you outsource a dream? According to Wu Hao’s People’s Republic of Desire (欲望共和国, Yùwàng gònghéguó), many in modern China have resigned themselves to doing just that. Feeling lonely, disconnected, hopeless, they turn to people just like them who’ve been luckier and have not yet decided to give up the fight. Video streaming service YY acts like the future’s version of pirate radio, lining up a selection “personalities” male and female offering pretty much anything from stand up comedy and political diatribes to off key singing and a window into someone else’s every day life from breakfast to dinner. Of course, it all comes at a price – one which YY gleefully takes a 60% cut of, but there are hidden costs too – to a society, to the deluded fans, and even to the aspiring stars themselves forced into various debasing acts in the knowledge that their time in the spotlight will soon come to an end.

Can you outsource a dream? According to Wu Hao’s People’s Republic of Desire (欲望共和国, Yùwàng gònghéguó), many in modern China have resigned themselves to doing just that. Feeling lonely, disconnected, hopeless, they turn to people just like them who’ve been luckier and have not yet decided to give up the fight. Video streaming service YY acts like the future’s version of pirate radio, lining up a selection “personalities” male and female offering pretty much anything from stand up comedy and political diatribes to off key singing and a window into someone else’s every day life from breakfast to dinner. Of course, it all comes at a price – one which YY gleefully takes a 60% cut of, but there are hidden costs too – to a society, to the deluded fans, and even to the aspiring stars themselves forced into various debasing acts in the knowledge that their time in the spotlight will soon come to an end.

Wu follows two very different YY stars – 21-year-old former nurse Shen Man, and Big Li – a former migrant worker whose rough voice and man’s man attitudes have endeared him to a host of other “diaosi” fans. “Diaosi”, once an unpleasant slur meaning “loser” and most often applied to those stuck in the lower orders of China’s rapidly increasing social equality gap, has been reclaimed by those who self identify with its sense of ironic hopelessness. As Shen Man explains, YY works as a kind of pyramid system in which millions of dreaming diaosi throw money they don’t really have at online stars in the hope of connection while Tuhao – the nouveau riche looking for new ways to splash the cash, act as patrons deciding the direction of the service.

What many diaosi forget to factor in is that in reality the entire service is run by agents and promoters who push their various stars to steal “votes” from their online fans. YY is not a public service platform, but a vast money making machine which sucks in cash from every conceivable angle. As cynical patron Songge points out, those seeking fame on YY cannot expect to make any money. In order to win the site’s popularity contest, they need to get an agent and their agent will need to spend a vast amount of money to promote them which the star will then need to make back.

Shen Man, on one level naive, is perfectly aware of the way the system works. She knows she needs to keep her fans happy or they’ll leave. Like Big Li she’s a poor girl made good, a figure her female fans can look up to as someone just like them that’s been able to escape the world of diaosi drudgery. Her male fans, by contrast, are probably looking for something different. Some of them like the idea of her ordinariness, that she comes from the same place they do and is therefore attainable while also being unattainable thanks to her quickly acquired wealth which allows her to live the life of a modern princess. There is however a cost. In order to hook more fans the youthful 21-year-old has already spent a lot of money on extensive plastic surgery (perhaps veering dangerously close to destroying her “natural charm” selling point), and is expected to play nice with her sometimes insulting clientele. One patron, chatting idly on the phone, tries to throw money at her in return for sex whilst simultaneously insisting that she’s not like the other YY girls who will do anything for money. Shen Man points out that she has money already and is not that sort of girl while her patron continues along the same line of argument insisting that all you need to do get a girl is flash the cash.

Big Li, by contrast, is much less cynical. He recognises that he’s become a kind of leader for his diaosi brothers and is eager not to let his fans down. Married to YY talent manager Dabao and with a young son to take care of, Big Li is originally grateful for his rock star life, but the pressure begins to get to him and he longs for the simple days of the village filled with the warmth of family and friends rather than the lonely false connection of YY’s race to fame mentality. Big Li genuinely cares, but this is his downfall. He wants the freedom that YY promises and refuses to play the game, but the game continues to play him.

Adoration quickly to hate. Shen Man finds herself out in the cold when she is publicly slut shamed, accused of taking money from fans in return for sexual favours, earning the nickname of “300 Man” as a woman who can be brought so cheaply she has no value at all. The constant double standard – that she must be beautiful and desirable, yet pure and chaste, has something to say about the nature of China’s conservative social values even in a modernising age. Once your reputation has gone it cannot be rebuilt and even the loyalist fans will find themselves moving on. Big Li might not have to put up with the same kind of pressures as Shen Man, but is personally hurt when fans call him “scammer” because of his constant failures to take home the big prize.

So what of the fans themselves? There are those who’ve made vast amounts money thanks to China’s rapidly modernising economy and don’t know what to do with it other than show off by giving it away. They too are trying to buy connection through becoming patrons, “owning” someone less fortunate and taking pleasure in dictating their lives. Meanwhile, on the opposite end of the scale, the diaosi have all but given up on their own dreams and so “enjoy” investing money to “support” the dreams of those just like them out of a sense of frustrated solidarity.

The picture Wu paints of modern China is one of a world spiralling out of control in which intense loneliness and alienation have corrupted the nature of social connection. Money rules all. Wealth is all that matters and in the crowded online world, if you want to be noticed you’ll have to pay. Interactions are bought and paid for with petty, entirely virtual trinkets, while in the offline world all there is is work and sleep and cheap fast food. Only the platform is the winner, as one unlucky hopeful puts it. The sad truth is that everyone knows it’s a losing game and has resigned themselves to conceding defeat in a society already leaving them behind.

People’s Republic of Desire was screened as part of Fantasia International Film Festival 2018.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Montreal’s

Montreal’s