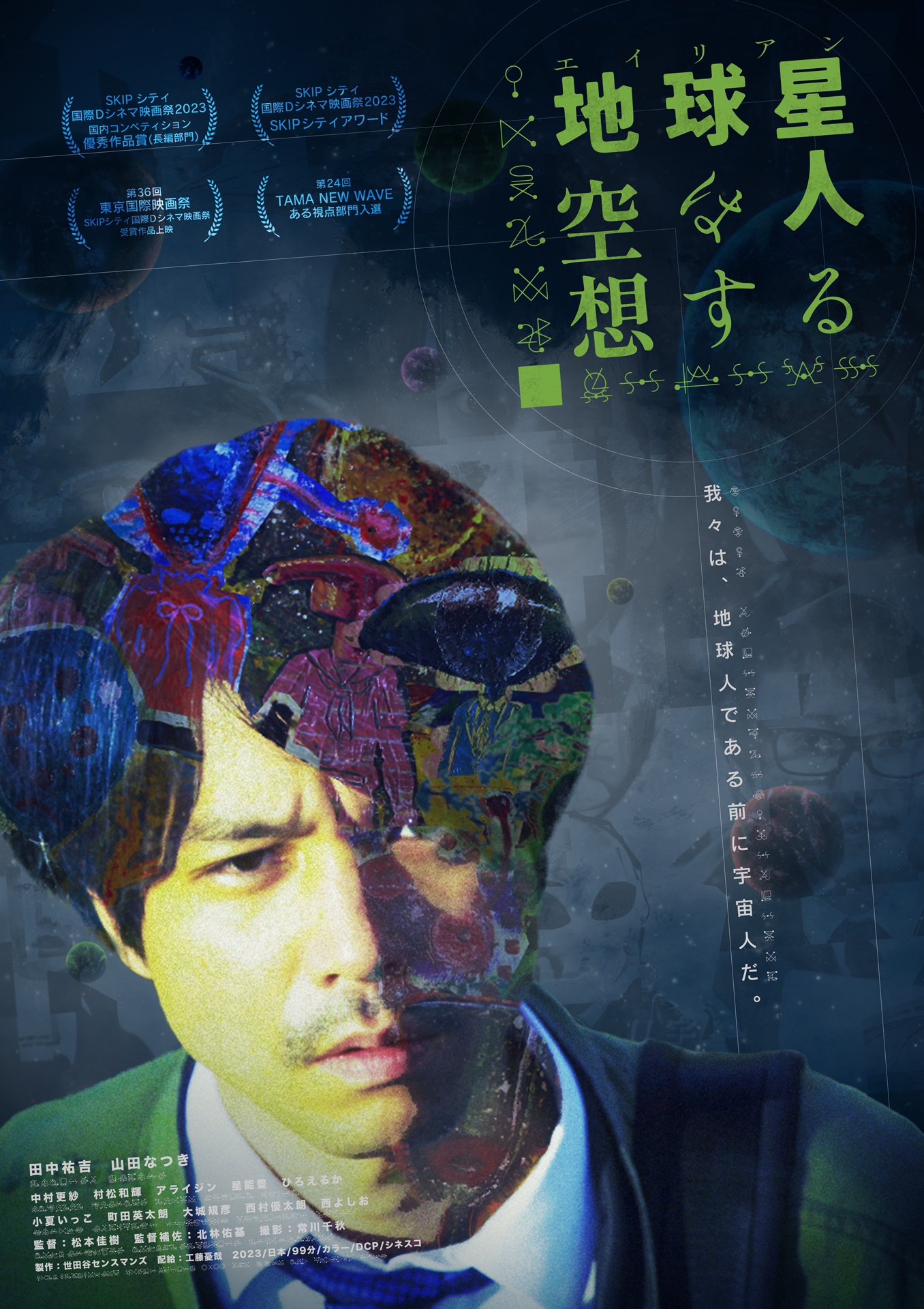

Who can really say what’s real and what’s not, who gets to decide what’s right and what’s wrong? The journalistic hero of Yoshiki Matsumoto’s Alien’s Daydream (地球星人(エイリアン)は空想する, Chikyu Seijin (Alien) wa Kusosuru) is asked each of these questions when railing against the absurdities of his latest assignment, a possible UFO hotspot in an otherwise remote area of Japan. In addition to the question of whether there is life on other planets, Ito is confronted by questions of press ethics as he begins to wonder if telling the truth is really the right thing to do.

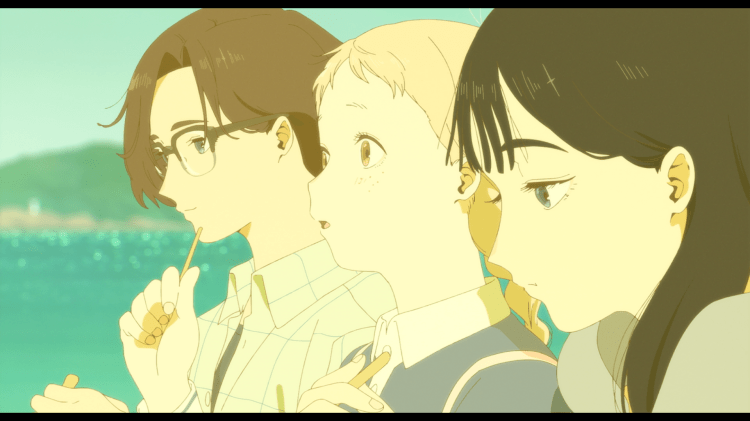

In many ways, Uto’s (Yukichi Tanaka) problem is his rigidity. He doesn’t like injustice, so he stands up to some people bullying a homeless man but then also threatens to report him to the police pointing at the no loitering sign behind him. He something similar while visiting the space museum in the UFO town, abruptly breaking off his interview to confront a young woman and ask her if she has a ticket even though it’s not his responsibility seeing as he doesn’t work there and in fact it’s none of his business. Uto likes to think of himself as a serious journalist and and wants to do real investigations into the things he thinks matter, but is employed by a sleazy tabloid mainly interested in celebrity sex scandals and bits of weird news like the UFO town.

That’s one reason Uto had little interest in going, but in the end doesn’t have much choice and is surprised to find there actually might be a story in it after all even if not quite the one his boss might be looking for. A local man is claiming to have been abducted by aliens and dumped in a random place some distance from where he was taken, while the girl he interrogated about her ticket, Noa, keeps making cryptic statements about “earthlings”, refers to aliens as her “people” and is fascinated by crop circles.

What he eventually discovers is that Noa may really have been kidnapped a few years ago if by a more terrestrial presence and subsequently brainwashed by a UFO worshipping cult. He realises that to some, including the girl’s mother, the stuff about aliens is a harmless delusion and blessing in disguise that prevents her from remembering what “really” happened. Uto want to write an article stating what how thinks it was, but if he does so there’a chance Noa may find out the “truth” and have her illusions shattered. He goes ahead and publishes anyway, but then realises his central hypothesis may have been incorrect and he’s fingered the wrong man. He then has another dilemma of whether or not to correct his article with Noa’s mother and friends each saying it’s better if he just lets it stand as the truth so that at least Noa won’t be branded a crazy cultist.

It turns out the local UFO lore has a surprisingly long history dating back to the Edo era which has given rise to a series of folk legends. The space museum itself is designed to resemble the pre-modern UFO and is a decidedly strange place where the manager is constantly shadowed by a man in a green alien mask.Yet what Uto is later learns is that we are all perhaps lonely aliens, each from different planets which is why we’re so different from each other. Uto himself often seems somehow alien in his rigidity and black of white way of thinking, a quality perfectly brought out by Yukichi Tanaka’s stiffness and often vacant stare. Noa asks him if he isn’t tire of living his life like that, so needlessly uptight and unimaginative and perhaps in a way he is though he soon turns the equation around on her. Dividing the film into 10 chapters each with a strange and childlike illustration, Matsumoto adds a touch of whimsical absurdity to what could otherwise be quite a dark tale. Uto may have to learn that he isn’t the arbiter of the truth, selling believable lies to a readership looking for something to make life more interesting, but is free to find the truth for himself because it is of course out there for those want to believe.

Alien’s Daydream screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Original trailer (no subtitles)