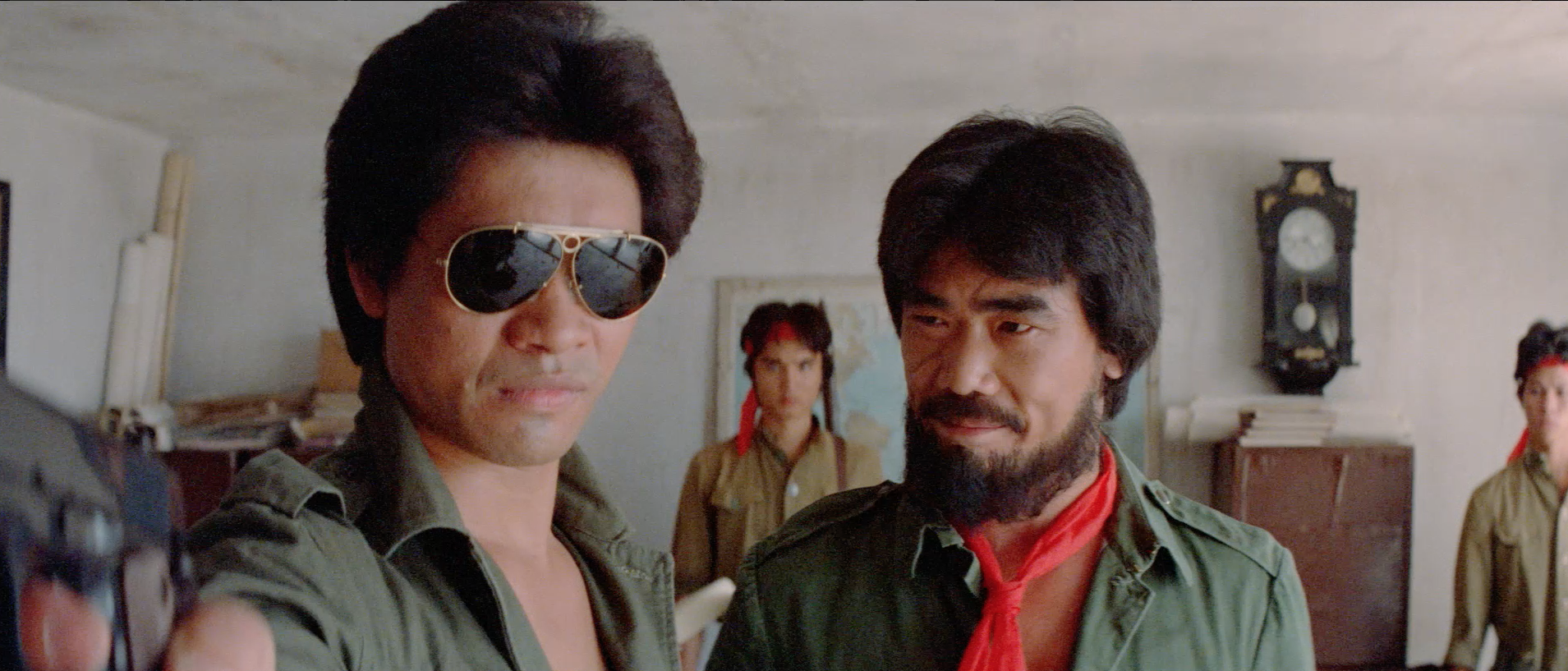

A 30-something couple find themselves pulled in different directions by their conflicting desires in Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit’s post-modern comedy, Fast & Feel Love (เร็วโหด..เหมือนโกรธเธอ). As the title implies, the self-involved hero is eventually forced to accept that his success is founded on the support of those around him while belatedly stepping in to adulthood in undergoing a baptism of fire learning basic life skills along with the confidence to look after himself in a new world of grownup responsibilities.

Jay (Urassaya Sperbund) and Kao (Nat Kitcharit) met as outsiders in high school, she excelling in English but not much else aside from her love of plants, and Kao obsessed with the art of sport stacking and dreaming of becoming a champion. 10 years later the pair are still a couple, kind of, living in a well-appointed home which they technically co-own though its clear Jay is shouldering the mortgage along with all the other domestic responsibilities. Kao is technically arrested in childhood, spending all of his time shut up in his room practicing sport stacking oblivious that others in his life have sacrificed themselves on his behalf. Jay used to think that it was all worth it as long as Kao achieved his sport stacking dreams but now she’s reached a crisis point realising that for everything she’s done for Kao she’s got very little back and if she waits much longer her own small dream of becoming a mother and having a conventional family life may pass her by.

There is something of an irony in the fact that all of Kao’s major challengers are young children though as he points out sport stacking is an egalitarian sport in which things like age, gender, and nationality are irrelevant. Having successfully broken a record, Kao begins receiving creepy phone calls from a new rival, Edward, a little boy in Colombia who complains to his mother asking why people can’t go on stacking forever only for her to point out that adults have other things in their lives they have to attend to though Edward simply doesn’t understand. To begin with, Kao doesn’t either because he’s been lucky enough to be surrounded by people who supported his dream and went out of their way to make it easy for him by relieving him of basic tasks so that he could devote himself entirely to sport stacking. Because it had always been this way, it never really occurred to Kao that he needed to grow up and begin taking some responsibility for himself or at least acknowledge the sacrifices others were making on his behalf.

When Jay eventually leaves him fearful that she’s wasted too much time and he’s never going to change, Kao is suddenly confronted by the frightening world of adulthood in which he must finally learn to look after himself while simultaneously accepting that it’s alright to ask for and receive help while helping others in return. What appealed to him about sport stacking was that it could be done alone, yet he failed to use the sport to block out everything else but was perpetually bothered by the intrusions of ordinary life his concentration ruined by the slightest noise. What he learns is that he cannot, and does not want to, win alone but only thanks to the support he receives from those around him while accepting that perhaps it’s time to move on from competitive sport stacking.

Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit throws in plenty of meta references as Kao breaks the fourth wall or laments that he thought this was supposed to be an action movie but he’s hardly done any stacking at all and people might be disappointed. An extended running gag directly references Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, while one of the kids Kao teaches at the sport stacking club talks like a gangster because she’s apparently watched too much John Wick. Even so, the relationship between Jay and Kao is drawn with a poignant naturalism rather than rom-com superficiality that allows Kao to accept that it’s time for them both to do what makes them happy even if that means they may not be able to stay together while little Edward seems to come to the same conclusion, ahead of the game in realising that a prize you don’t really want may not be worth winning.

Fast & Feel Love screened as part of this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Images: ©2022 GDH 559 Co., Ltd.