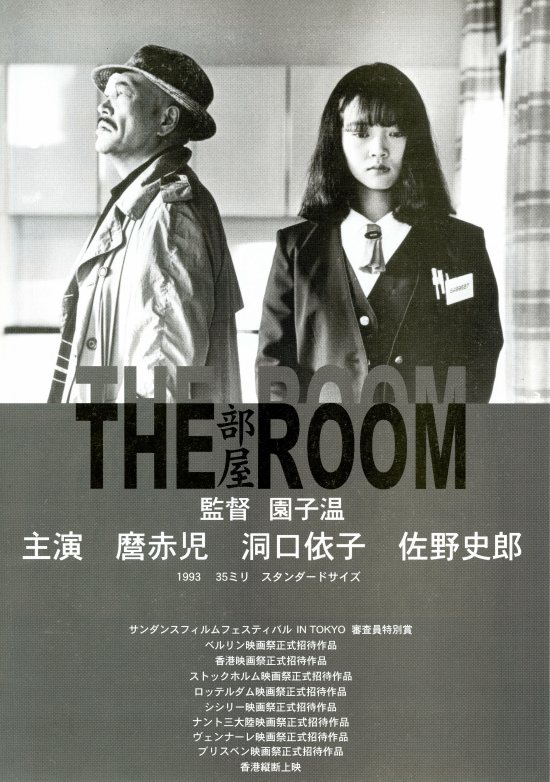

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent.

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent.

Sono begins the film with an uncomfortably long static camera shot of a warehouse area where nothing moves until a man suddenly turns a corner and sits down on a bench. We then cut to a rear shot of the same man who’s now sitting facing a harbour filled with boats coming and going as the sun bounces of the rippling sea. We don’t know very much about him but he’s dressed in the crumpled mac and fedora familiar to every fan of hardboiled fiction and walks with the steady invisibility of the typical genre anti-hero.

Before we head into the main “narrative” such as it is, Sono presents us with another uncomfortably long shot of the title card which takes the form of a street sign simply reading The Room, over which someone is whistling a traditional Japanese tune. Eventually we catch up with the hitman as he meets a young female estate agent identified only by the extremely long number she wears on the jacket of her official looking business suit. The hitman gruffly lists his poetical demands for his new home – must be quiet, have the gentle smell of spring flowers wafting through it, and above all it must have an open, unoverlooked view from a well lit window. The estate agent reacts with dispassionate efficiency, her gaze vacantly directed at the floor or around the rundown apartments which she recommends to her client. Together, the pair travel the city looking for the elusive “Room” though perhaps that isn’t quite what they’re seeking after all.

Sono shoots the entire film in grainy black and white and in academy ratio. He largely avoids dialogue in favour of visual storytelling though what dialogue there is is direct, if poetic, almost symbolic in terms of tone and delivery. The occasional intrusion of the jazzy score coupled with the deserted streets and stark black and white photography underlines the noir atmosphere though like the best hardboiled tales this is one filled emptiness led by a man seeking the end of the world, even if he doesn’t quite know it.

In fact, the relationship between our hitman and the passive figure of the estate agent can’t help but recall Lemmy Caution and the unemotional Natasha from Godard’s Alphaville – also set in an eerily cold city. If Sono is channelling Godard for much of the film, he also brings in a little of Tarkovsky as the hitman and estate agent make an oddly arduous train journey around the city looking for this magical space much like the explorers of the Zone in Stalker. Yet for all that there’s a touch of early Fassbinder too in Sono’s deliberately theatrical staging which attempts both to alienate and to engage at the same time.

The Room’s central conceit is its use of extremely long shots filled with minimal action or movement. In a 90 minute film, Sono has given us only 44 takes, lingering on empty streets and abandoned buildings long enough to test the patience of even the most forgiving viewer. Deliberately tedious, The Room won’t counter arguments of indulgence but its increasing minimalism eventually takes on a hypnotic quality, lending to its dreamlike, etherial atmosphere.

Here the city seems strange, a half formed place made up of half remembered images and crumbling buildings. Empty trains, scattered papers, and lonely bars are its mainstays yet it’s still somehow recognisable. Leaning more towards Sono’s poetic ambitions than the anarchism of his more aggressive work, The Room is a beautifully oblique exploration of the landscape of a tired mind as it prepares to meet the end of its journey.

Original trailer (no subtitles):

Yoji Yamada’s films have an almost Pavlovian effect in that they send even the most hard hearted of viewers out for tissues even before the title screen has landed. Kabei (母べえ), based on the real life memoirs of script supervisor and frequent Kurosawa collaborator Teruyo Nogami, is a scathing indictment of war, militarism and the madness of nationalist fervour masquerading as a “hahamono”. As such it is engineered to break the hearts of the world, both in its tale of a self sacrificing mother slowly losing everything through no fault of her own but still doing her best for her daughters, and in the crushing inevitably of its ever increasing tragedy.

Yoji Yamada’s films have an almost Pavlovian effect in that they send even the most hard hearted of viewers out for tissues even before the title screen has landed. Kabei (母べえ), based on the real life memoirs of script supervisor and frequent Kurosawa collaborator Teruyo Nogami, is a scathing indictment of war, militarism and the madness of nationalist fervour masquerading as a “hahamono”. As such it is engineered to break the hearts of the world, both in its tale of a self sacrificing mother slowly losing everything through no fault of her own but still doing her best for her daughters, and in the crushing inevitably of its ever increasing tragedy.

Kinuyo Tanaka was one of the most successful actresses of the pre-war years well known for her work with celebrated director Kenji Mizoguchi including several of his most critically acclaimed works such as Sansho the Bailiff, Ugetsu, and The Life of Oharu. However, post-war Japan was a very different place and Tanaka had a different kind of ambition. With 1953’s Love Letter (恋文, Koibumi) she became Japan’s second ever female feature film director, though her working and personal relationship with Mizoguchi ended when he attempted to block her access to the Director’s Guild of Japan. No one quite knows why he did this and he tried to go back on it later but the damage was done, Tanaka never forgave him for this very public betrayal. Whatever Mizoguchi may have been thinking, he was very wrong indeed – Tanaka’s first venture behind the camera is an extraordinarily interesting one which is not only a technically solid production but actively seeks a new kind of Japanese cinema.

Kinuyo Tanaka was one of the most successful actresses of the pre-war years well known for her work with celebrated director Kenji Mizoguchi including several of his most critically acclaimed works such as Sansho the Bailiff, Ugetsu, and The Life of Oharu. However, post-war Japan was a very different place and Tanaka had a different kind of ambition. With 1953’s Love Letter (恋文, Koibumi) she became Japan’s second ever female feature film director, though her working and personal relationship with Mizoguchi ended when he attempted to block her access to the Director’s Guild of Japan. No one quite knows why he did this and he tried to go back on it later but the damage was done, Tanaka never forgave him for this very public betrayal. Whatever Mizoguchi may have been thinking, he was very wrong indeed – Tanaka’s first venture behind the camera is an extraordinarily interesting one which is not only a technically solid production but actively seeks a new kind of Japanese cinema.

The Snow Woman is one of the most popular figures of Japanese folklore. Though the legend begins as a terrifying tale of an evil spirit casting dominion over the snow lands and freezing to death any men she happens to find intruding on her territory, the tale suddenly changes track and far from celebrating human victory over supernatural malevolence, ultimately forces us to reconsider everything we know and see the Snow Woman as the final victim in her own story. Previously brought the screen by Masaki Kobayashi as part of his

The Snow Woman is one of the most popular figures of Japanese folklore. Though the legend begins as a terrifying tale of an evil spirit casting dominion over the snow lands and freezing to death any men she happens to find intruding on her territory, the tale suddenly changes track and far from celebrating human victory over supernatural malevolence, ultimately forces us to reconsider everything we know and see the Snow Woman as the final victim in her own story. Previously brought the screen by Masaki Kobayashi as part of his  Every once in a while an artist emerges whose work is so far ahead of its time that the audience of the day is unwilling to accept but generations to come will finally recognise for the achievement it represents. So it is for Sharaku – a young man whose abilities and ambitions are ruthlessly manipulated by those around him for their own gain. Brought to the screen by veteran new wave director Masahiro Shinoda, Sharaku (写楽) is an attempt to throw some light on the life of this mysterious historical figure who comes to symbolise, in many ways, the turbulence of his era.

Every once in a while an artist emerges whose work is so far ahead of its time that the audience of the day is unwilling to accept but generations to come will finally recognise for the achievement it represents. So it is for Sharaku – a young man whose abilities and ambitions are ruthlessly manipulated by those around him for their own gain. Brought to the screen by veteran new wave director Masahiro Shinoda, Sharaku (写楽) is an attempt to throw some light on the life of this mysterious historical figure who comes to symbolise, in many ways, the turbulence of his era. If you wake up one morning and decide you don’t like the world you’re living in, can you simply remake it by imagining it differently? The world of Hanging Garden (空中庭園, Kuchu Teien), based on the novel by Mitsuyo Kakuta, is a carefully constructed simulacrum – a place that is founded on total honesty yet is sustained by the willingness of its citizens to support and propagate the lies at its foundation. This is

If you wake up one morning and decide you don’t like the world you’re living in, can you simply remake it by imagining it differently? The world of Hanging Garden (空中庭園, Kuchu Teien), based on the novel by Mitsuyo Kakuta, is a carefully constructed simulacrum – a place that is founded on total honesty yet is sustained by the willingness of its citizens to support and propagate the lies at its foundation. This is

The second of the only three extant films directed by Sadao Yamanaka in his intense yet brief career, Kochiyama Soshun (河内山宗俊, oddly retitled “Preist of Darkness” in its English language release) is not as obviously comic or as desperately bleak as the other two but falls somewhere in between with its meandering tale of a stolen (ceremonial) knife which precedes to carve a deep wound into the lives of everyone connected with it. Once again taking place within the realm of the jidaigeki, Kochiyama Soshun focuses more tightly on the lives of the dispossessed, downtrodden, and criminal who invoke their own downfall by attempting to repurpose and misuse the samurai’s symbol of his power, only to find it hollow and void of protection.

The second of the only three extant films directed by Sadao Yamanaka in his intense yet brief career, Kochiyama Soshun (河内山宗俊, oddly retitled “Preist of Darkness” in its English language release) is not as obviously comic or as desperately bleak as the other two but falls somewhere in between with its meandering tale of a stolen (ceremonial) knife which precedes to carve a deep wound into the lives of everyone connected with it. Once again taking place within the realm of the jidaigeki, Kochiyama Soshun focuses more tightly on the lives of the dispossessed, downtrodden, and criminal who invoke their own downfall by attempting to repurpose and misuse the samurai’s symbol of his power, only to find it hollow and void of protection. Sadao Yamanaka had a meteoric rise in the film industry completing 26 films between 1932 and 1938 after joining the Makino company at only 20 years old. Alongside such masters to be as Ozu, Naruse, and Mizoguchi, Yamanaka became one of the shining lights of the early Japanese cinematic world. Unfortunately, this light went out when Yamanaka was drafted into the army and sent on the Manchurian campaign where he unfortunately died in a field hospital at only 28 years old. Despite the vast respect of his peers, only three of Yamanaka’s 26 films have survived. Tange Sazen: The Million Ryo Pot (丹下左膳余話 百萬両の壺, Tange Sazen Yowa: Hyakuman Ryo no Tsubo) is the earliest of these and though a light hearted effort displays his trademark down to earth humanity.

Sadao Yamanaka had a meteoric rise in the film industry completing 26 films between 1932 and 1938 after joining the Makino company at only 20 years old. Alongside such masters to be as Ozu, Naruse, and Mizoguchi, Yamanaka became one of the shining lights of the early Japanese cinematic world. Unfortunately, this light went out when Yamanaka was drafted into the army and sent on the Manchurian campaign where he unfortunately died in a field hospital at only 28 years old. Despite the vast respect of his peers, only three of Yamanaka’s 26 films have survived. Tange Sazen: The Million Ryo Pot (丹下左膳余話 百萬両の壺, Tange Sazen Yowa: Hyakuman Ryo no Tsubo) is the earliest of these and though a light hearted effort displays his trademark down to earth humanity.