The Japan Academy Film Prize, Japan’s equivalent of the Oscars awarded by the Nippon Academy-Sho Association of industry professionals, has announced the winners for its 46th edition which honours films released Jan. 1 – Dec. 31, 2022 that played in a Tokyo cinema at least three times a day for more than two weeks. Favourite A Man swept the board winning eight of the 13 Awards it was nominated for including big ticket items Picture, Director, Screenplay, Actor, Supporting Actor, and Supporting Actress. Meanwhile, big budget tokusatsu Shin Ultraman has a good showing in technical categories.

Picture of the Year

- A Man

- Shin Ultraman

- Phases of the Moon

- Anime Supremacy!

- Wandering

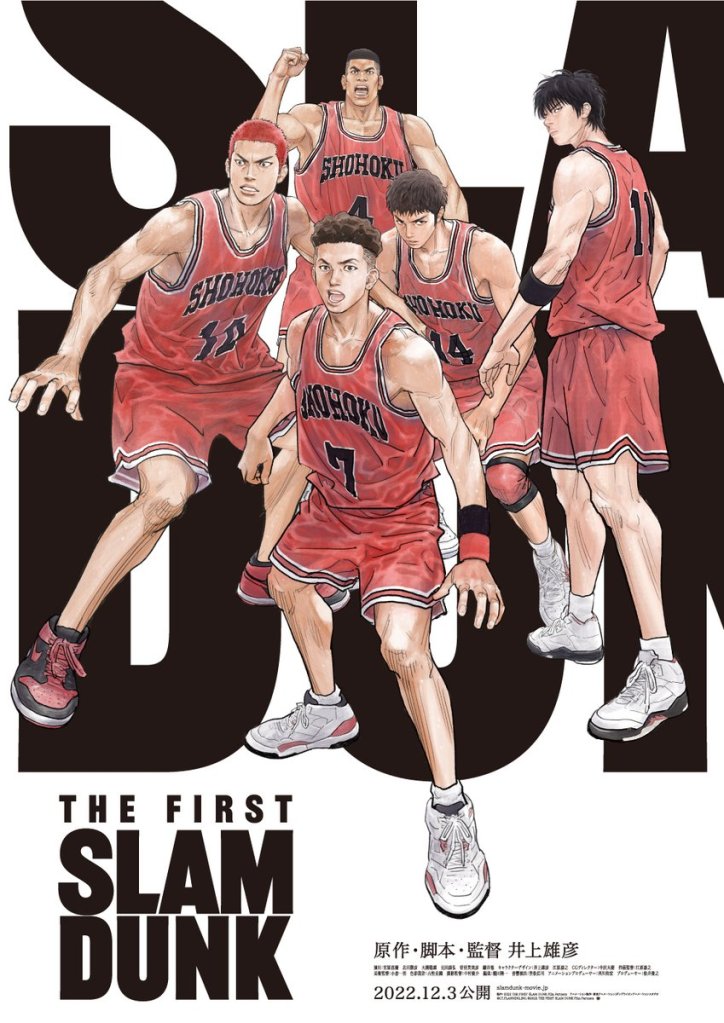

Animation of the Year

- Inu-Oh

- Lonely Castle in the Mirror

- Suzume

- One Piece Film Red

- The First Slam Dunk

Director of the Year

- Kei Ishikawa (A Man)

- Takashi Koizumi (The Pass: Last Days of the Samurai)

- Shinji Higuchi (Shin Ultraman)

- Ryuichi Hiroki (Phases of the Moon)

- Kohei Yoshino (Anime Supremacy!)

Screenplay of the Year

- Takashi Koizumi (The Pass: Last Days of the Samurai)

- Hashimoto Hiroshi (Phases of the Moon)

- Chie Hayakawa (Plan 75)

- Yosuke Masaike (Anime Supremacy!)

- Kosuke Mukai (A Man)

Outstanding Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role

- Sadao Abe (Lesson in Murder)

- Yo Oizumi (Phases of the Moon)

- Satoshi Tsumabuki (A Man)

- Kazunari Ninomiya (Fragments of the Last Will)

- Tori Matsuzaka (Wandering)

Outstanding Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role

- Yukino Kishii (Small, Slow But Steady)

- Non (The Fish Tale)

- Chieko Baisho (Plan 75)

- Suzu Hirose (Wandering)

- Riho Yoshioka (Anime Supremacy!)

Outstanding Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role

- Tasuku Emoto (Anime Supremacy!)

- Masataka Kubota (A Man)

- Kentaro Sakaguchi (Hell Dogs)

- Ren Meguro (Phases of the Moon)

- Ryusei Yokohama (Wandering)

Outstanding Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role

- Kasumi Arimura (Phases of the Moon)

- Sakura Ando (A Man)

- Machiko Ono (Anime Supremacy!)

- Nana Seino (A Man, Kingdom 2: To Distant Lands)

- Mei Nagano (Motherhood)

- Honoka Matsumoto (It’s in the Woods)

Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography

- Osamu Ichikawa / Keizo Suzuki (Shin Ultraman)

- Shoji Ueda / Hiroyuki Kitazawa (The Pass: Last Days of the Samurai)

- Ryuto Kondo (A Man)

- Akira Sato (Kingdom 2: To Distant Lands)

- Hong Kyung-pyo (Wandering)

Outstanding Achievement in Lighting Direction

- Sosuke Yoshikado (Shin Ultraman)

- Hideaki Yamakawa (The Pass: Last Days of the Samurai)

- Kenjiro So (A Man)

- Hiroyuki Kase (Kingdom 2: To Distant Lands)

- Yuki Nakamura (Wandering)

Outstanding Achievement in Music

- Yoshihiro Ike (Anime Supremacy!)

- Yu Takami (Whisper of the Heart)

- Cicada (A Man)

- Mari Fukushige (Phases of the Moon)

- Radwimps / Kazuma Jinnouchi (Suzume)

Outstanding Achievement in Art Direction

- Toshihiro Isomi / Emiko Tsuyuki (Fragments of the Last Will)

- Hidetaka Ozawa (Kingdom 2: To Distant Lands)

- Satoshi Kanda (Anime Supremacy!)

- Yuji Hayashida / Eri Sakushima (Shin Ultraman)

- Hiroyuki Wagatsuma (A Man)

Outstanding Achievement in Sound Recording

- Takeshi Ogawa (A Man)

- Hironobu Tanaka (recording) / Haru Yamada (sound design) (Shin Ultraman)

- Akira Fukada (Phases of the Moon)

- Masahito Yano (The Pass: Last Days of the Samurai)

- Kazushiko Yokono (Kingdom 2: To Distant Lands)

Outstanding Achievement in Film Editing

- Hideto Aga (The Pass: Last Days of the Samurai)

- Kei Ishikawa (A Man)

- Soichi Ueno (Anime Supremacy!)

- Yohei Kurihara / Hideaki Anno (Shin Ultraman)

- Minoru Nomoto (Phases of the Moon)

Outstanding Foreign Language Film

- Avatar: The Way of Water

- Coda

- Spider-Man: No Way Home

- Top Gun: Maverick

- RRR

Newcomer of the Year

(Presented to all nominees equally)

- Karin Ono (Anime Supremacy!)

- Hinako Kikuchi (Phases of the Moon)

- Riko Fukumoto (Even if This Love Disappears from the World Tonight)

- Meru Nukumi (My Boyfriend in Orange)

- Daiki Arioka (Shin Ultraman)

- Ichiro Banka (Sabakan)

- Hokuto Matsumura (xxxHOLiC)

- Ren Meguro (Phases of the Moon)

Special Award from the Association

(Lifetime achievement awards)

- Masanobu Amemiya (car stunts)

- Shohei Kawamoto (animation background art)

- Naomi Koike (production design)

- Yasuhiro Fukuoka (casting producer)

Award for Distinguished Service from the Chairman

(Lifetime achievement awards for contribution to the film industry)

- Shunya Ito (film director)

- Yuzo Kayama (actor)

- Hideki Mochizuki (lighting)

Special Award from the Chairman

(Lifetime achievement award presented to members of the film industry who passed away during 2022)

- Hideo Onchi (film director)

- Hiro Matsuda (screenwriter)

- Mitsunobu Kawamura (producer)

- Iwao Ishii (editor)

- Kazuki Omori (director & screenwriter)

- Yoichi Sai (director & screenwriter)

Special Award

- One Piece Film Red music crew

Popularity Awards

(Decided via public vote)

Movie: One Piece Film Red

Actor: Hokuto Matsumura (Suzume / xxxHOLiC)

Source: Japan Academy Film Prize official website, Eiga Natalie