Turns out, if you want to get away with murder in South Korea all you need to do is remain polite, put on a regular business suit, and carry a fancy briefcase. Three women find themselves pursued by the walking embodiment of destructive patriarchy in Kwon Oh-seung’s extraordinarily tense serial killer thriller Midnight (미드나이트) in which a creepy night stalker exploits male privilege and societal prejudice while relentlessly pursuing his prey through the darkened streets of Seoul.

Our heroine, Kyung-mi (Jin Ki-joo), is a deaf woman working as a customer service representative for the “Care for You” call centre catering to callers who require sign language assistance. The company, however, is not especially caring and makes little effort to include Kyung-mi in office life, leaving her feeling left out and excluded. She attempts to bring this up with her boss when some of the other women complain about being forced to attend an after hours drinking party to entertain clients, but is greeted only with grudging acceptance. At the dinner, meanwhile, the boorish male guests make lewd comments about her appearance assuming she can’t hear them, though she can of course lipread and returns in kind by insulting them in sign language. To get over her sense of discomfort she dreams of travelling to Jeju island for a relaxing beach holiday with her mother (Gil Hae-yeon) who is also deaf.

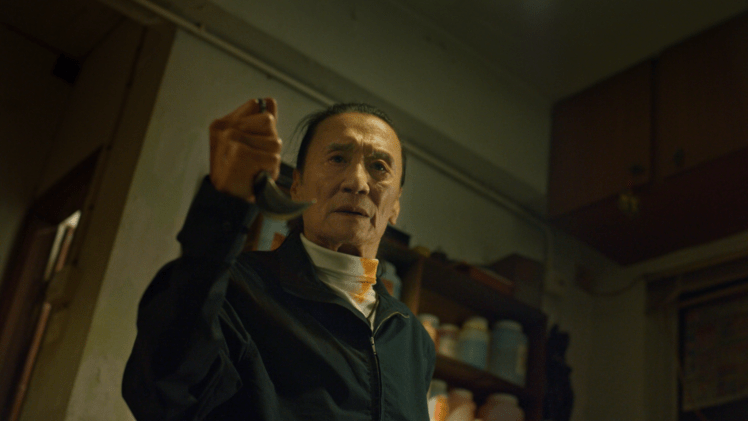

Across town, meanwhile, 20-something So-jung (Kim Hye-yoon) is arguing with her security guard brother Jung-tak (Park Hoon) about her outfit for an upcoming blind date. Jung-talk sets a 9pm curfew he later increases to 10 which seems at best over protective, though as it turns out he’s right to worry as not long after 10pm when So-jung is almost home she’s nabbed by vicious serial killer Do-sik (Wi Ha-joon), stabbed, and left in an alley where she manages to attract the attention of a passing Kyung-mi by throwing her white stilettos into the road. In her effort to help, Kyung-mi unwittingly becomes a target for the crazed axe murderer who continues to pursue her despite having ascertained that she cannot identify him.

Do-sik manages to get away with his crimes by adopting the non-threatening persona of a mild-mannered office worker, swapping his medical mask, baseball cap and hoodie for a regulation issue grey suit and carrying a leather briefcase which turns out to be full of knives and other murdery equipment though of course no one is going to look inside. Ironically he tells Kyung-mi that he’s looking for his sister, trying to earn her trust by convincing her to show him where she last saw So-jung, a ruse which both echoes Jung-tak’s parallel search and his later claim that Kyung-mi is his younger sister apparently in a state of mental distress. He even goes with Kyung-mi and her mother to the police station where gets into a fight with Jung-tak who’s figured out he has his sister only for the police to mistakenly taser the angry man in a shell suit, sending the nice man in a suit on his way with a series of friendly bows and apologies.

Kyung-mi and her mother meanwhile are rendered doubly vulnerable because of their deafness, unable to hear danger approaching while equally unable to communicate with impatient police officers and passersby even if they are able to silently communicate with each other in ways others can’t understand. Kyung-mi repeatedly hits a panic button on a lamppost that activates the streetlight and contacts local police, but there are no cameras, she can’t hear them and they have no idea why she isn’t speaking. Making a break for it, she ends up in downtown Seoul but to the bystanders who surround her she’s a crazy lady with a knife rather than a young woman pursued by a predatory man. Unable to explain the situation, she is even handed back to Dong-sik who claimed to be her brother by a trio of smug soldiers who find her hiding behind some bins and assume they’re helping by returning a mentally disturbed woman to her responsible adult.

Yet big brothers make poor protectors. Jung-tak had been so concerned about his sister’s outfit, worryingly overprotective in obsessing over unreturned messages, but in the end it didn’t matter Dong-sik picked her for convenience’s sake. Even the first woman we see Dong-sik snatch was left to walk home in the dark by unchivalrous male colleagues who stole her taxi, chatting to her boyfriend about fried chicken but ultimately paying the price for (wisely) refusing to get into Dong-sik’s van. Dong-sik is only able to get away with his crimes by assuming his male privilege, playing the part of the respectable executive and caring big brother while the police, the ultimate authority figures, defer to him refusing to take Kyung-mi’s claims seriously in an echo of the baseline misogyny displayed by her clients at work.

The only way to make them listen, she discovers, is in a public act of self harm that ironically exposes Dong-sik for what he really is. Taking place in near real time, Kwon’s extraordinarily tense cat and mouse game finds Kyung-mi desperately trying to escape the midnight city pursued by patriarchal violence and finding little support in an ableist society as she desperately tries not only to save herself but the other women similarly trapped in a labyrinth of seemingly inescapable threat.

Midnight streamed as part of this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)