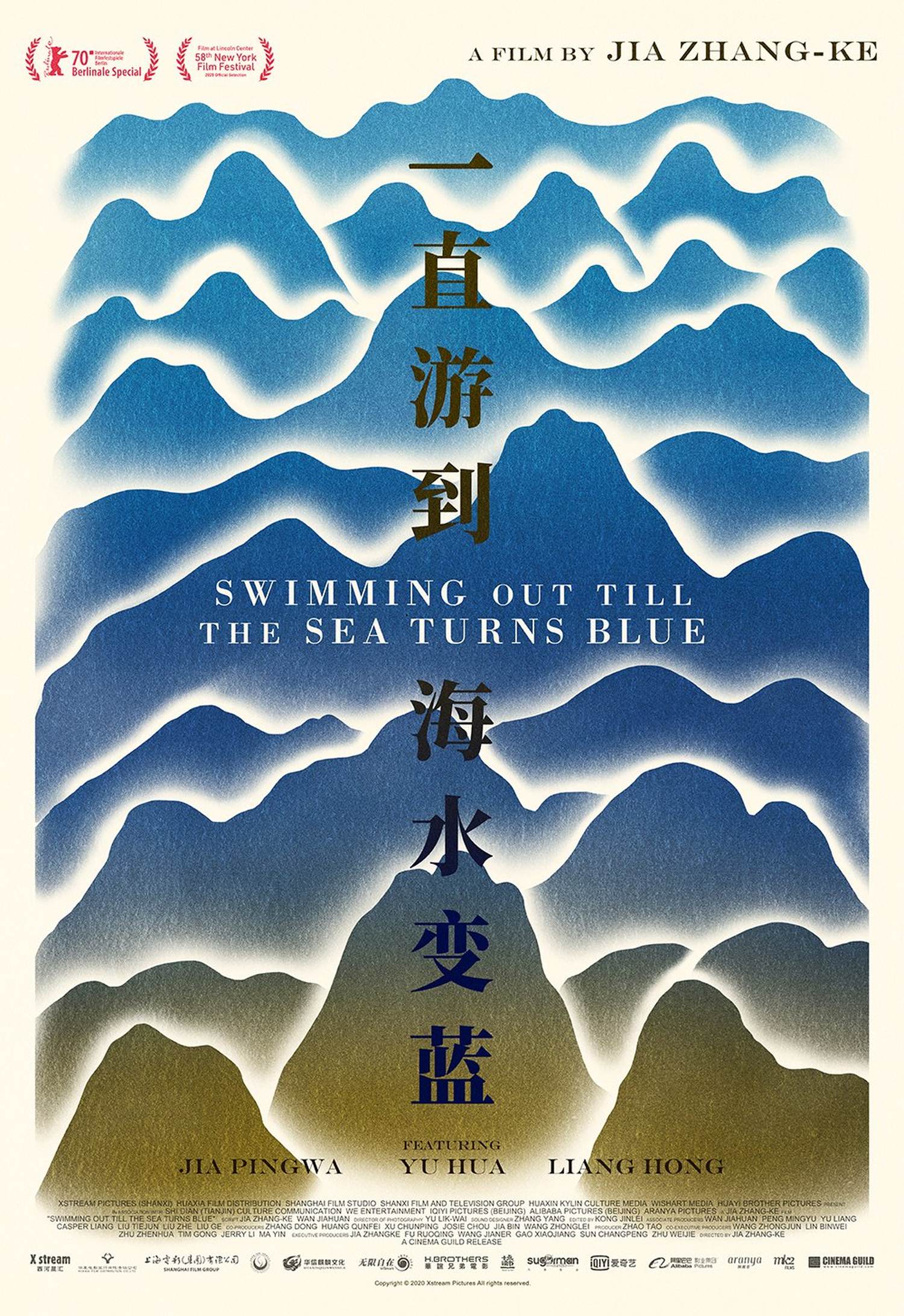

Returning to his rural hometown, Jia Zhangke embarks on an alternate history of China in the 20th century through the prism of literature in the poetically titled documentary Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue (一直游到海水变蓝, Yīzhí Yóu Dào Hǎishuǐ Biàn Lán). Taking its title from an off the cuff though strangely profound comment from the witty and loquacious Yu Hua, Swimming is the third in a loose series of documentaries focussing on artists following Dong and Useless each of which were completed over a decade ago.

Signalling his intentions early on, Jia opens with a lengthy sequence of elderly people in a canteen. The first of his 18 chapters is titled simply “eating”, and as we quickly infer hunger will be a constant background presence for each of our writers who recount their sometimes difficult rural childhoods and the paths which eventually led to them becoming chroniclers of provincial life. The earliest stretches are dedicated to legendary author Ma Feng who passed away in 2004 but it’s some time before we even get to his literary work, struck as we are by his role as an agrarian moderniser who ingeniously saved his village through collective action, bringing the villagers together in a plan to purify the water before irrigation to reduce the alkaline quality of the soil which had made it impossible to farm. Eventually we’re introduced to Ma’s daughter who begins to fill in his biography from a personal perspective while explaining how it was that he came to be known for his naturalistic depictions of the lives of ordinary rural folk in the early days of Communism.

That idealism soon takes on a darker hue, however, in the story of Jia Pingwa who recounts his childhood during the Cultural Revolution in which his father was sent sent away for “re-education” after being falsely accused of receiving training as a KMT spy in the ‘40s. In Jia Pingwa’s early childhood eating was indeed a concern, something which he later says caused tension in the family that was only eased by the presence of his grandmother but even she couldn’t keep them all together after the institution of the communal kitchen. Perhaps more austere than you’d expect, Jia Pingwa admonishes his daughter, also a published poet, that she should fulfil her role as a wife and mother before that as artist, and that being a poet doesn’t always mean one lives poetically. Nevertheless he recounts the widening of horizons which occurred as China began to open up in 1980s, an influx of foreign art that introduced him to “the West” but also left him in an artistic quandary in the search for new yet authentic directions.

A little younger than Jia Pinghua, the 1980s is when the extremely animated Yu Hua came of age, revealing an unexpected effect of the Cultural Revolution that led to his artistic destiny as he found himself re-imagining the endings of books which had long since fallen apart and existed for him only in fragments. Training first as a dentist but finding it not to his liking, Yu Hua longed to broaden his horizons and began writing seriously with the hope of getting a better job, eventually enrolling in university in Beijing in 1989 which he recounts somewhat incongruously as cheerfully uneventful.

There is indeed a kind of micro framing in Jia’s concentration on rural China as a place to one side of wider society or politics. Just as Yu Hua casually ignores the reasons why others might find it interesting to have been a student in Beijing in 1989, Liang Hong opens by recounting that the year was 1997 which was the year Hong Kong returned to China but she was so busy that as an event it hardly registered for her. Like Yu and Jia Pingwa she recounts a difficult rural childhood in which her mother was rendered ill and later died due to the demands of country living while her kindhearted though feckless father struggled to manage his small family. While the men concentrate on their own paths, Liang mostly talks of her family, the sister who sacrificed her future for her siblings, and later her own son who talks of learning about his history through mother’s books though he no longer remembers the rural dialect and his associations with the area are mainly to do with playing with his cousins on visits to his mother’s family home.

Liang’s son is the last and least deliberately staged of Jia’s frequent cutaways to local people reciting brief snippets of literature by the four authors and others often in praise of the land. Between lengthy talking head sequences, he switches from present day to historical stock footage showcasing the lives of ordinary people as they play cards, eat, or hurry on their way from one place to another. Spiralling out and away from Fenyang and back around again what Jia presents is less a literary survey than a rural history which is in its own way also mythologised as the wounded soul of the modern China.

Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue screens at the BFI Southbank on 24th July as part of this year’s Chinese Visual Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)