“Hello World” is a phrase familiar to many as the first line of text given to a new program. It signals firstly that the code is functioning correctly, but also expresses a sense of excitement and positivity as if a new entity were standing on the shores of an unfamiliar land eager for adventure. Tomohiko Ito’s sci-fi-inflected anime carefully places the phrase not at its beginning but at its conclusion, affirming that the hero has managed to step into himself, discover his place, and come to an understanding that grants him a sense of agency and possibility in a brand new world that is in a sense of his own creation and choosing.

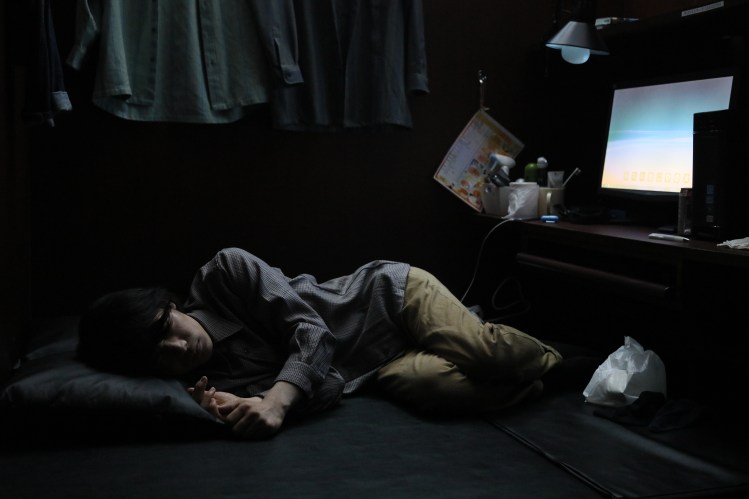

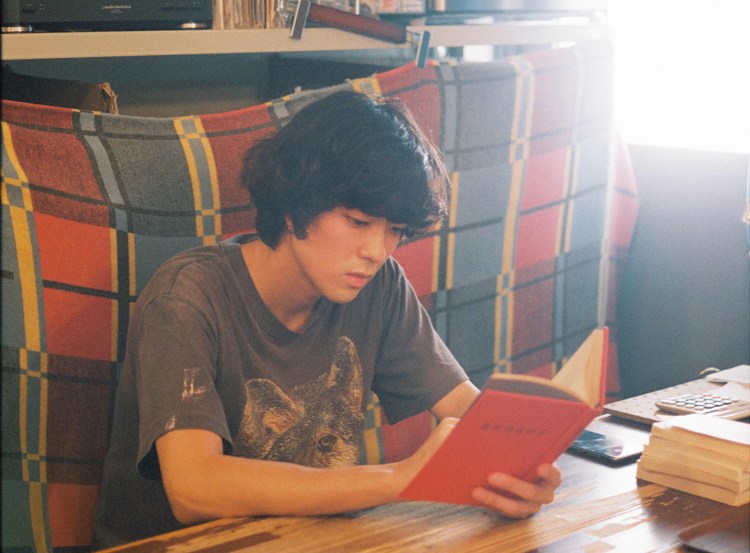

Before all that, however, Naomi Katagaki (Takumi Kitamura) is a textbook “regular high school boy” who fears he is just an extra in his own life quietly reading away at the back of the classroom and last in line in the dinner queue. Reading a self-help book on becoming more assertive helps less than he might have hoped, but two changes are slowly introduced into his life albeit passively the first being he is press-ganged onto the library committee and the second that he is approached by a strange man who claims to be himself a decade older. Future Naomi (Tori Matsuzaka) claims not to have come from another time but from “reality”, explaining that the world Naomi currently inhabits is a simulacrum designed to perfectly preserve the city of Kyoto as a digital archive housed inside supercomputer Alltale which has infinite memory. His older self tells him that he is fated to fall in love with classmate Ruri (Minami Hamabe) but she will then be killed by a lightning strike at a festival in three months’ time. Though their actions will have no effect on the “real” world, Future Naomi claims it’s enough for him to “save” Ruri even if it’s only virtually seemingly caring little that he will in fact be completely ruining the Chronicle Kyoto project by introducing a note of the inauthentic perfectly primed for the butterfly effect.

In any case, what Naomi eventually discovers is that you can’t always trust “yourself” especially if you’re apparently merely data and therefore perhaps infinitely expendable. Young Naomi doesn’t seem particularly fazed by the revelation that his world is not “real”, and is perhaps overly trusting of his new mentor’s guidance following his instructions to the letter in accordance with the “Ultimate Manual” he’s been given to facilitate his romance with Ruri whom he originally claims not to fancy because like many immature teenage boys he only likes “cute” girls like transfer student Misuzu (Haruka Fukuhara) who literally sparkles while Ruri is like him a wallflower obsessed with books, shy and with an aloof, slightly intense aura. What Future Naomi offers him is pure male adolescent fantasy wish fulfilment in gifting him both the means for romantic success and literal superpowers in the form of the Hand of God which allows him to conjure objects from the digital world and will apparently help to save Ruri from her cruel fate.

The universe, however, has other plans. Soon enough he’s being chased by the forces of order, Homeostasis System Droids, trained to eliminate and correct inconsistencies in data appearing as oversize policemen in kitsune masks. Nothing in Naomi’s world makes much concrete sense, even as he’s been told he’s the creation of a simulacrum. Why would Future Naomi fetch up three months before the accident to train him rather than simply altering code, why would someone bother to create these universal super powers, and what exactly are the connections between this world and the “real” from which Future Naomi claims to have come? Some of this might well be explained by a final twist which turns everything we thought we knew upside down, implying perhaps that the gaps and contradictions we see are down to the vagaries of analogue rather than digital memory mixed with trauma both physical and emotional. Nevertheless, it turns out that Naomi’s mission is less to save Ruri than to save himself twice over, allowing Future Naomi to find an accommodation with the traumatic past while essentially giving birth to a “new world” of adulthood in which he is the fully actualised protagonist rather than the bit-playing extra he’s always believed himself to be.

Featuring character designs by Kyoto Animation stalwart Yukiko Horiguchi, Hello World’s 3D animation fusion of 2D reality and the digital realm makes for interesting production design as Naomi’s world eventually crumbles around him in multi-coloured pixel while he’s chased by giant neon hands under an angry red sky. Nevertheless, its wilful incoherence often proves frustrating even if its myriad plot holes might be explained in part by the final revelation which itself introduces another note of bafflement in its parting scene. Asking some minor questions about the collection, use, and storage of personal data, archival practice, the limits of digital technology, and the nature of “reality”, Hello World is nevertheless a coming of age romance at heart in which the hero saves himself twice over while learning to rediscover a sense of wonder in future possibility.

Hello World streamed as part of the 2021 Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

International trailer (English subtitles)