A blind swordsman takes revenge against the evils of feudal society in Yang Bingjia’s impressively helmed action drama, Eye For An Eye: The Blind Swordsman (目中无人, mùzhōngwúrén). Set in the “lawless” society of the Tang era following the Tianbao rebellion, the film has a western sensibility with its twanging guitar score and dusty roads not to mention jumped up gangsters trying to get a foothold in the legitimate order simply because they have become too powerful and no one is willing to resist them.

Ni Yan (Gao Weiman), a young tavern woman who lost her brother and husband when her wedding was attacked by the Yuwen clan asks for nothing more than “justice” but that’s something no one can give her. Wandering swordsman Cheng Yi (Mo Tse) who’d taken a liking to her because she offered him some of her wine and even gave some to his horse reports the crime to the local magistrate after claiming the bounty on a fugitive, only he tells her directly that he will do nothing because the Yuwen clan have already moved beyond justice and not even he will touch them.

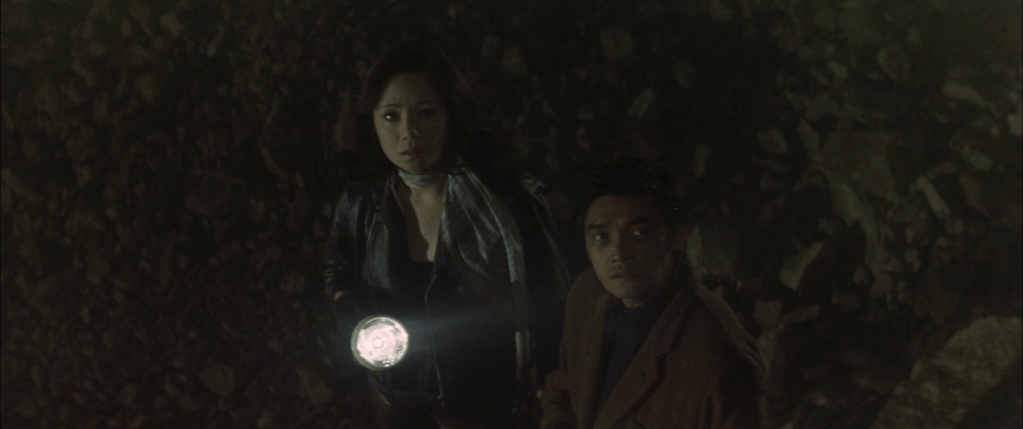

In a way, Cheng is depicted as a failed revolutionary and his blindness a symbol his despair in a world he no longer cares to see. A bounty hunter by trade, his work is facilitated by old comrade Lady Qin (Zhang Qin) who, in contrast to him, seems to live a cheerful life repairing musical instruments while much loved in the town around her. Though they pretend to be saving money for an operation to restore Cheng’s sight, their line of work is perhaps cynical in taking advantage of the times while accidentally outsourcing a justice the authorities can no longer provide in the weakened Tang society. The Yuwen have infiltrated most institutions and cultivated relationships with important people that allow them to ride roughshod over ordinary citizens who are now completely at their mercy.

There might be something quietly subversive in these references to a corrupt and authoritarian institution which tries to brand Ni Yani the criminal in her pleas for justice, insisting that she admit to killing her brother herself in resentment of his criminal past while he is also hunted by the Yuwen because he knows to much about their dodgy dealings including raiding tombs to get precious gems to use as bargaining chips in a dynastic marriage negotiation. Cheng Yi did not originally want to get involved, himself too cynical and having given up hope of “justice” in this “lawless” society, but finds himself sympathetic towards Ni Yan because of the kindness she showed him and the obvious suffering her ordeal has inflicted on her.

In a sense, his eyes are opened to the injustice of the society around him to which he had been wilfully blind if ironically accepting that he will never see again. He alone is willing to stand up to the Yuwen while even within their ranks petty resentments are growing as a princeling grows ambitious to escape his own oppression at the hands of an authoritarian brother who berates him for his weakness.

Despite the budgetary issues which often plague straight to streaming cinema, Yang’s elegantly lensed drama brings a real sense of place to the dusty provincial towns where Cheng plies his trade along with the ornate elegance of the realm of Lady Qin whose flowing robes belie her military past. Drawing inspiration from the western as well as Japanese genre classics such as Yojimbo the film presents a world in decay in which the wandering swordsman becomes a moral authority, delivering justice if for a price. The irony is that it isn’t money which opens his eyes, but the reclaimed ability to see with his heart in deciding to help Ni Yan in her quest to avenge the deaths of those close to her. A series of excellently choreographed and well-shot action scenes along with Yang’s post-modern take on the material lend this tale of wandering swordsmen and feudal abuses a sense of the legendary that hints at further adventures for wandering sword for hire Cheng Yi bringing his own brand of justice to a lawless place.

Eye for an Eye: The Blind Swordsman is out in the US on Digital, blu-ray, and DVD on 28th November courtesy of Well Go USA.

US trailer (English subtitles)