Japan was well on the way to economic recovery by 1961, but the newly prosperous society also gave rise to other anxieties and most particularly in the light of the Cold War and space race with the nation fearful of falling behind in scientific development. Or at least, that’s something that particularly bothers the young heroes of Koji Ota’s kids tokusatsu, Invasion of the Neptune Men (宇宙快速船, Uchu Kaisokusen), in which the nation’s failure to build a space rocket is conflated with its traditional visions of masculinity.

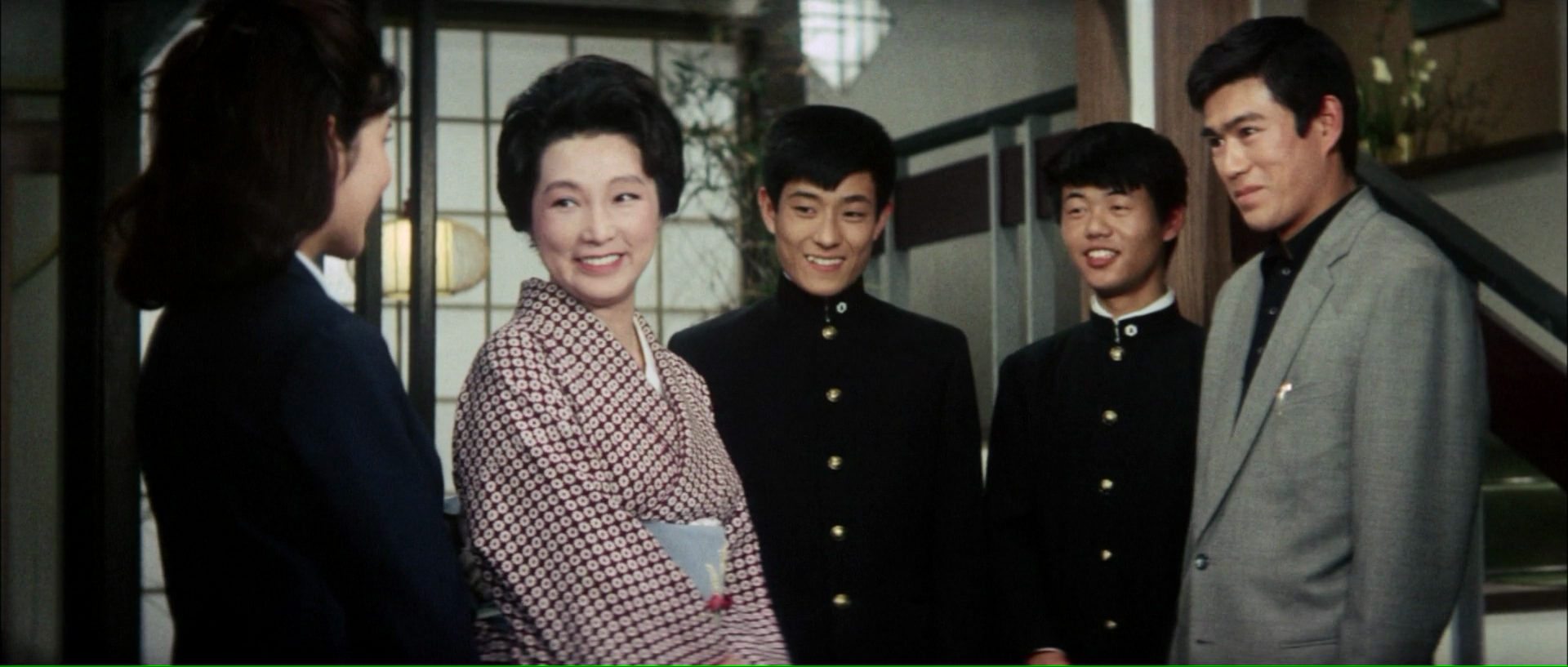

At least, the boys all agree that Tachibana (Shinichi Chiba), a young scientist who runs a kind of club with them at the research facility where he works, is pretty great but also a bit of a wimp who failed to stand up to some bullies who were hassling him at a local cinema. They think it would be better if he were cool, re-imagining him as a kind of tokusatsu hero named “Iron Sharp” for whom they even come up with a theme song. As part of their club activities watching satellites, the kids accidentally stumble across a spaceship belonging to Neptune men who are planning to invade though obviously as they are children no one really believes them until the Neptune men start causing other forms of destruction.

Attacked, the kids are saved by the hero they themselves made up flying in on a car/plane/spaceship though he too doesn’t really have a lot time for them and the kids don’t even really notice he looks a lot like Tachibana who is noticeably absent from the lab whenever he’s around. Even so, this being a kids film the major the problem is that no one else takes the boys very seriously, save Tachibana himself, leaving them to save the day on their own while the grown-ups argue amongst themselves.

Getting people to argue amongst themselves turns out to be part of the aliens’ mission in exploiting Cold War paranoia to start world war three. The first attack results in a mushroom cloud which must have been fairly painful symbolism though the Americans immediately blame Russia who blame the US in return asking if they’re really intent on starting a nuclear war. The kids wonder why grownups are always so suspicious of other countries, hinting at a desire for a less xenophobic society eventually echoed in the calls for worldwide unity to defeat the Neptune men while otherwise repeatedly emphasising that Japan can’t be left behind by the US and Russia in the space race.

Then again, there is something quite troubling in the fact that the invading Neptune men who’ve taken on human form appear as soldiers but wearing prominent feminine makeup, re-echoing the boys’ concerns regarding science and masculinity while introducing a seemingly unintentional dose of homophobia into the threat posed by the aliens who otherwise wield destructive nuclear powers echoing the atomic bomb in using their ray guns to vaporise their targets who then leave shadow imprints of themselves where they disappeared. The main weapon used to combat them is science, Tachibana and his boss, the father of one of the boys, coming up with an ingenious electric shield and then a series of magnetic rockets which allow them to shoot down the Neptunian’s ship.

In this case, science is the “good” force that combats the “bad” use of nuclear weapons this time rendered alien rather than manmade therefore neutering the debate surrounding their use and the responsibilities involved with their discovery. Tachibana, the thinly disguised Iron Sharp, then becomes a hero of science racing round in his custom car and largely defeating the Neptunians through a more primal kind of hand to hand violence while embodying the kind of cool masculinity the boys the otherwise feared he lacked which is to say that unlike his real life guise, Iron Sharp is perfectly capable of standing up to “bullies” like extraterrestrial invaders. Reusing some of the effects footage from The Last War, the film emphasises the need for world unity and the end of the Cold War, but also sells a slightly contradictory, mildly nationalist message insisting that Japan can’t fall far behind technologically or will essentially be at the mercy of Russia and America, Tachibana having travelled to Moscow to assist with the creation of a new spaceship. Spurred on by their adventures, the kids all vow to become great inventors protecting Japan through their innovations, going on to explore Mars and Venus hinting at a new sense of possibility in the post-war society but also mindful of its geopolitical realities.