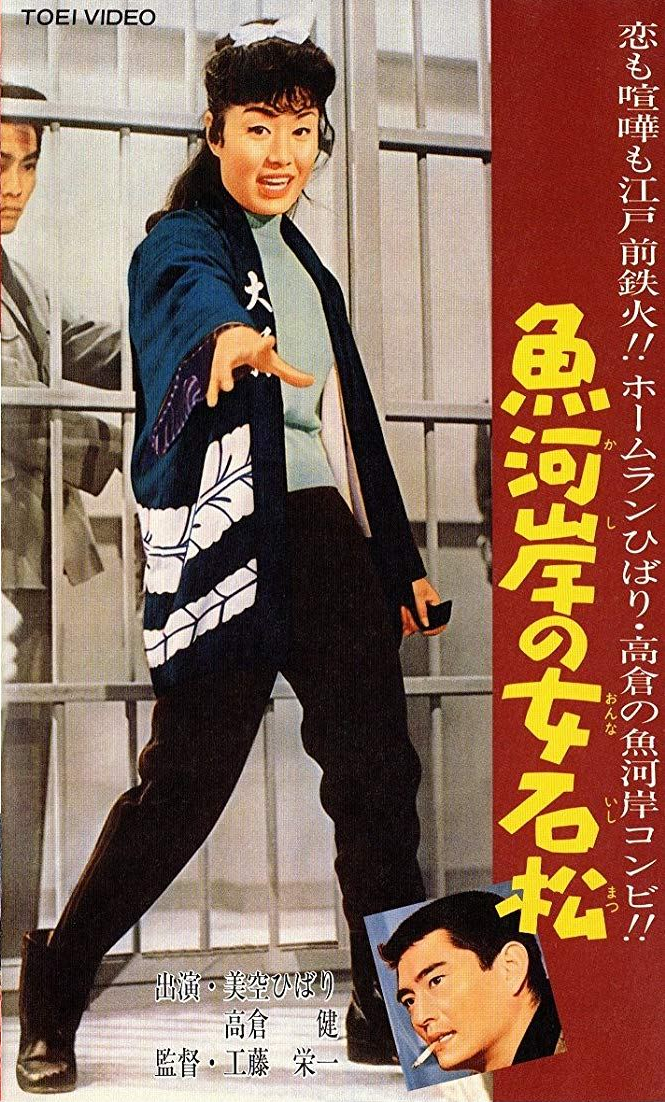

The voice of the post-war era, Hibari Misora also had a long and phenomenally popular run as a tentpole movie star which began at the very beginning of her career and eventually totalled 166 films. Working mostly (though not exclusively) at Toei, she starred in a series of contemporary and period comedies all of which afforded her at least a small opportunity to showcase her musical talents. Directed by Masamitsu Igayama, Feisty Edo Girl Nakanori-san (ひばり民謡の旅シリーズ べらんめえ中乗りさん, Hibari Minyo no Tabi: Beranme Nakanori-san, AKA Travelsongs: Sharp-Tongued Acquaintance) once again stars Hibari Misora as a strong-willed, independent post-war woman who stands up to corruption and looks after the little guy while falling in love with regular co-star Ken Takakura.

The voice of the post-war era, Hibari Misora also had a long and phenomenally popular run as a tentpole movie star which began at the very beginning of her career and eventually totalled 166 films. Working mostly (though not exclusively) at Toei, she starred in a series of contemporary and period comedies all of which afforded her at least a small opportunity to showcase her musical talents. Directed by Masamitsu Igayama, Feisty Edo Girl Nakanori-san (ひばり民謡の旅シリーズ べらんめえ中乗りさん, Hibari Minyo no Tabi: Beranme Nakanori-san, AKA Travelsongs: Sharp-Tongued Acquaintance) once again stars Hibari Misora as a strong-willed, independent post-war woman who stands up to corruption and looks after the little guy while falling in love with regular co-star Ken Takakura.

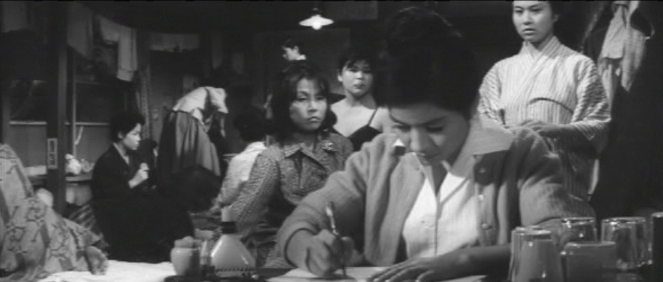

Nobuko (Hibari Misora) is the daughter of a formerly successful lumber merchant whose business is being threatened by an unscrupulous competitor. With her father ill in bed, Nobuko has taken over the family firm but is dismayed to find that a contract she assumed signed has been reneged on by a corrupt underling at a construction company who has been bribed by the thuggish Tajikyo (Takashi Kanda). Unlike Nobuko’s father Sado (Isao Yamagata), Tajikyo is unafraid to embrace the new, completely amoral business landscape of the post-war world and will do whatever it takes to become top dog in the small lumber-centric world of Kibo.

Tajikyo has teamed up with the similarly minded, though nowhere near as unscrupulous, Oka (Yoshi Kato) whose son Kenichi (Ken Takakura) has recently returned from America. Kenichi, having come back to Japan with with clear ideas about the importance of fair practice in business, is not happy with his father’s capitulation to Tajikyo’s bullying. Of course, it also helps that he had a charming meet cute with the spiky Nobuko and became instantly smitten so he is unlikely to be in favour of anything which damages her father’s business even if they are technically competitors.

As in the majority of her films, Misora plays the “feisty” girl of the title, a no nonsense sort of woman thoroughly fed up with the misogynistic micro aggressions she often encounters when trying to participate fully in the running of her family business. Though her father seems happy enough, even if casually reminding her that aspects of the job are more difficult for women – particularly the ones which involve literal heavy lifting and being alone with a large number of men in the middle of a forest, he too remarks on her seeming masculinity in joking that her mother made a mistake in giving birth to her as a girl. Likewise, Tajikyo’s ridiculous plan to have Nobuko marry his idiot son is laughed off not only because Tajikyo is their enemy, but because most people seem to think that Nobuko’s feistiness makes her unsuitable for marriage – something she later puts to Kenichi as their courtship begins to become more serious. Kenichi, of course, is attracted to her precisely because of these qualities even if she eventually stops to wonder if she might need to become more “feminine” in order to become his wife.

To this extent, Feisty Edo Girl is the story of its heroine’s gradual softening as she finally writes home to her father that she is happy to have been born a girl while fantasising about weddings and dreaming of Kenichi’s handsome face. Meanwhile, she also attracts the attentions of an improbable motorcycle champion who just happens to also be the son of a logging family and therefore also able to help in the grand finale even if he never becomes a credible love rival despite Nobuko’s frequent admiration for his fiery, rebellious character which more than matches her own.

Nevertheless, the central concern (aside from the romance) is a preoccupation with corruption in the wartime generation. Where Nobuko’s father Sado is “old fashioned” in that he wants to do business legitimately while keeping local traditions alive, the Tajikyos of the world are content to wield his scruples against him, destroying his business through underhanded methods running from staff poaching to bribery and violence. Kenichi’s father has gone along with Tajikoyo’s plans out of greed and weakness, irritated by his son’s moral purity on one level but also mildly horrified by what he might have gotten himself into by not standing up to Tajikyo in the beginning.

As expected, Nobuko and Kenichi eventually triumph through nothing more than a fierce determination to treat others with respect. Working together cheerfully achieves results, while the corrupt forces of Tajikyo eventually find themselves blocked by those who either cannot be bought or find the strength to refuse to be. Nobuko’s big job is finding prime lumber to be used to build a traditional pagoda in America as part of a cultural celebration. She wants to do her best not only because she takes pride in her work but because she knows this project will represent Japan overseas. Tajikyo, however, would cut corners, believing that the Americans wouldn’t notice even if he sent them rotten logs riddled with woodworm as long as the paperwork tallies. Filled with music and song, Nakanori-san is an action packed outing for Misora in which she once again succeeds in setting the world to rights while falling in love with a likeminded soul as they prepare to sail off into kinder post-war future.

Some of Hibari’s songs from the film (no subtitles):