Summer Holiday Everyday – It’s certainly an upbeat way to describe unemployment but then everything is improbably upbeat and cheerful in the always sunny world of Shusuke Kaneko’s adaptation of Yumiko Oshima’s shoujo manga. Published in the mid-bubble era of 1988, Oshima’s world is one in which anything is possible but by the time of the live action movie release in 1994 perhaps this was not so much the case. Nevertheless, Kaneko’s film retains the happy-go-lucky tone and offers note of celebration for the unconventional as a path to success and individual happiness.

Summer Holiday Everyday – It’s certainly an upbeat way to describe unemployment but then everything is improbably upbeat and cheerful in the always sunny world of Shusuke Kaneko’s adaptation of Yumiko Oshima’s shoujo manga. Published in the mid-bubble era of 1988, Oshima’s world is one in which anything is possible but by the time of the live action movie release in 1994 perhaps this was not so much the case. Nevertheless, Kaneko’s film retains the happy-go-lucky tone and offers note of celebration for the unconventional as a path to success and individual happiness.

Told from the point of view of 14 year old Sugina (Hinako Saeki) who offers us a voiceover guide to her everyday life, Summer Holiday Everyday (毎日が夏休み, Mainichi ga Natsuyasumi) follows the adventures of the slightly unusual Rinkaiji family. Sugina’s mother is divorced from her father and has remarried a successful salary man, himself a divorcee, ten years ago. The family lives in fairly peaceful domesticity and Sugina’s mother, Yoshiko (Jun Fubuki), even remarks how glad she is that her daughter gets on so well with her step-father, Nariyuki (Shiro Sano), though Sugina claims this is largely because she can’t remember actually speaking to him very much over the last ten years.

The pair are about become closer though it risks tearing their perfectly normal family apart. Sugina has been skipping school due to bullying and spends her days in the local park where, unbeknownst to her, her step-father has also been wasting his days after quitting a job he could no longer stand. After getting over the embarrassment of this accidental encounter, Sugina and Nariyuki confess everything to each other and Nariyuki makes a bold decision. Sugina can quit school (seeing as her grades were terrible anyway) and come work with him in his new enterprise – the Rinakaiji Heart Service, helping the community 24/7 with assistance in those difficult to handle odd jobs everyone needs doing.

Quitting a lucrative and secure job for the risk associated with staring a new business is a difficult decision in any society but is more or less unthinkable in Japan. Yoshiko is beyond stunned by her husband’s decision, not to mention the fact that her daughter has been deceiving her by skipping school and faking her report cards to make it look like her grades were much better than they are. Immediately worrying about what the neighbours will think, Yoshiko finds it hard to deal with the embarrassment of her husband and teenage daughter going door-to-door and doing menial work in the community, especially when she overhears the snickers of gossipy housewives in the local supermarket. For Yoshiko, whose sense of self worth was bound up with having a successful husband employed at a top tier company, Nariyuki’s sudden lurch towards individual freedom has destabilised her entire existence. Her world ceases to make sense.

Yoshiko’s sense of displacement is deepened when the fledgling company’s second job offer comes from Nariyuki’s ex-wife. Beniko (Hitomi Takahashi) left Nariyuki for another man because she failed to appreciate Nariyuki’s gentle charms and he was too mild mannered to fight for his wife even if he loved her deeply. What’s more, Nariyuki’s unconventional approach to life has earned him a spot in the papers and brought the family back to the attention of Sugina’s father, Ejima (Akira Onodera).

Early on Nariyuki states that life’s true radiance is only visible through suffering and later says that pain and suffering are essential parts of human existence. Nariyuki, now making a stand for himself for the first time in his life, remains philosophical in the face of hardship though perhaps has more faith in Yoshiko’s ability to follow him down this untrodden path than was wise. As a son and then a husband, Nariyuki may be a methodical sort but he’s unused to the idea of caring for himself as his comical attempts at doing the housework show. After almost burning the house down several times, Nariyuki does indeed figure out an efficient way of managing the household chores and seeing to Sugina’s education whilst also allowing his wife become the family breadwinner. However, Yoshiko’s new line of work is one she finds both unpleasant and degrading and she probably hoped that Nariyuki would strenuously try to stop her doing it so it’s not quite as much of a progressive approach as might be hoped.

After countless setbacks, humorous adventures, and a major fire Nariyuki’s enterprise begins to catch on. Brought together in shared crisis, the family unit only becomes stronger and more committed to their shared destinies. In fact, the family expands as Sugina rebuilds her relationship with birth father and even gains a new aunt figure in the form of her step-father’s youthful ex-wife. When you love what you do everyday is a holiday, and Sugina’s path, unconventional as it is, is one that leads her into the sunlight guided by Nariyuki’s oddly philosophical wisdom.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy.

After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy. The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as

The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as  The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics.

The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics. Adolescent romance is complicated enough at the best of times but the barriers are ever higher if you happen to be gay in a less than tolerant society. Ryosuke Hashiguchi’s second feature Like Grains of Sand (渚のシンドバッド, Nagisa no Sinbad) takes a slight step back in time from

Adolescent romance is complicated enough at the best of times but the barriers are ever higher if you happen to be gay in a less than tolerant society. Ryosuke Hashiguchi’s second feature Like Grains of Sand (渚のシンドバッド, Nagisa no Sinbad) takes a slight step back in time from  Ryosuke Hashiguchi’s debut feature A Touch of Fever (二十才の微熱, Hatachi no Binetsu) proved a surprise box office hit in Japan and is also credited for helping to bring male homosexuality into the mainstream. A no-budget movie shot on 16mm, A Touch of Fever is the story of two ordinary boys each going about their everyday lives whilst also beginning to understand themselves in terms of their sexualities, mirroring each other perfectly in their inner confusion.

Ryosuke Hashiguchi’s debut feature A Touch of Fever (二十才の微熱, Hatachi no Binetsu) proved a surprise box office hit in Japan and is also credited for helping to bring male homosexuality into the mainstream. A no-budget movie shot on 16mm, A Touch of Fever is the story of two ordinary boys each going about their everyday lives whilst also beginning to understand themselves in terms of their sexualities, mirroring each other perfectly in their inner confusion. Yoshitmitsu Morita tackled many different genres during his extremely varied career taking in everything from absurd social satire to teen idol vehicles and high art films. 1997’s Lost Paradise (失楽園, Shitsurakuen) again finds him in the art house realm as he prepares a tastefully erotic exploration of middle aged amour fou. Based on the bestselling novel by Junichi Watanabe, Lost Paradise also became a breakout box office hit as audiences were drawn by the tragic tale of doomed late love frustrated by societal expectations.

Yoshitmitsu Morita tackled many different genres during his extremely varied career taking in everything from absurd social satire to teen idol vehicles and high art films. 1997’s Lost Paradise (失楽園, Shitsurakuen) again finds him in the art house realm as he prepares a tastefully erotic exploration of middle aged amour fou. Based on the bestselling novel by Junichi Watanabe, Lost Paradise also became a breakout box office hit as audiences were drawn by the tragic tale of doomed late love frustrated by societal expectations. If you’re going on the run you might as well do it in style. Wait, that’s terrible advice isn’t it? Perhaps there’s something to be said for planning a cunning double bluff by becoming so flamboyant that everyone starts ignoring you out of a mild sense of embarrassment but that’s quite a risk for someone whose original gamble has so obviously gone massively wrong. An adaptation of a manga, Katsuhito Ishii’s debut feature Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl (鮫肌男と桃尻女, Samehada Otoko to Momojiri Onna) follows a mysterious criminal trying to head off the gang he just stole a bunch of money from whilst also accompanying a strange young girl, also on the run but from her perverted, hotel owning “uncle” who has also sent an equally eccentric hitman after the absconding pair with instructions to bring her back.

If you’re going on the run you might as well do it in style. Wait, that’s terrible advice isn’t it? Perhaps there’s something to be said for planning a cunning double bluff by becoming so flamboyant that everyone starts ignoring you out of a mild sense of embarrassment but that’s quite a risk for someone whose original gamble has so obviously gone massively wrong. An adaptation of a manga, Katsuhito Ishii’s debut feature Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl (鮫肌男と桃尻女, Samehada Otoko to Momojiri Onna) follows a mysterious criminal trying to head off the gang he just stole a bunch of money from whilst also accompanying a strange young girl, also on the run but from her perverted, hotel owning “uncle” who has also sent an equally eccentric hitman after the absconding pair with instructions to bring her back.

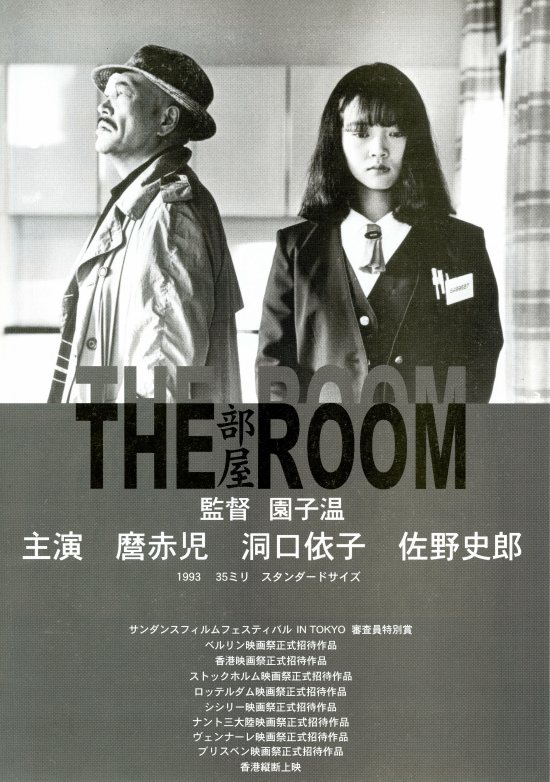

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent.

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent. Every once in a while an artist emerges whose work is so far ahead of its time that the audience of the day is unwilling to accept but generations to come will finally recognise for the achievement it represents. So it is for Sharaku – a young man whose abilities and ambitions are ruthlessly manipulated by those around him for their own gain. Brought to the screen by veteran new wave director Masahiro Shinoda, Sharaku (写楽) is an attempt to throw some light on the life of this mysterious historical figure who comes to symbolise, in many ways, the turbulence of his era.

Every once in a while an artist emerges whose work is so far ahead of its time that the audience of the day is unwilling to accept but generations to come will finally recognise for the achievement it represents. So it is for Sharaku – a young man whose abilities and ambitions are ruthlessly manipulated by those around him for their own gain. Brought to the screen by veteran new wave director Masahiro Shinoda, Sharaku (写楽) is an attempt to throw some light on the life of this mysterious historical figure who comes to symbolise, in many ways, the turbulence of his era.