Review of Chen Kaige’s 1993 masterpiece Farewell My Concubine (霸王别姬, Bàwáng Bié Jī) first published by UK Anime Network.

“Why does the concubine have to die?” Spanning 53 years of turbulent, mid twentieth century history, Farewell My Concubine is often regarded as the masterpiece of fifth generation director Chen Kaige and one of the films which finally brought Chinese cinema to global attention in the early 1990s. Neatly framing the famous Peking Opera as a symbol of its nation’s soul, the film centres on two young actors who find themselves at the mercy of forces far beyond their control.

Beginning in 1924, Douzi (later Cheng Dieyi) is sold to an acting troupe by his prostitute mother who can no longer care for him. The life in the theatre company is hard – the boys are taught the difficult skills necessary for performing the traditional art form through “physical reinforcement” where beatings and torturous treatment are the norm. Douzi is shunned by the other boys because of his haughty attitude and place of birth but eventually finds a friend in Shitou (later Duan Xiaolou) who would finally become the king to his concubine and a lifelong companion, for good or ill.

Time moves on and the pair become two of the foremost performers of their roles in their generation much in demand by fans of the Opera. However, personal and political events eventually intervene as Xiaolou decides to take a wife, Juxian – formerly a prostitute, and shortly after the Japanese reach the city. Coerced by various forces, Dieyi makes the decision to perform for the Japanese but Xiaolou refuses. After the Japanese have been defeated Dieyi is tried as a traitor though both Xiaolou and Juxian come to his rescue. The pair run in to trouble again during the civil war, but worse is to come during the “Cultural Revolution” in which the ancient art of Peking Opera itself is denounced as a bourgeois distraction and its practitioners forced into a very public self criticism conducted in full costume with their precious props burned in front of them. It’s not just artifice which goes up in smoke either as the two are browbeaten into betraying each other’s deepest, darkest secrets.

Farewell My Concubine is a story of tragic betrayal. Dieyi, placed in the role of the concubine without very much say in the matter, is betrayed by everyone at every turn. Abandoned by his mother, more or less prostituted by the theatre company who knowingly send him to an important man who molests him after a performance and then expect him to undergo the same thing again as a grown man when an important patron of the arts comes to visit, rejected by Xiaolou when he decides to marry a prostitute and periodically retires from the opera, and finally betrayed by having his “scandalous” secret revealed in the middle of a public square. He’s a diva and a narcissist, selfish in the extreme, but he lives only for his art, naively ignorant of all political concerns.

Dieyi doesn’t just perform Peking Opera, he lives it. His world is one of grand emotions and an unreal romanticism. Xiaolou by contrast is much more pragmatic, he just wants to do his job and live quietly. On the other hand, Xiaolou refuses to perform for the Japanese (the correct decision in the long run), and has a fierce temper and ironic personality which often get him into just as much trouble as Dieyi’s affected persona. The two are as bound and as powerless as the King and the Concubine, each doomed and unable to save each other from the inevitable suffering dealt them by the historical circumstances of their era.

The climax of the opera Farewell My Concubine comes as the once powerful king is finally defeated and forced to flee with only his noble steed left beside him. He begs his beloved concubine to run to sanctuary but such is her love for him that she refuses and eventually commits suicide so that the king can escape unburdened by worry for her safety. Dieyi’s tragedy is that he lives the role of the concubine in real life. Unlike Xiaolou, his romanticism (and a not insignificant amount of opium) cloud his view of the world as it really is.

It’s not difficult to read Dieyi as a cipher for his nation which has also placed an ideal above the practical demands of real living people with individual emotions of their own. Farewell My Concubine ran into several problems with the Chinese censors who objected not only to the (actually quite subtle) homosexual themes, but also to the way China’s recent history was depicted. Later scenes including one involving a suicide in 1977, not to mention the sheer absurd horror of the Cultural Revolution are all things the censors would rather not acknowledge as events which took place after the birth of the glorious communist utopia but Farewell My Concubine is one of the first attempts to examine such a traumatic history with a detached eye.

Casting Peking Opera as the soul of China, Farewell My Concubine is the story of a nation betraying itself. Close to the end when Dieyi is asked about the new communist operas he says he finds them unconvincing and hollow in comparison to the opulence and grand emotions of the classical works. Something has been shed in this abnegation of self that sees the modern state attempting to erase its true nature by corrupting its very heart. Full of tragic inevitability and residual anger over the unacknowledged past, Farewell My Concubine is both a romantic melodrama of unrequited love and also a lament for an ancient culture seemingly intent on destroying itself from the ground up.

Farewell My Concubine is released on blu-ray in the UK by BFI on 21st March 2016.

Original US trailer (with annoying voice over):

Article 39 of Japan’s Penal Code states that a person cannot be held responsible for a crime if they are found to be “insane” though a person who commits a crime during a period of “diminished responsibility” can be held accountable and will receive a reduced sentence. Yoshimitsu Morita’s 1999 courtroom drama/psychological thriller Keiho (39 刑法第三十九条, 39 Keiho Dai Sanjukyu Jo) puts this very aspect of the law on trial. During this period (and still in 2016) Japan does nominally have the death penalty (though rarely practiced) and it is only right in a fair and humane society that those people whom the state deems as incapable of understanding the law should receive its protection and, if necessary, assistance. However, the law itself is also open to abuse and as it’s largely left to the discretion of the psychologists and lawyers, the judgement of sane or insane might be a matter of interpretation.

Article 39 of Japan’s Penal Code states that a person cannot be held responsible for a crime if they are found to be “insane” though a person who commits a crime during a period of “diminished responsibility” can be held accountable and will receive a reduced sentence. Yoshimitsu Morita’s 1999 courtroom drama/psychological thriller Keiho (39 刑法第三十九条, 39 Keiho Dai Sanjukyu Jo) puts this very aspect of the law on trial. During this period (and still in 2016) Japan does nominally have the death penalty (though rarely practiced) and it is only right in a fair and humane society that those people whom the state deems as incapable of understanding the law should receive its protection and, if necessary, assistance. However, the law itself is also open to abuse and as it’s largely left to the discretion of the psychologists and lawyers, the judgement of sane or insane might be a matter of interpretation.

Starting as he meant to go on, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s debut feature film is the story of two slackers, each aimlessly drifting through life without a sense of purpose or trajectory in sight. His humour here is even drier than in his later films and though the tone is predominantly sardonic, one can’t help feeling a little sorry for his hapless, lonely “heroes” trapped in their vacuous, empty lives.

Starting as he meant to go on, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s debut feature film is the story of two slackers, each aimlessly drifting through life without a sense of purpose or trajectory in sight. His humour here is even drier than in his later films and though the tone is predominantly sardonic, one can’t help feeling a little sorry for his hapless, lonely “heroes” trapped in their vacuous, empty lives. The late Ken Takakura is best remembered as cinema’s original hard man but when the occasion arose he could provoke the odd tear or two just the same. 1999’s Poppoya (鉄道員) directed by frequent collaborator Yasuo Furuhata sees him once again playing the tough guy with a battered heart only this time he’s an ageing station master of a small town in deepest snow country which was once a prosperous mining village but is now a rural backwater.

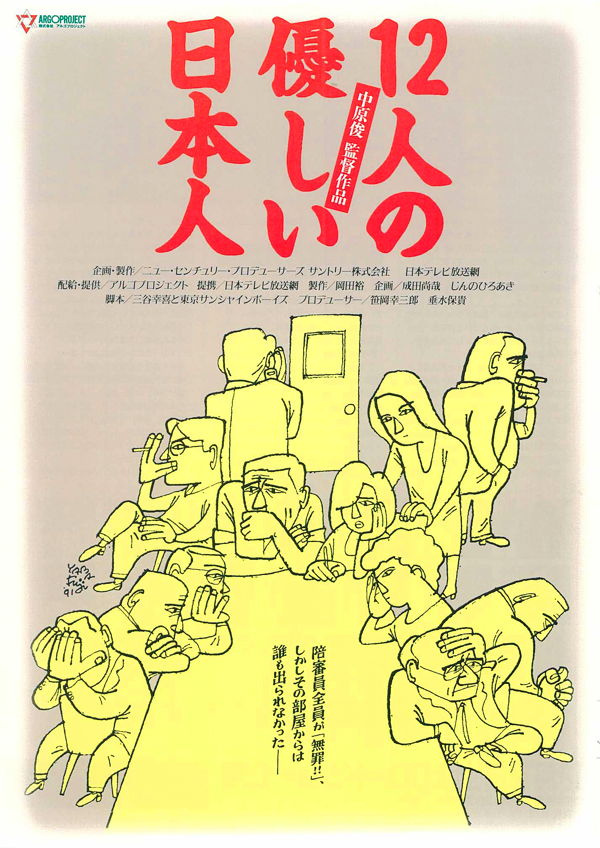

The late Ken Takakura is best remembered as cinema’s original hard man but when the occasion arose he could provoke the odd tear or two just the same. 1999’s Poppoya (鉄道員) directed by frequent collaborator Yasuo Furuhata sees him once again playing the tough guy with a battered heart only this time he’s an ageing station master of a small town in deepest snow country which was once a prosperous mining village but is now a rural backwater. As you might be able to tell from its title, Gentle 12 (12人の優しい日本人, Juninin no Yasashii Nihonjin) is a loose Japanese parody of the stage play 12 Angry Men notably filmed by Sidney Lumet back in 1957. The Japanese title literally translates as “12 Kindly Japanese Guys” and the film takes the same premise of twelve jurors debating the verdict in a murder case which was previously thought fairly straightforward. This time our jury is a little more balanced as it’s not just guys in the room and even the men are of a more diverse background.

As you might be able to tell from its title, Gentle 12 (12人の優しい日本人, Juninin no Yasashii Nihonjin) is a loose Japanese parody of the stage play 12 Angry Men notably filmed by Sidney Lumet back in 1957. The Japanese title literally translates as “12 Kindly Japanese Guys” and the film takes the same premise of twelve jurors debating the verdict in a murder case which was previously thought fairly straightforward. This time our jury is a little more balanced as it’s not just guys in the room and even the men are of a more diverse background.