A literal shaggy dog story, Jiang Jiachen’s Looking for Lucky (寻狗启事, Xún Gǒu Qǐshì) is not just the tale of one hapless young man’s attempt to regain his mentor’s approval in the form of his prize pooch, but of that same man’s desperation for a “lucky” break that will set him on a path to middle-class success without the need to debase himself through bribery. A melancholy exploration of the perils and pitfalls of youth in Modern China Jiang’s indie dramedy finds little to be optimistic about, save the faith that nature will run its course and perhaps you will end up where you’re supposed to be even if you have to go on a wild dog chase to get there.

A literal shaggy dog story, Jiang Jiachen’s Looking for Lucky (寻狗启事, Xún Gǒu Qǐshì) is not just the tale of one hapless young man’s attempt to regain his mentor’s approval in the form of his prize pooch, but of that same man’s desperation for a “lucky” break that will set him on a path to middle-class success without the need to debase himself through bribery. A melancholy exploration of the perils and pitfalls of youth in Modern China Jiang’s indie dramedy finds little to be optimistic about, save the faith that nature will run its course and perhaps you will end up where you’re supposed to be even if you have to go on a wild dog chase to get there.

Zhang Guangsheng (Ding Xinhe) is an ambitious grad student from a humble background. With graduation looming, he’s preoccupied about turning his educational investment into a solid job opportunity. Luckily he’s spent the last three years playing errand boy for his professor, Niu, who has all but promised him a cushy faculty job as long as he continues to play his cards right. Everything starts to go wrong when Guangsheng is asked to dog-sit while Niu is away and unwisely delegates the responsibility to his drunken grumpy father (Yu Hai) who loses him after the dog supposedly bites a stuck up little boy who was teasing him. Guangshang does his best to find the dog before Niu gets home, even succumbing to buying a new dog just in case, but all to no avail.

The reason Guangshang needs to find the dog isn’t just guilt and embarrassment at having potentially caused emotional distress to someone he respects, but because he knows that the failure to cope with this minor level of responsibility may ruin his relationship with Niu. Again, the relationship itself is not what’s important so much as what it can do for his career prospects. Guangshang is from a humble background and lacks the resources to buy his way to success as other young people often do – an endorsement from someone like Niu is his only chance to catapult himself into a steady middle-class life. Thus he’s spent the last three years bowing and scraping, debasing himself to be Niu’s go to guy and now it’s all going to out of the window thanks to his dad’s mistake.

A neurotic intellectual, Guangshang’s relationship with his polar opposite of a father is already difficult even before the dog incident. Guangshang’s dad is one of China’s many “laid off workers”, unceremoniously made redundant from a job for life as part the nation’s longterm economic modernisation. An embittered, angry man Guangshang’s dad quarrels with everything and everyone, sees scams everywhere, and has a much more cynical, world weary belief system than his kindhearted, idealistic son. The pair do, however, have something in common in their striving to live “independently” on their own skills alone. Abhorring the corruption of their society in which nothing is done fairly and money rules all, they each stubbornly refuse to give in and do things the “normal” way, not wanting the kind of success than can be bought.

Guangshang might be prepared to humiliate himself by playing servant, but he has his pride and doesn’t like seeing his poverty deployed as a weapon against him – especially by a “wealthy” friend who has looked at all the files and “admires” Guangshang’s perseverance, nor by his mother and her immensely calm second husband who are only too happy to give him the money to “buy” a university position, but not to help his father when he gets himself into trouble (again). Yet what Guangshang eventually discovers is that he has not lived as far from the systems of corruption as he had assumed – a realisation that both bolsters and destroys his sense of self confidence as he begins to understand his father’s true feelings while his sense of security in his academic prowess threatens to implode.

Everybody wants something – usually money, sometimes advancement, but no one can be trusted and nothing is done for free out of the goodness of one’s heart. Guangshang, without money, pays in other ways and then is cruelly undercut by someone else forced to do the same only in a sadder, even more morally dubious fashion as Niu is exposed for the corrupt figure he really is despite his “scholarly” standing. “Let nature take its course” Guangshang is urged by a fortuneteller he turns to in desperation for an indication of the whereabouts of his missing dog, but Guangshang is a young man in a hurry and has no time to wait around for a less than enticing fate. Yet for all the suffering and petty disappointments, justice is eventually served, patience rewarded and the virtuous victorious. Maybe it does all come right in the end, so long as you’ve the patience to let the dog off the leash and enough faith to see him safely home.

Looking for Lucky was screened as part of the 2018 New York Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

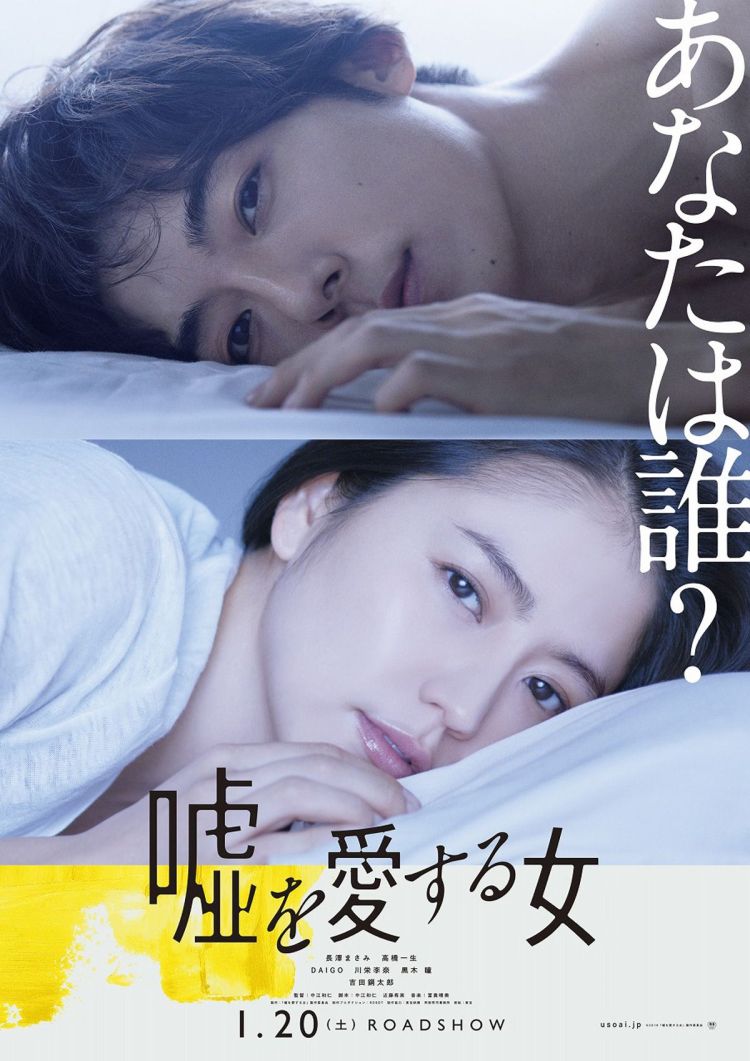

How well do you really know the people with whom you share your life? Or, perhaps, how honest have you really been with those closest you? Inspired by a notorious newspaper article, The Lies She Loved (嘘を愛する女, Uso wo Aisuru Onna) has a few hard questions to ask about the nature of modern relationships and the secrets which often lie at their hearts. Yet the message is perhaps that there are different kinds of truths and the literal may be among the least important of them. The salient message is that consideration for the feelings of others and a willingness to share the burden of being alive are the only real paths towards a fulfilling existence.

How well do you really know the people with whom you share your life? Or, perhaps, how honest have you really been with those closest you? Inspired by a notorious newspaper article, The Lies She Loved (嘘を愛する女, Uso wo Aisuru Onna) has a few hard questions to ask about the nature of modern relationships and the secrets which often lie at their hearts. Yet the message is perhaps that there are different kinds of truths and the literal may be among the least important of them. The salient message is that consideration for the feelings of others and a willingness to share the burden of being alive are the only real paths towards a fulfilling existence.