It’s a strange thing to say, but no two people can ever know the same person in the same way. We’re all, in a sense, in between each other, only holding some of the pieces in the puzzle of other people’s lives. Lee Dong-eun’s debut feature, In Between Seasons (환절기, Hwanjeolgi), is the story of three people who love each other deeply but find that love tested by secrets, resentments, cultural taboos and a kind of unwilling selfishness.

It’s a strange thing to say, but no two people can ever know the same person in the same way. We’re all, in a sense, in between each other, only holding some of the pieces in the puzzle of other people’s lives. Lee Dong-eun’s debut feature, In Between Seasons (환절기, Hwanjeolgi), is the story of three people who love each other deeply but find that love tested by secrets, resentments, cultural taboos and a kind of unwilling selfishness.

Beginning at the mid-point with a violent car crash, Lee then flashes back four years perviously as Soo-hyun (Ji Yun-ho) introduces his new friend, Yong-joon (Lee Won-gun), to his mother, Mi-keyong (Bae Jong-ok). Soo-hyun’s father has been living abroad in the Philippines for some time and so it’s just the two of them, while Yong-joon’s uneasy sadness is easily explained away on learning that his mother recently committed suicide. Thankful that her son has finally made a friend and feeling sorry for Yong-joon, Mi-kyeong practically adopts him, welcoming him into their home where he becomes a more or less permanent fixture until the boys leave high school.

Four years later, Soo-hyun and Yong-joon are both involved in the car crash which opened the film. Yong-joon has only minor injuries, but Soo-hyun is in a deep coma with possibly irreversible brain damage. It’s at this point that Mi-kyeong finally realises the true nature of the relationship between her son and his friend – that they had been close, inseparable lovers, and that she had never known about it.

When Mi-kyeong receives the phone call to tell her that her son has been in an accident, her friends are joking about their own terrible boys. As one puts it, there are three things a son should never tell his mother – the first being that he’s going to become a monk, the second that he’s going to buy a motorcycle, and the third is something so terrible they can’t even say it out loud. Mi-kyeong’s reaction to discovering her son is gay is predictably negative. Despite having cared for Yong-joon as a mother all these years, she can no longer bear to look at him and tells him on no uncertain terms not come visiting again. Yet for all that her reaction is only half informed by prevailing cultural norms, it’s not so much shame or disgust that she feels as resentment. Here is a man who loves her son, only differently than she does, and therefore knows things about him she never will or could hope to. She is forced to realise that the image she had of Soo-hyun is largely self created and the realisation leaves her feeling betrayed, let down, and rejected.

Both Mi-kyeong and Yong-joon ask the question “What have I done wrong?” at several points in the film – Yong-joon most notably when he’s rejected by Mi-kyeong without explanation, and Mi-kyeong when she’s considering why she’s not been included in the wedding plans for a friend’s daughter. Both Mi-kyeong and Yong-joon are made to feel excluded because they make people “uncomfortable” – Yong-joon because of his sexuality (which he continues to keep secret from his colleagues at work), and Mi-kyeong because of her grief-stricken purgatory. No one quite knows what to say to her, or wants to think about the pain and suffering she must be experiencing. They may claim they don’t want to upset her with something as joyous as a wedding but really it’s more that they don’t want her sadness to cast a shadow over the occasion.

Gradually the ice begins to thaw as Mi-kyeong allows Yong-joon back into her life again even if she can’t quite come to terms with his feelings for her son, describing him as a “friend” and embarrassed by his presence in front of her sister and other visitors. Soo-hyun’s illness and subsequent dependency ironically enough push Mi-kyeong towards the kind of independence she had always rejected – finally learning to drive, sorting out her difficult marital circumstances, and starting to live for herself as well as for her son. Yong-joon remains stubborn and in love, refusing to be shut out of Soo-hyun’s life even whilst considering the best way to live his own. Beautifully composed in all senses of the word, Lee’s frames are filled with anxious longing and inexpressible sadness tempered with occasional joy. Too astute to opt for a crowd pleasing victory, Lee ends on a more realistic note of hopeful ambiguity with anxiety seemingly exorcised and replaced with tranquil, easy sleep.

Screened at the London Korean Film Festival 2017. In Between Seasons will also be screened at the Broadway Cinema in Nottingham on 11th November.

Trailer/behind the scenes EPK (no subtitles)

Interview with director Lee Dong-eun conducted during the film’s screening at the Busan International Film Festival in 2016.

Hiroya Oku’s long running manga series Gantz has already been adapted as a TV anime as well as two very successful live action films from Shinsuke Sato. Gantz:O (ガンツ:オー) is the first feature length animated treatment of the series and makes use of 3D CGI and motion capture for a hyperrealistic approach to alien killing action. “O” for Osaka rather than “0” for zero, the movie is inspired by the spin-off Osaka arc of the manga shifting the action south from the regular setting of central Tokyo.

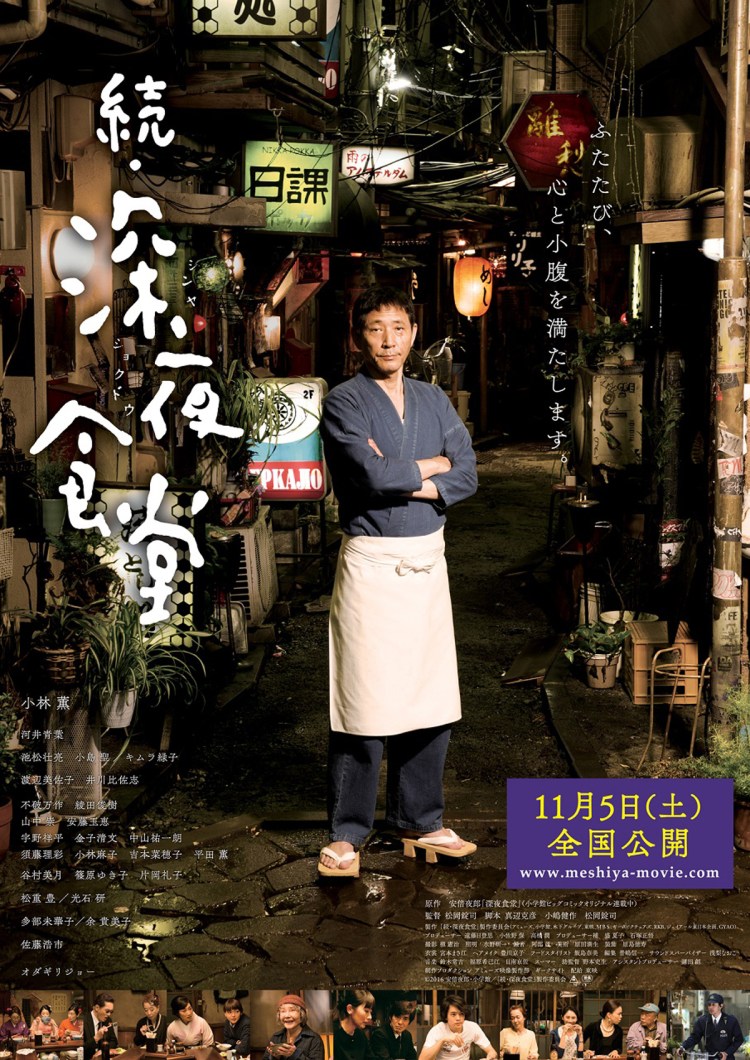

Hiroya Oku’s long running manga series Gantz has already been adapted as a TV anime as well as two very successful live action films from Shinsuke Sato. Gantz:O (ガンツ:オー) is the first feature length animated treatment of the series and makes use of 3D CGI and motion capture for a hyperrealistic approach to alien killing action. “O” for Osaka rather than “0” for zero, the movie is inspired by the spin-off Osaka arc of the manga shifting the action south from the regular setting of central Tokyo. The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the

The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the  In a time of crisis, the populace looks to the government to take action and save the innocent from danger. A government, however, is often forced to consider the problem from a different angle – not simply saving lives but how their success or failure, decision-making process, and ability to handle the situation will be viewed by the electorate the next time they are asked who best deserves their faith and respect. Pandora (판도라) arrives at a time of particularly strained relations between the state and its people during which faith in the ruling elite is at an all time low following a tragic disaster badly mishandled and seemingly aided by the government’s failure to ensure public safety. Faced with an encroaching nuclear disaster to which their own failure to heed the warnings has played no small part, Pandora’s officials are left in a difficult position tasked with the dilemma of sacrificing a small town to save a nation or accepting their responsibility to their citizens as named individuals. Unsurprisingly, they are far from united in their final decision.

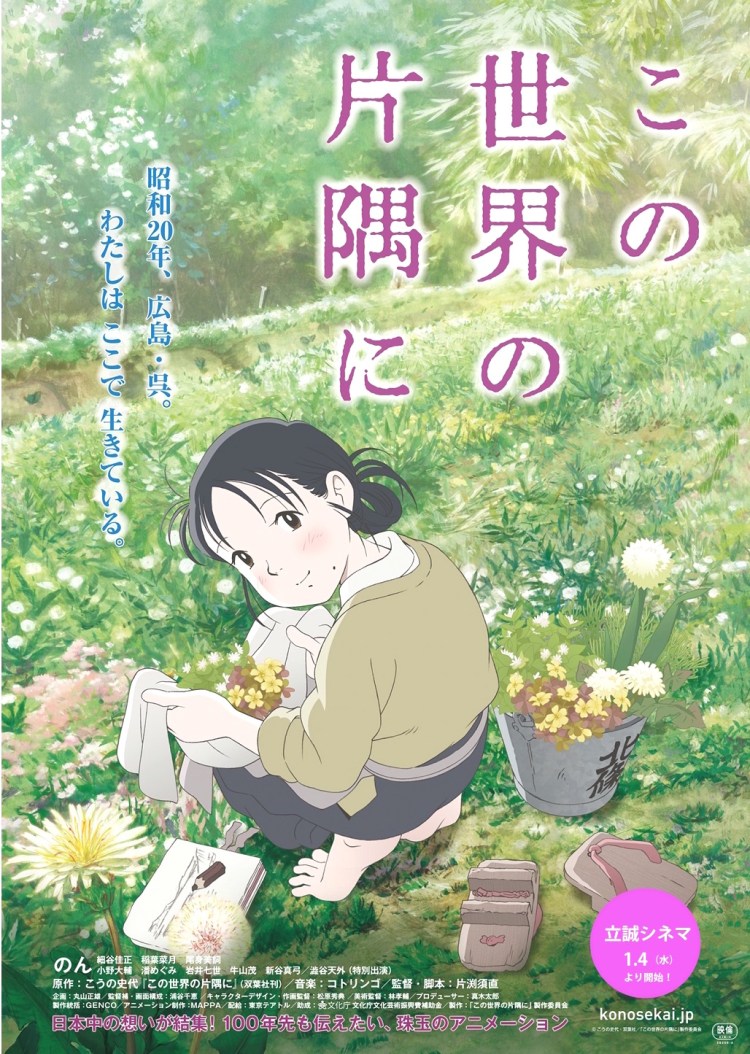

In a time of crisis, the populace looks to the government to take action and save the innocent from danger. A government, however, is often forced to consider the problem from a different angle – not simply saving lives but how their success or failure, decision-making process, and ability to handle the situation will be viewed by the electorate the next time they are asked who best deserves their faith and respect. Pandora (판도라) arrives at a time of particularly strained relations between the state and its people during which faith in the ruling elite is at an all time low following a tragic disaster badly mishandled and seemingly aided by the government’s failure to ensure public safety. Faced with an encroaching nuclear disaster to which their own failure to heed the warnings has played no small part, Pandora’s officials are left in a difficult position tasked with the dilemma of sacrificing a small town to save a nation or accepting their responsibility to their citizens as named individuals. Unsurprisingly, they are far from united in their final decision. Depictions of wartime and the privation of the immediate post-war period in Japanese cinema run the gamut from kind hearted people helping each other through straitened times, to tales of amorality and despair as black-marketeers and unscrupulous crooks take advantage of the vulnerable and the desperate. In This Corner of the World (この世界の片隅に, Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni), adapted from the manga by Hiroshima native Fumiyo Kouno, is very much of the former variety as its dreamy, fantasy-prone heroine is dragged into a very real nightmare with the frontier drawing ever closer and the threat of death from the skies ever more present but manages to preserve something of herself even in such difficult times.

Depictions of wartime and the privation of the immediate post-war period in Japanese cinema run the gamut from kind hearted people helping each other through straitened times, to tales of amorality and despair as black-marketeers and unscrupulous crooks take advantage of the vulnerable and the desperate. In This Corner of the World (この世界の片隅に, Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni), adapted from the manga by Hiroshima native Fumiyo Kouno, is very much of the former variety as its dreamy, fantasy-prone heroine is dragged into a very real nightmare with the frontier drawing ever closer and the threat of death from the skies ever more present but manages to preserve something of herself even in such difficult times.

Anocha Suwichakornpong’s second feature, By the Time it Gets Dark (ดาวคะนอง.Dao Khanong), bills itself as an exploration of a traumatic moment from the recent past but quickly subverts this conceit for a wider meditation on the veracity of cinema. Beginning in a manner typical of indie-leaning Thai films, Anocha gently undercuts herself as her images prism into their separate “realities”, informing and commenting on each other but perhaps not fully interacting. The Thammasat University student massacre of 1976 is the dark genesis of this fracturing future, but it’s also in the process of becoming a collective legend, cementing a “historical truth” as cultural currency even whilst expunged from the history books, leaving its young lost in a black hole of memory from which they are powerless to emerge.

Anocha Suwichakornpong’s second feature, By the Time it Gets Dark (ดาวคะนอง.Dao Khanong), bills itself as an exploration of a traumatic moment from the recent past but quickly subverts this conceit for a wider meditation on the veracity of cinema. Beginning in a manner typical of indie-leaning Thai films, Anocha gently undercuts herself as her images prism into their separate “realities”, informing and commenting on each other but perhaps not fully interacting. The Thammasat University student massacre of 1976 is the dark genesis of this fracturing future, but it’s also in the process of becoming a collective legend, cementing a “historical truth” as cultural currency even whilst expunged from the history books, leaving its young lost in a black hole of memory from which they are powerless to emerge. Kanae Minato is known for her hard-hitting crime stories from Confessions to

Kanae Minato is known for her hard-hitting crime stories from Confessions to  What would you give to live another day? What did you give to live this day? What did you take? Adapting the novel by Genki Kawamura, Akira Nagai takes a step back from the broad comedy of

What would you give to live another day? What did you give to live this day? What did you take? Adapting the novel by Genki Kawamura, Akira Nagai takes a step back from the broad comedy of