History books make for the grimmest reading, subjective as they often are. Science fiction can rarely improve upon the already existing evidence of humanity’s dark side, but Genocidal Organ (虐殺器官, Gyakusatsu Kikan) has good go anyway, extrapolating a long line of political manipulations into the near future which neatly straddles a utopian/dystopian divide. Plagued by production delays and studio bankruptcy, Genocidal Organ is the third of three films adapted from the novels of late sci-fi author Project Itoh, arriving nearly two years after previous instalments Harmony and Empire of Corpses. Sadly, its message has only become more timely as the world finds itself on the brink of a geo-political recalibration where fear and division rule the roost.

History books make for the grimmest reading, subjective as they often are. Science fiction can rarely improve upon the already existing evidence of humanity’s dark side, but Genocidal Organ (虐殺器官, Gyakusatsu Kikan) has good go anyway, extrapolating a long line of political manipulations into the near future which neatly straddles a utopian/dystopian divide. Plagued by production delays and studio bankruptcy, Genocidal Organ is the third of three films adapted from the novels of late sci-fi author Project Itoh, arriving nearly two years after previous instalments Harmony and Empire of Corpses. Sadly, its message has only become more timely as the world finds itself on the brink of a geo-political recalibration where fear and division rule the roost.

Set in 2022, the world of Genocidal Organ is one of intense “security”. Following the detonation of a nuclear bomb in Sarajevo in 2017, developed nations have once again become jumpy. As the world weary narrative voice over informs us, Americans have sacrificed their freedoms for an illusion of safety which decreases the burden of living under the threat of terrorism. This brave new world is a surveillance state where citizens are chipped and monitored, even the simple act of buying pizza requires an identity check.

Less developed nations, however, have descended into a hellish cycle of internecine wars and large scale atrocities. American special forces have identified a pattern which puts one of their own, mysterious linguistics professor John Paul (Takahiro Sakurai), at the centre of a vast conspiracy. Army Intelligence officer Clavis Shepherd (Yuichi Nakamura) is despatched to track the master criminal down through his sometime girlfriend Lucia (Sanae Kobayashi), a Czech national and former MIT linguistics researcher now teaching Czech to foreigners in Prague.

Clavis, like the best film noir heroes, finds himself falling down a rabbit hole into an increasingly uncertain world. A top soldier, he has been “engineered” to decrease emotionality and limit pain response to make him a “better” soldier. His world is first shaken when one of his comrades goes rogue, kills a valuable mark, and then turns a gun on him. The top brass blame PTSD but not only that, PTSD that was in fact induced by the very processes the soldiers undergo to ensure than PTSD is impossible. He has always believed that his actions, and those of his superiors have been for the greater good, but he has rarely stopped to think what that greater good may be.

Clavis’ missions see him jumping into a coffin-like landing pod and parachuting into street battles in which many of the combatants are children who have been drugged “to make them better soldiers”. Just as you’re starting to wonder who exactly is perpetrating the genocide, Clavis is asked the relevant question by a captive John. He replies that it’s just his job. John reminds Clavis that that particular justification has a long and terrifying history and so perhaps he ought to ask himself why he chooses to do this particular job and do it so blindly.

John’s big theory is that violence has its own grammar, a secret code buried in language which can be engineered to provoke political instability but then conveniently contained within its own language group. Essentially, he posits the idea of sicking the “terrorists” onto each other and letting them fight it out amongst themselves in those far off places which no one really cares about. The citizens of the developed world might frown at their morning papers, but they’ll soon file it under “terrible things happening far away” and go back to enjoying their lives of peace and security. John’s plan, he claims, is the opposite of vengeance, a means of keeping his side safe by ensuring that the terrible things stay far away, contained.

The “genocidal organ” is the heart hardened towards the suffering of others. John has some grand theories about this, about the survival instinct, fear, suspicion and desperation, but he also has a few on the trade offs between freedom and security. Itoh’s vision is bleak, and the prognosis bleaker but its logic cannot be denied, even if its execution is occasionally imperfect.

Currently on limited theatrical release throughout the UK courtesy of All the Anime.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard is more about the passing of an era and the fates of those who fail to swim the tides of history than it is about transience and the ever-present tragedy of the death of every moment, but still there is a commonality in the symbolism. Shun Nakahara’s The Cherry Orchard (櫻の園, Sakura no Sono) is not an adaptation of Chekhov’s play but of Akimi Yoshida’s popular 1980s shojo manga which centres on a drama group at an all girls high school. Alarm bells may be ringing, but Nakahara sidesteps the usual teen angst drama for a sensitively done coming of age tale as the girls face up to their liminal status and prepare to step forward into their own new era.

Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard is more about the passing of an era and the fates of those who fail to swim the tides of history than it is about transience and the ever-present tragedy of the death of every moment, but still there is a commonality in the symbolism. Shun Nakahara’s The Cherry Orchard (櫻の園, Sakura no Sono) is not an adaptation of Chekhov’s play but of Akimi Yoshida’s popular 1980s shojo manga which centres on a drama group at an all girls high school. Alarm bells may be ringing, but Nakahara sidesteps the usual teen angst drama for a sensitively done coming of age tale as the girls face up to their liminal status and prepare to step forward into their own new era. Absolute power corrupts absolutely, but such power is often a matter more of faith than actuality. Coming at an interesting point in time, Han Jae-rim’s The King (더 킹) charts twenty years of Korean history, stopping just short of its present in which a president was deposed by peaceful, democratic means following accusations of corruption. The legal system, as depicted in Korean cinema, is rarely fair or just but The King seems to hint at a broader root cause which transcends personal greed or ambition in an essential brotherhood of dishonour between men, bound by shared treacheries but forever divided by looming betrayal.

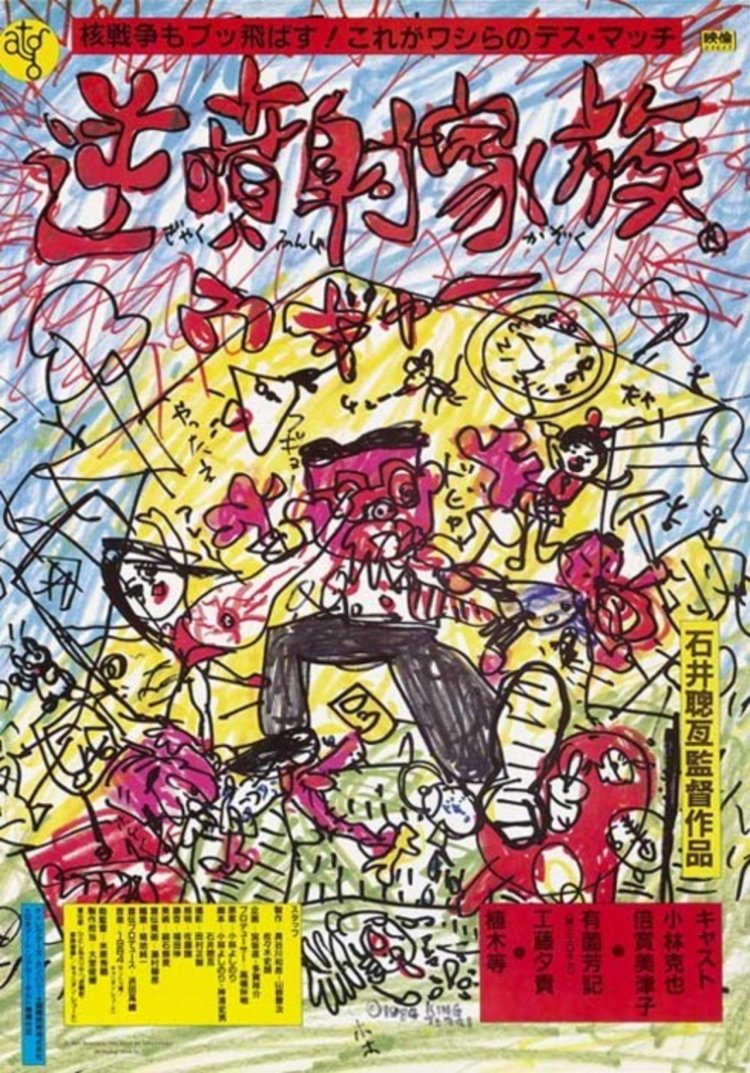

Absolute power corrupts absolutely, but such power is often a matter more of faith than actuality. Coming at an interesting point in time, Han Jae-rim’s The King (더 킹) charts twenty years of Korean history, stopping just short of its present in which a president was deposed by peaceful, democratic means following accusations of corruption. The legal system, as depicted in Korean cinema, is rarely fair or just but The King seems to hint at a broader root cause which transcends personal greed or ambition in an essential brotherhood of dishonour between men, bound by shared treacheries but forever divided by looming betrayal. The family drama went through something of a transformation at the beginning of the 1980s. Gone are the picturesque, sometimes melancholy evocations of the transience of family life, these families are fake, dysfunctional, or unreliable even if trying their best. Morita’s

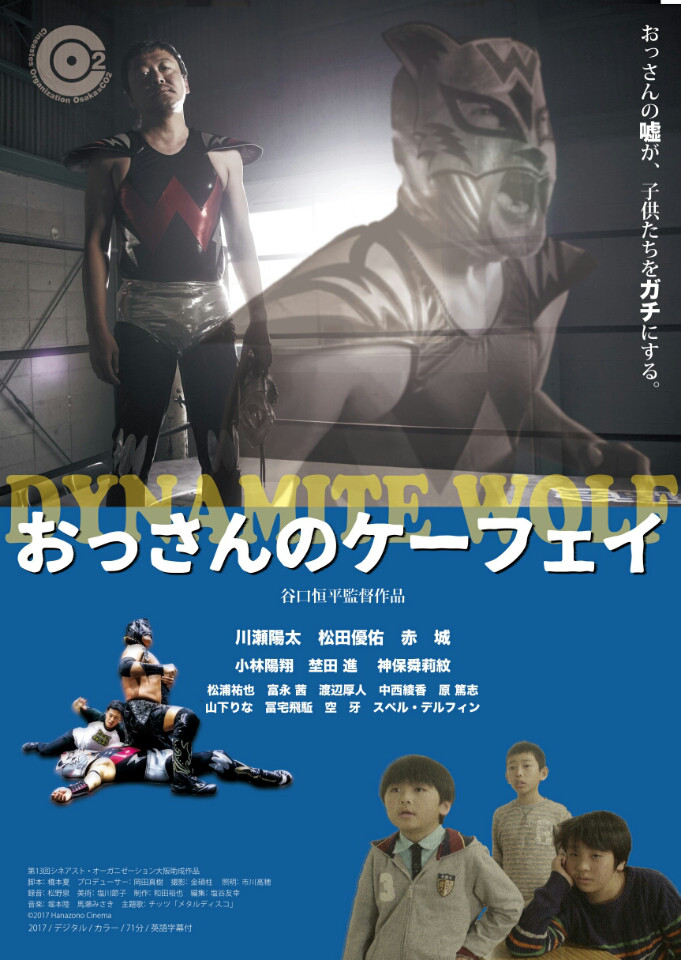

The family drama went through something of a transformation at the beginning of the 1980s. Gone are the picturesque, sometimes melancholy evocations of the transience of family life, these families are fake, dysfunctional, or unreliable even if trying their best. Morita’s  Back in the day, lucha libre-style wrestling was hugely popular in Japan. Tiger Mask, a manga set in the world of Japanese pro-wrestling remains a firm favourite and its eponymous hero has also become a byword for altruistic philanthropy as well-meaning anonymous donors donate expensive gifts such as Japanese school backpacks to orphanages in Tiger Mask’s name. Sadly, pro-wrestling is no longer as high-profile as it once was and has left mainstream television screens far behind even if it still maintains a small but dedicated fanbase. Kohei Taniguchi’s Dynamite Wolf (おっさんのケーフェイ, Ossan no Kefei) is out to change all that by shining a spotlight on this almost forgotten phenomenon of crazy outfits, killer moves, and camp showmanship.

Back in the day, lucha libre-style wrestling was hugely popular in Japan. Tiger Mask, a manga set in the world of Japanese pro-wrestling remains a firm favourite and its eponymous hero has also become a byword for altruistic philanthropy as well-meaning anonymous donors donate expensive gifts such as Japanese school backpacks to orphanages in Tiger Mask’s name. Sadly, pro-wrestling is no longer as high-profile as it once was and has left mainstream television screens far behind even if it still maintains a small but dedicated fanbase. Kohei Taniguchi’s Dynamite Wolf (おっさんのケーフェイ, Ossan no Kefei) is out to change all that by shining a spotlight on this almost forgotten phenomenon of crazy outfits, killer moves, and camp showmanship.

Taiwan and Japan have a complicated history, but in SABU’s latest slice of cross-cultural interplay each place becomes a kind of refuge from the other. Working largely in Mandarin and with Taiwanese star Chang Chen, SABU returns to a familiar story – the lonely hitman tempted by a normal family life filled with peace and simplicity only to have his dreams taken from him by the spectre of his past. Only this time it isn’t just his past but that of others too. Despite the melancholy air, Mr. Long (ミスター・ロン) is a testament to the power of simple human kindness but also a condemnation of underworld cruelty and its vicelike grip on all who enter its grasp.

Taiwan and Japan have a complicated history, but in SABU’s latest slice of cross-cultural interplay each place becomes a kind of refuge from the other. Working largely in Mandarin and with Taiwanese star Chang Chen, SABU returns to a familiar story – the lonely hitman tempted by a normal family life filled with peace and simplicity only to have his dreams taken from him by the spectre of his past. Only this time it isn’t just his past but that of others too. Despite the melancholy air, Mr. Long (ミスター・ロン) is a testament to the power of simple human kindness but also a condemnation of underworld cruelty and its vicelike grip on all who enter its grasp.

Parks are a common feature of modern city life – a stretch of green among the grey, but it’s important to remember that there has not always been such beautiful shared space set aside for public use. Natsuki Seta’s light and breezy youth comedy, Parks (PARKS パークス), was commissioned in celebration of the centenary of the Tokyo park where the majority of the action takes place, Inokashira. Mixing early Godardian whimsy with new wave voice over and the kind of innocent adventure not seen since the Kadokawa idol days, Parks is a sometimes melancholy, wistful tribute to a place where chance meetings can define lifetimes as well as to brief yet memorable summers spent with gone but not forgotten friends doing something which seems important but which in retrospect may be trivial.

Parks are a common feature of modern city life – a stretch of green among the grey, but it’s important to remember that there has not always been such beautiful shared space set aside for public use. Natsuki Seta’s light and breezy youth comedy, Parks (PARKS パークス), was commissioned in celebration of the centenary of the Tokyo park where the majority of the action takes place, Inokashira. Mixing early Godardian whimsy with new wave voice over and the kind of innocent adventure not seen since the Kadokawa idol days, Parks is a sometimes melancholy, wistful tribute to a place where chance meetings can define lifetimes as well as to brief yet memorable summers spent with gone but not forgotten friends doing something which seems important but which in retrospect may be trivial.

Towards the end of the 60s and faced with the same problems as any other studio of the day – namely declining receipts as cinema audiences embraced television, Nikkatsu decided to spice up their already racy youth orientated output with a steady stream of sex and violence. The Roman Porno line took a loftier approach to the “pink film” – mainstream softcore pornography played in dedicated cinemas and created to a specific formula, by putting the resources of a bigger studio behind it with greater production values and acting talent. 40 years on Roman Porno is back. Kazuya Shiraishi’s Dawn of the Felines (牝猫たち, Mesunekotachi) takes inspiration from Night of the Felines by the Roman Porno master Noboru Tanaka but where Tanaka’s film is a raucous comedy following the humorous adventures of its three working girl protagonists, Shiraishi’s is a much less joyous affair as he casts his three lonely heroines adrift in Tokyo’s red light district.

Towards the end of the 60s and faced with the same problems as any other studio of the day – namely declining receipts as cinema audiences embraced television, Nikkatsu decided to spice up their already racy youth orientated output with a steady stream of sex and violence. The Roman Porno line took a loftier approach to the “pink film” – mainstream softcore pornography played in dedicated cinemas and created to a specific formula, by putting the resources of a bigger studio behind it with greater production values and acting talent. 40 years on Roman Porno is back. Kazuya Shiraishi’s Dawn of the Felines (牝猫たち, Mesunekotachi) takes inspiration from Night of the Felines by the Roman Porno master Noboru Tanaka but where Tanaka’s film is a raucous comedy following the humorous adventures of its three working girl protagonists, Shiraishi’s is a much less joyous affair as he casts his three lonely heroines adrift in Tokyo’s red light district.

Learning to love Tokyo is a kind of suicide, according to the heroine of Yuya Ishii’s love/hate letter to the Japanese capital, The Tokyo Night Sky is Always the Densest Shade of Blue (夜空はいつでも最高密度の青色だ, Yozora wa Itsudemo Saiko Mitsudo no Aoiro da). This city is a mess of contradictions, a huge sprawling metropolis filled with the anonymous masses and at the same time so tiny you can find yourself running into the same people over and over again. Inspired by the poems of Tahi Saihate, The Tokyo Night Sky is at once a meditative contemplation of city life and an awkward love story between two lost souls who somehow find each other in its crowded backstreets.

Learning to love Tokyo is a kind of suicide, according to the heroine of Yuya Ishii’s love/hate letter to the Japanese capital, The Tokyo Night Sky is Always the Densest Shade of Blue (夜空はいつでも最高密度の青色だ, Yozora wa Itsudemo Saiko Mitsudo no Aoiro da). This city is a mess of contradictions, a huge sprawling metropolis filled with the anonymous masses and at the same time so tiny you can find yourself running into the same people over and over again. Inspired by the poems of Tahi Saihate, The Tokyo Night Sky is at once a meditative contemplation of city life and an awkward love story between two lost souls who somehow find each other in its crowded backstreets.

Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society.

Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society.