A studio director at Toei, Tadashi Sawashima is best remembered for his work in the studio’s ninkyo eiga genre – prewar tales of noble gangsters, and samurai movies but he also made the occasional foray into the world of musical drama, teaming up with top name singing star Hibari Misora on a few of her historical action musicals. In 1966’s Actress vs. Greedy Sharks (小判鮫 お役者仁義, Kobanzame Oyakusha Jingi) Hibari once again plays a dual role though this time her casting is entirely arbitrary and the visual similarity of the legit actress and the acrobatic outlaw is never explicitly remarked upon.

A studio director at Toei, Tadashi Sawashima is best remembered for his work in the studio’s ninkyo eiga genre – prewar tales of noble gangsters, and samurai movies but he also made the occasional foray into the world of musical drama, teaming up with top name singing star Hibari Misora on a few of her historical action musicals. In 1966’s Actress vs. Greedy Sharks (小判鮫 お役者仁義, Kobanzame Oyakusha Jingi) Hibari once again plays a dual role though this time her casting is entirely arbitrary and the visual similarity of the legit actress and the acrobatic outlaw is never explicitly remarked upon.

The action opens with Shichi (Hibari Misora), an acrobat and member of a Robin Hood style band of outlaws (they don’t so much give to the poor as “share” with the less fortunate) interrupting the plot of Yamitaro (Yoichi Hayashi) – a nobleman in disguise to pursue revenge against corrupt lord Doi (Eitaro Shindo) who exiled his father to Convict Island when he began to raise questions about judicial corruption. Meanwhile, Yuki (also played by Hibari) is a top stage actress who is plotting against Doi for sending her father to Convict Island 20 years previously on a trumped up charge. Just as the “tomboyish” Shichi is beginning to fall for the mysterious Yamitaro, he teams up with Yuki to pursue their mutual quests for revenge which has Shichi feeling (needlessly, as it turns out) betrayed and vengeful.

Once again, the samurai order is shown to be corrupt beyond redemption. Doi, a greedy lord, is planning to sell off his only daughter, Ran (Yumiko Nogawa), as a concubine to the shogun. Meanwhile, he is also engaging in a rice profiteering scheme in order to bolster his financial resources. He is also still misusing his influence, just as he did when he had Yuki’s father sent to prison and got rid of Yamitaro’s so he couldn’t expose him.

As in her other movies, Hibari cannot allow this corruption to continue and becomes a thorn in the side of authority. However, the situation this time around is further complicated by her double casting in which she plays two visually identical characters who are, nevertheless, entirely unrelated and the resemblance between them entirely unremarked upon. The “tomboyish” Shichi, apparently falling in love for the first time much to the confusion of herself and others who regarded her lack of traditional femininity as a barrier to romance, becomes awkwardly resentful of the graceful Yuki whose charms she assumes will sway the handsome Yamitaro. Shichi does not seem to consider a class barrier between herself and Yamitaro as a problem but fears his natural affinity with a woman she perceives as superior to herself in her refinement, yet Yuki proves herself as staunch a fighter as Shichi and just as feisty. She appears to have little romantic interest in Yamitaro even if she resents Shichi’s rather blunt instructions to back off, and aside from concentrating on her revenge, spends the rest of the film dealing with the rescue of Doi’s daughter Ran who has drawn inspiration from her stage performances to rebel against her cruel fate and father.

Ran is just another symptom of her father’s corruption in his obvious disregard for her feelings as he prepares to send her off as a concubine to buy himself influence with only the mild justification that her ascendence to the imperial court is an honour even if she will never be a wife, only one of many mistresses. Unlike Ran, Yuki and Shichi have managed to seize their own agency, living more or less independently and as freely as possible within the society they inhabit. Experiencing differing kinds of bad luck and betrayal, they find themselves at odds with each other yet on parallel paths despite their obvious dualities.

With less space for song, Hibari’s dual casting does at least offer twice the fight potential as the outlaw and the actress finally find themselves on the same side to tackle the persistent injustice of Edo era society as manifested in the corrupt Doi and his slimy cronies gearing up for the mass brawl finale in which the wronged take their revenge on the wicked lord by proving him a villain in the public square and earning themselves not a little social kudos in the process. All of which makes the strangely melancholy ending exiling one aspect of Hibari to the outer reaches somewhat uncomfortable but then it does provide an excuse for another song.

Hibari’s musical numbers

In the post-

In the post-

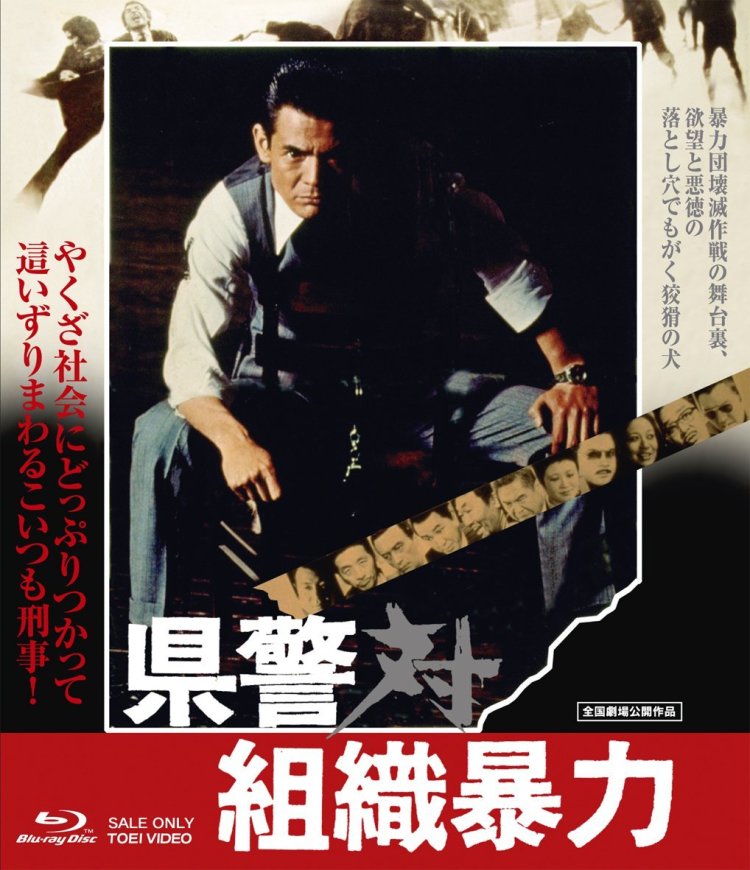

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first  Edogawa Rampo (a clever allusion to master of the gothic and detective story pioneer Edgar Allan Poe) has provided ample inspiration for many Japanese films from

Edogawa Rampo (a clever allusion to master of the gothic and detective story pioneer Edgar Allan Poe) has provided ample inspiration for many Japanese films from  It’s 1963 now and the chaos in the yakuza world is only increasing. However, with the Tokyo olympics only a year away and the economic conditions considerably improved the outlaw life is much less justifiable. The public are becoming increasingly intolerant of yakuza violence and the government is keen to clean up their image before the tourists arrive and so the police finally decide to do something about the organised crime problem. This is bad news for Hirono and his guys who are already still in the middle of their own yakuza style cold war.

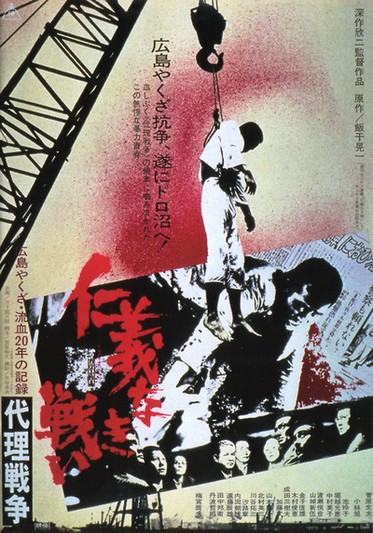

It’s 1963 now and the chaos in the yakuza world is only increasing. However, with the Tokyo olympics only a year away and the economic conditions considerably improved the outlaw life is much less justifiable. The public are becoming increasingly intolerant of yakuza violence and the government is keen to clean up their image before the tourists arrive and so the police finally decide to do something about the organised crime problem. This is bad news for Hirono and his guys who are already still in the middle of their own yakuza style cold war. Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly.

Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly. If you thought the story was over when Hirono walked out on the funeral at the end of

If you thought the story was over when Hirono walked out on the funeral at the end of