At the end of The Heroic Trio, the shadowy rise of authoritarianism seemed to have been beaten back. The three superwomen at the film’s centre had discovered joy and liberation in female solidarity and were committed to fighting injustice in a flawed but improving world. If Heroic Trio had been a defiant reaction to Handover anxiety, then sequel Executioners (現代豪俠傳) is its flip side shifting from the retro 40s Hong Kong as Gotham aesthetic to a post-apocalyptic nightmare world where nuclear disaster has normalised corporate fascist rule.

As Ching (Michelle Yeoh) explains in her opening voiceover, a nuclear attack has ruined the city contaminating its water and leaving ordinary citizens dependent on the Clear Water Corporation for safe drinking supplies and basic sanitation. The trio have been scattered, pushed back into the roles from which they escaped at the first film’s conclusion save perhaps for Ching who continues to serve a duplicitous authority but does so with clearer eyes and a humanitarian spirit driving a medicine truck to ensure those in need have access to healthcare. Chat (Maggie Cheung Man-Yuk) meanwhile has reverted to her cynical bandit lifestyle, hijacking water trucks mostly for her own gain but also ensuring the water gets to the needy. Tung (Anita Mui Yim-Fong) has abandoned her Wonder Woman persona on the insistence of her husband who is now a high ranking policeman with the military authority devoting herself to the role of the traditional housewife and mother to her daughter Cindy.

Though the women seem to have maintained their bond, Ching and Chat turning up for a Christmas celebration with Cindy, the political realities soon disrupt their friendship as they find themselves at odds with each other given their shifting allegiances. As in the first film, Chat has continued to accept work from dubious authority in the form of the Colonel including tracking down a man who embarrassed the police by firing a gun at a rally for a cult-like protest leader, Chung Hon (Takeshi Kaneshiro), only the gunman later turns out to be a patsy and Chat has unwittingly helped them bump off the voice of the people as an overture for a military coup. Ching is secretly working for responsible government trying to safeguard the President to prevent his assassination by the Colonel, but obviously cannot say very much about her mission arousing Tung’s suspicions that she may have been part of a plot to have her husband killed.

In any case, the true villain turns out to be a kind of Wonder Woman mirror image in that the mysterious Mr. Kim (Anthony Wong Chau-Sang), CEO of Clear Water Corporation, is a man who wears a mask to hide his scarred face and dresses like an 18th century aristocrat as if engaged in some kind of Man in the Iron Mask cosplay. Kim and the Colonel have been collaborating to engineer a military coup by deliberately restricting water supplies. The oblivious Chung Hon had unwittingly been Kim’s stooge, stoking up public resentment about the water situation to give the government an excuse for a crackdown and the Colonel to move. Chat’s path to redemption amounts to vindicating the faint hope that the water contamination was a hoax, which she eventually does by taking Cindy with her to smash the corporate dam and return the water to its rightful flow and the people of the city. But like the Evil Master, Kim does not die so easily turning up for a surprisingly hands on fight squaring off against the barely unified trio who are only just beginning to repair their friendships on coming to a fuller understanding of the reality of their circumstances.

They are all in a sense liberated, though less joyfully than in the first film and largely through violent loss. The good guys don’t always win and a fair few die while all the women can do is keep moving, fighting off one threat after another with few guarantees of success and not even each other to rely on. Where the first film had embraced a hopeful sense of comic camp, Executioners skews towards the nihilistic in its dystopian world of corporate overreach and increasing militarism in which the trio no longer trust each other and are each re-imprisoned inside their original cages from patriarchal social norms to capitalistic inhumanity and questionable loyalties with the only hopeful resolution resting on “the sincerity of our friendship” in a world which may be healing but is far from happy.

Executioners screened as part of this year’s San Diego Asian Film Festival.

“The Mad Monk” sounds like a great name for a creepy ghost, emerging robed and chanting from the shadows to make you fear for your mortal soul. Sadly, The Mad Monk (濟公, Jì Gōng) features only one “ghost”, but it might just be the cutest in cinema history. The second of Johnnie To’s Shaw Brothers collaborations with comedy star Stephen Chow is another wisecracking romp in which Chow revels in his smart alec superiority, settling bets made in heaven and eventually vowing to spread peace and love across the whole world.

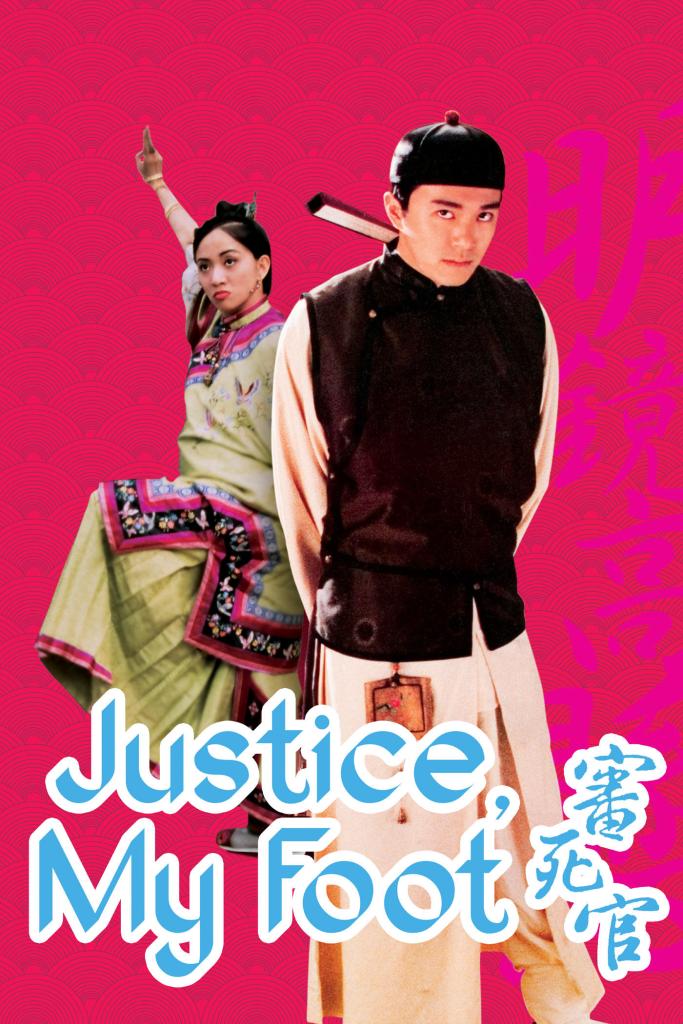

“The Mad Monk” sounds like a great name for a creepy ghost, emerging robed and chanting from the shadows to make you fear for your mortal soul. Sadly, The Mad Monk (濟公, Jì Gōng) features only one “ghost”, but it might just be the cutest in cinema history. The second of Johnnie To’s Shaw Brothers collaborations with comedy star Stephen Chow is another wisecracking romp in which Chow revels in his smart alec superiority, settling bets made in heaven and eventually vowing to spread peace and love across the whole world. Stephen Chow has always been a force of nature but even before making his name as a director in the mid-90s, he contributed his madcap energy to some of the highest grossing movies of the era. Justice, My Foot! (審死官) is very much of the “makes no sense” comedy genre and, directed by Johnnie To for Shaw Brothers, makes great use of the collective propensity for whimsy on offer. Even if not quite managing to keep the momentum going until the closing scenes, Justice, My Foot! succeeds in delivering quick fire (often untranslatable) jokes and period martial arts action sure to keep genre fans happy.

Stephen Chow has always been a force of nature but even before making his name as a director in the mid-90s, he contributed his madcap energy to some of the highest grossing movies of the era. Justice, My Foot! (審死官) is very much of the “makes no sense” comedy genre and, directed by Johnnie To for Shaw Brothers, makes great use of the collective propensity for whimsy on offer. Even if not quite managing to keep the momentum going until the closing scenes, Justice, My Foot! succeeds in delivering quick fire (often untranslatable) jokes and period martial arts action sure to keep genre fans happy.