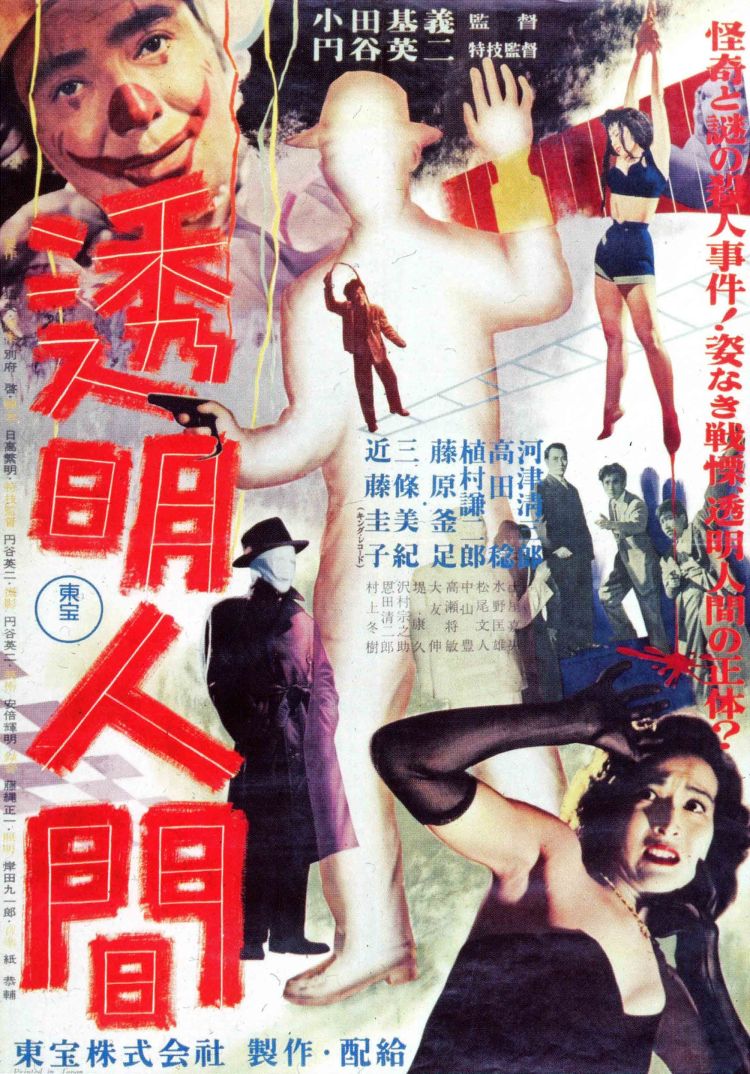

The Invisible Man is a frightening presence precisely because he isn’t there. The living manifestation of the fear of the unknown, he stalks and spies, lurking in our imaginations instilling terror of evil deeds we are powerless to stop. Daiei made Japan’s first Invisible Man movie back in 1949 – a fun crime romp with the underlying message that scientific research is important but not as important as ensuring knowledge is placed in the right hands. Toho brought Eiji Tsuburaya back for another go at the same material in 1954 as part of their burgeoning tokusaku industry fathered by Godzilla. The 1954 Invisible Man (透明人間, Toumei Ningen), directed by Motoyoshi Oda, is once again a criticism of Japan’s wartime past but also perhaps of its future. This Invisible Man is an invisible hero but one whose heroism is only recognised once the mask is removed.

The Invisible Man is a frightening presence precisely because he isn’t there. The living manifestation of the fear of the unknown, he stalks and spies, lurking in our imaginations instilling terror of evil deeds we are powerless to stop. Daiei made Japan’s first Invisible Man movie back in 1949 – a fun crime romp with the underlying message that scientific research is important but not as important as ensuring knowledge is placed in the right hands. Toho brought Eiji Tsuburaya back for another go at the same material in 1954 as part of their burgeoning tokusaku industry fathered by Godzilla. The 1954 Invisible Man (透明人間, Toumei Ningen), directed by Motoyoshi Oda, is once again a criticism of Japan’s wartime past but also perhaps of its future. This Invisible Man is an invisible hero but one whose heroism is only recognised once the mask is removed.

Opening in grand style, the film gets off to a mysterious start when a speeding car hits “something” in the road. The “something” turns out to be a previously invisible man whose appearance is returned to him as blood leaks out from under the now stopped car. In his pocket, the man has a suicide note explaining that living life invisible is just too depressing and he can’t go on. Seeing as the note is addressed to a “friend” who is also apparently an Invisible Man that means there are more out there. Despite there being no real threat involved in any of this, the newscasters are alarmed and the public frightened.

This is quite useful for some – a shady gang quickly starts putting on Invisible Man suits including wrapping their heads in bandages just like in the movies, and robbing banks. Admittedly this makes no practical sense but adds to the ongoing fear of an “invisible” threat. An intrepid reporter, Komatsu (Yoshio Tsuchiya), links the crimes to a nightclub where the head of the gang is also trying to pressure the headline star, Michiyo (Miki Sanjo), into a career as a drug mule. Besides violence, their leverage is the little girl who lives across from Michiyo and is blind – the money they would be paying her could also be used to pay for the girl’s eye surgery. Mariko is waiting patiently for her grandfather to make the money, unaware that he has also fallen under the spell of the criminal gang.

The real “Invisible Man” is doing a good job of hiding in plain sight by proudly standing out in a traditional clown outfit complete with makeup and a fluffy nose. Nanjo (Seizaburo Kawazu) works as a promoter for the club and is also good friends with little Mariko who is unable to see him either with or without his clown suit. Unlike other Invisible Men, Nanjo is good and kind – the curse of his condition has not ruined soul.

He is, however, afraid of being exposed. Aside from social ostracism (perhaps someone who wears a clown suit 24/7 isn’t particularly bothered about that), Nanjo fears what his government would do to him if they discovered he was still alive. Like his friend who later committed suicide, Nanjo was a member of an experimental army squad recruited towards the end of the war as Japan sought to create the ultimate warriors to turn the tide in the battle against the Americans. The Invisible Men were born but the war lost, and it was assumed that they had all fallen. Nanjo, surviving, has been abandoned by the land that he fought for. His existence is a secret, an embarrassing relic of Japan’s attempt at scientific warfare, and something which no one wants to deal with. Nando’s friend could no longer cope with his non-existence. Unable to return home, unable to work, unable to marry, there was no “visible” future which presented itself to him.

In this sense, Nanjo represents a point of view many might have identified with in 1954. These men fought and risked their lives for a god they now say is only a man, to come home to a land ruled by the “enemy” in which they can neither criticise the occupation or the former authorities. These men may well feel “invisible” in the new post-war order in which the younger generation are beginning to break free while they suffer the continuing effects of their wartime service even if not quite as literally as Nanjo.

Yet there’s a kind of internalised resentment within Nanjo who describes himself as a “monster created by militarism”. Disguising himself as a clown he attempts to live a “normal” life though one segregated from mainstream society. A half-hearted romance with club girl Michiyo and a well meaning paternalism for the orphaned little blind girl point to Nanjo’s altruistic heroism but also to a reluctance to fully engage with either of them due to a lingering sense of guilt and shame.

The Invisible Man is the hero here while the bad guys subvert and misuse his name to do their evil deeds, terrorising women and threatening to burn the city down rather than surrender to authority. Even more than others in Toho’s expanding universe of tokusatsu heroes, Invisible Man is a defence of the other as not only valid but morally good even in the face of extreme prejudice and violence. It is, however, also one of their less well considered efforts and Tsuburaya’s effects remain few and far between, rarely moving beyond his work on Daiei’s Invisible Man five years previously. Bulked out with musical numbers and dance sequences, Toho’s Invisible Man is a less satisfying affair than Daei’s puply sci-fi adventure but is nevertheless interesting in its defence of the sad clown who all alone has decided to shoulder the burdens of his world.

Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible.

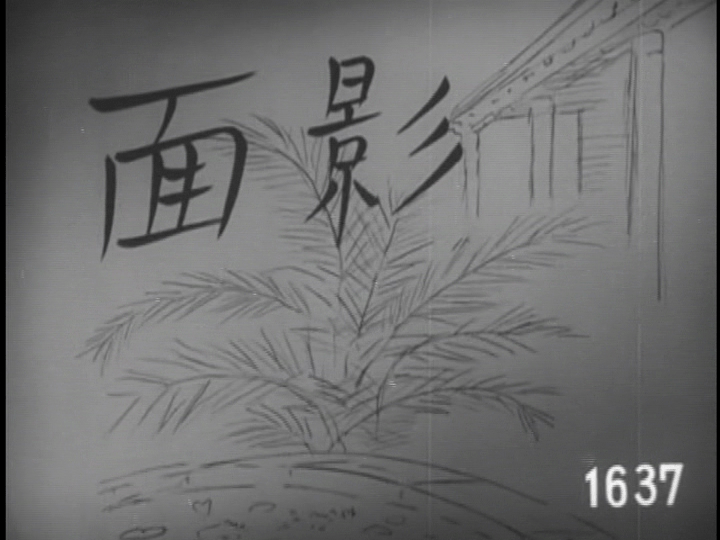

Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible. Master of the shomingeki, Heinosuke Gosho goes upscale for the post-war romantic melodrama, Vestige (面影, omokage), even if he goes out of his way to add a layer of expressionistic imagery. Inspired by Gosho’s own experiences, Vestige has an air of melancholy and of frustrated dreams but also of resignation as the two not quite lovers at the centre agree to quell their romantic yearnings and preserve their conventional, bourgeois lives at the expense of greater happiness.

Master of the shomingeki, Heinosuke Gosho goes upscale for the post-war romantic melodrama, Vestige (面影, omokage), even if he goes out of his way to add a layer of expressionistic imagery. Inspired by Gosho’s own experiences, Vestige has an air of melancholy and of frustrated dreams but also of resignation as the two not quite lovers at the centre agree to quell their romantic yearnings and preserve their conventional, bourgeois lives at the expense of greater happiness. After leaving Shochiku and forming an independent production company with his actress wife Mariko Okada, Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida continued in the Shochiku vein, after a fashion, through crafting what came to be known as “anti-melodramas”. Taking the familiar melodrama a studio like Shochiku was well known for, Yoshida transformed the material through radical cinematography designed to alienate and drain the overwrought drama of its empty emotion in order to drive to something deeper. The Affair (情炎, Jouen), released in 1967, is just such an experiment as it paints the cold and repressed world of its heroine in steely black and white, imprisoning her within its widescreen frame, and setting her at odds with the younger, more liberated generation who get their kicks through groovy beatnik jazz and an eternal party.

After leaving Shochiku and forming an independent production company with his actress wife Mariko Okada, Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida continued in the Shochiku vein, after a fashion, through crafting what came to be known as “anti-melodramas”. Taking the familiar melodrama a studio like Shochiku was well known for, Yoshida transformed the material through radical cinematography designed to alienate and drain the overwrought drama of its empty emotion in order to drive to something deeper. The Affair (情炎, Jouen), released in 1967, is just such an experiment as it paints the cold and repressed world of its heroine in steely black and white, imprisoning her within its widescreen frame, and setting her at odds with the younger, more liberated generation who get their kicks through groovy beatnik jazz and an eternal party.

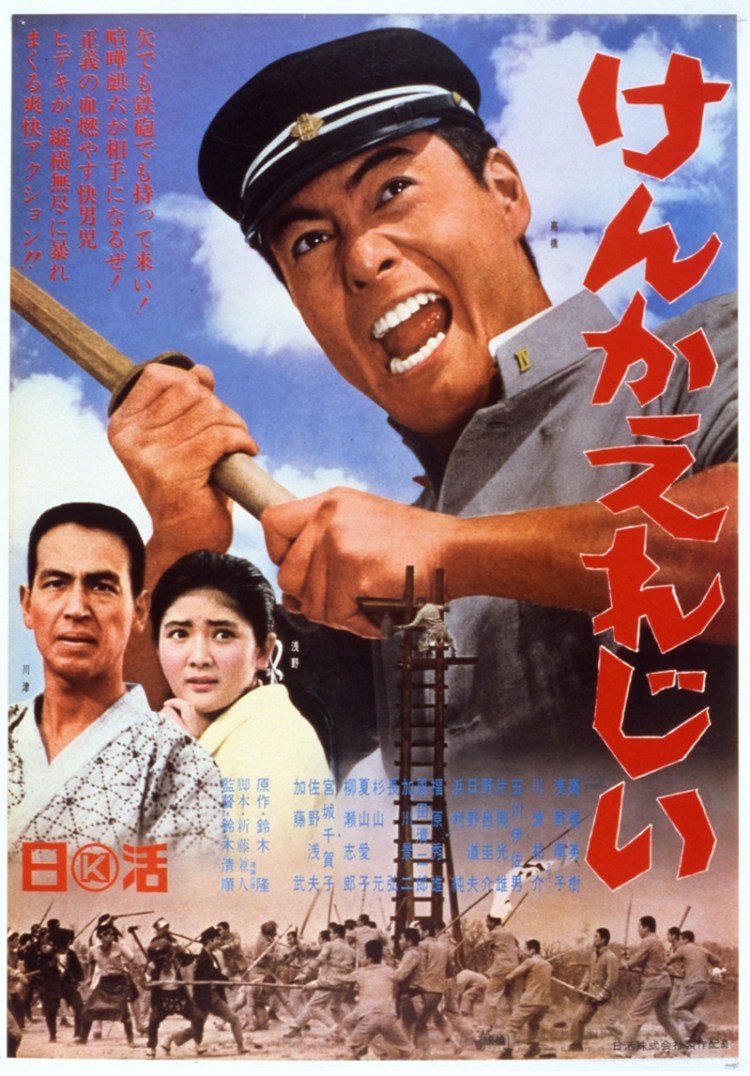

Ah, youth. It explains so many things though, sadly, only long after it’s passed. For the young men who had the misfortune to come of age in the 1930s, their glory days are filled with bittersweet memories as their personal development occurred against a backdrop of increasing political division. Seijun Suzuki was not exactly apolitical in his filmmaking despite his reputation for “nonsense”, but in Fighting Elegy (けんかえれじい, Kenka Elegy) he turns a wry eye back to his contemporaries for a rueful exploration of militarism’s appeal to the angry young man. When emotion must be sublimated and desire repressed, all that youthful energy has to go somewhere and so the unresolved tensions of the young men of Japan brought about an unwelcome revolution in a misguided attempt at mastery over the self.

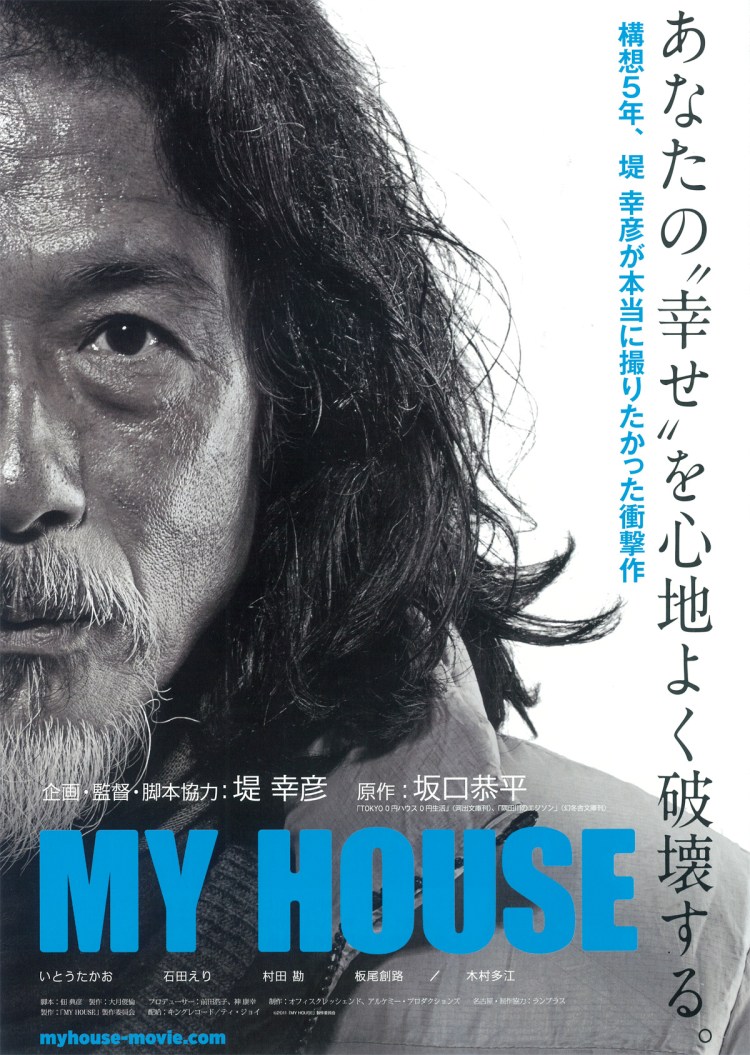

Ah, youth. It explains so many things though, sadly, only long after it’s passed. For the young men who had the misfortune to come of age in the 1930s, their glory days are filled with bittersweet memories as their personal development occurred against a backdrop of increasing political division. Seijun Suzuki was not exactly apolitical in his filmmaking despite his reputation for “nonsense”, but in Fighting Elegy (けんかえれじい, Kenka Elegy) he turns a wry eye back to his contemporaries for a rueful exploration of militarism’s appeal to the angry young man. When emotion must be sublimated and desire repressed, all that youthful energy has to go somewhere and so the unresolved tensions of the young men of Japan brought about an unwelcome revolution in a misguided attempt at mastery over the self. Yukihiko Tsutsumi has made some of the most popular films at the Japanese box office yet his name might not be one that’s instantly familiar to filmgoers. Tsutsumi has become a top level creator of mainstream blockbusters, often inspired by established franchises such as TV drama or manga. Skilled in many genres from the epic sci-fi of Twentieth Century Boys to the mysterious comedy of Trick and the action of SPEC, Tsutsumi’s consumate abilities have taken on an anonymous quality as the franchise takes centre stage which makes this indie leaning black and white exploration of the lives of a group of homeless people in Nagoya all the more surprising.

Yukihiko Tsutsumi has made some of the most popular films at the Japanese box office yet his name might not be one that’s instantly familiar to filmgoers. Tsutsumi has become a top level creator of mainstream blockbusters, often inspired by established franchises such as TV drama or manga. Skilled in many genres from the epic sci-fi of Twentieth Century Boys to the mysterious comedy of Trick and the action of SPEC, Tsutsumi’s consumate abilities have taken on an anonymous quality as the franchise takes centre stage which makes this indie leaning black and white exploration of the lives of a group of homeless people in Nagoya all the more surprising. Although Masahiro Shinoda has long been admitted into the pantheon of Japanese New Wave masters, he is mostly remembered only for his 1969 adaptation of a Chikamatsu play, Double Suicide. Less overtly political than many of his contemporaries during the heady years of protest and rebellion, Shinoda was a consummate stylist whose films aimed to dazzle with visual flair or often to deliberately disorientate with their worlds of constant uncertainty. Like so many of the directors who would go on to form what would retrospectively become known as the Japanese New Wave, Shinoda also started out as a junior AD, in this case at Shochiku where he felt himself stifled by the studio’s famously safe, inoffensive approach to filmmaking.

Although Masahiro Shinoda has long been admitted into the pantheon of Japanese New Wave masters, he is mostly remembered only for his 1969 adaptation of a Chikamatsu play, Double Suicide. Less overtly political than many of his contemporaries during the heady years of protest and rebellion, Shinoda was a consummate stylist whose films aimed to dazzle with visual flair or often to deliberately disorientate with their worlds of constant uncertainty. Like so many of the directors who would go on to form what would retrospectively become known as the Japanese New Wave, Shinoda also started out as a junior AD, in this case at Shochiku where he felt himself stifled by the studio’s famously safe, inoffensive approach to filmmaking. Review of Zhang Lu’s A Quiet Dream (춘몽, Chun-mong) first published by

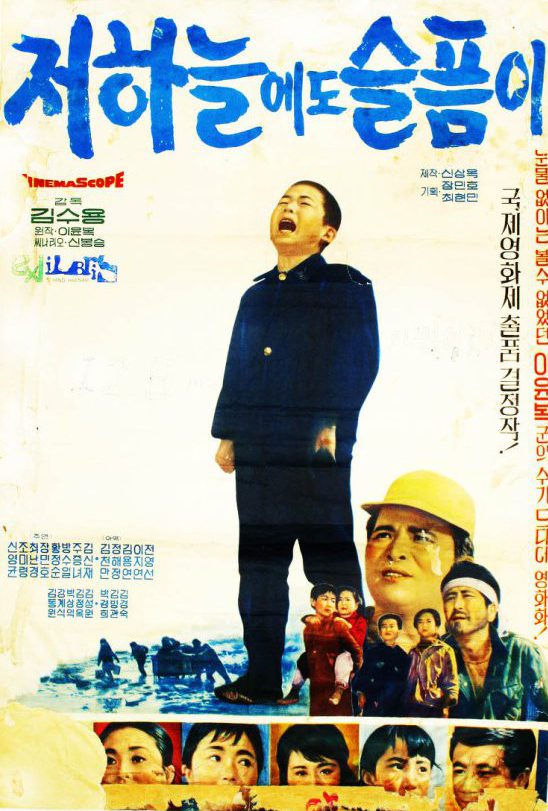

Review of Zhang Lu’s A Quiet Dream (춘몽, Chun-mong) first published by  It’s a sorry enough tale to hear that many silent classics no longer exist, regarded only as disposable entertainment and only latterly collected into archives and preserved as valuable film history, but in the case of South Korea even mid and late 20th century films are unavailable thanks to the country’s turbulent political history. Though often listed among the greats of 1960s Korean cinema, Sorrow Even Up in Heaven (저 하늘에도 슬픔이, Jeo Haneuledo Seulpeumi) was presumed lost until a Mandarin subtitled print was discovered in an archive in Taiwan. Now given a full restoration by the Korean Film Archive, Kim’s tale of societal indifference to childhood poverty has finally been returned to its rightful place in cinema history but, as Kim’s own attempt to remake the film 20 years later bears out, how much has really changed?

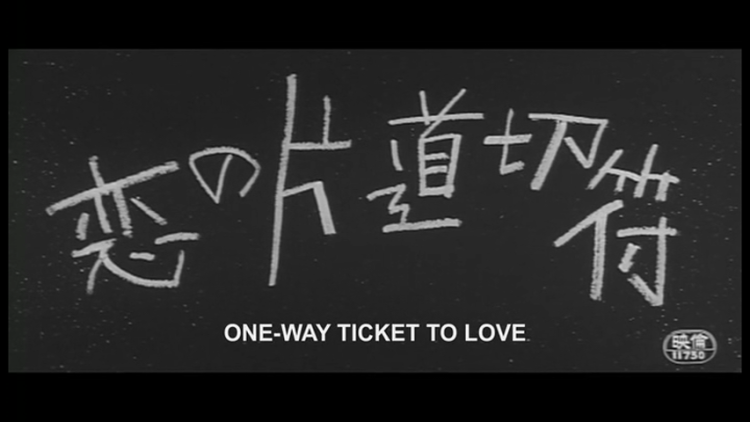

It’s a sorry enough tale to hear that many silent classics no longer exist, regarded only as disposable entertainment and only latterly collected into archives and preserved as valuable film history, but in the case of South Korea even mid and late 20th century films are unavailable thanks to the country’s turbulent political history. Though often listed among the greats of 1960s Korean cinema, Sorrow Even Up in Heaven (저 하늘에도 슬픔이, Jeo Haneuledo Seulpeumi) was presumed lost until a Mandarin subtitled print was discovered in an archive in Taiwan. Now given a full restoration by the Korean Film Archive, Kim’s tale of societal indifference to childhood poverty has finally been returned to its rightful place in cinema history but, as Kim’s own attempt to remake the film 20 years later bears out, how much has really changed? Aside from the genre defining Crazed Fruit which kick-started the era of the “seishun eiga” and, in its own way, the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira has remained under seen and under appreciated outside of Japan. Completed just three years after the youth fuelled frenzy of Crazed Fruit with its freewheeling playboys and their speedboat crises, The Assignation (密会, Mikkai) is a much more measured, mature meditation on social constraint, guilt and the slow drip feed of poisonous thought. Nakahira wastes none of his characteristic energy in the necessarily tight 76 minute runtime, but this is an exercise in high tension as a pair of illicit lovers are suddenly confronted with their crime after accidentally witnessing a murder.

Aside from the genre defining Crazed Fruit which kick-started the era of the “seishun eiga” and, in its own way, the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira has remained under seen and under appreciated outside of Japan. Completed just three years after the youth fuelled frenzy of Crazed Fruit with its freewheeling playboys and their speedboat crises, The Assignation (密会, Mikkai) is a much more measured, mature meditation on social constraint, guilt and the slow drip feed of poisonous thought. Nakahira wastes none of his characteristic energy in the necessarily tight 76 minute runtime, but this is an exercise in high tension as a pair of illicit lovers are suddenly confronted with their crime after accidentally witnessing a murder.