The well known Natsume Soseki novel, Botchan, tells the story of an arrogant, middle class Tokyoite who reluctantly accepts a teaching job at a rural school where he relentlessly mocks the locals’ funny accent and looks down on his oikish pupils all the while dreaming of his loyal family nanny. Hiroshi Shimizu’s Nobuko (信子) is almost an inverted picture of Soseki’s work as its titular heroine travels from the country to a posh girls’ boarding school bringing her country bumpkin accent and no nonsense attitude with her. Like Botchan, though for very different reasons, Nobuko also finds herself at odds with the school system but remains idealistic enough to recommend a positive change in the educational environment.

The well known Natsume Soseki novel, Botchan, tells the story of an arrogant, middle class Tokyoite who reluctantly accepts a teaching job at a rural school where he relentlessly mocks the locals’ funny accent and looks down on his oikish pupils all the while dreaming of his loyal family nanny. Hiroshi Shimizu’s Nobuko (信子) is almost an inverted picture of Soseki’s work as its titular heroine travels from the country to a posh girls’ boarding school bringing her country bumpkin accent and no nonsense attitude with her. Like Botchan, though for very different reasons, Nobuko also finds herself at odds with the school system but remains idealistic enough to recommend a positive change in the educational environment.

Travelling from the country to take up her teaching job, Nobuko (Mieko Takamine) moves in with her geisha aunt to save money. When she gets to the school she finds out that she’s been shifted from Japanese to P.E. (not ideal, but OK) and there are also a few deductions from her pay which no one had mentioned. The stern but kindly headmistress is quick to point out Nobuko’s strong country accent which is not compatible with the elegant schooling on offer. The most important thing she says is integrity. Women have to be womanly, poised and “proper”. Nobuko, apparently, has a lot to learn.

As many teachers will attest, the early days are hard and Nobuko finds it difficult to cope with her rowdy pupils who deliberately mock her accent and are intent on winding up their new instructor. One girl in particular, Eiko (Mitsuko Miura), has it in for Nobuko and constantly trolls her with pranks and tricks as well as inciting the other girls to join in with her. As it turns out, Eiko is something of a local trouble maker but no one does anything because her father is a wealthy man who has donated a large amount of money to the school and they don’t want to upset him. This attitude lights a fire in Nobuko, to her the pupils are all the same and should be treated equally no matter who their parents are. As Nobuko’s anger and confidence in her position grow, so does Eiko’s wilfull behaviour, but perhaps there’s more to it than a simple desire to misbehave.

Released in 1940, Nobuko avoids political comment other than perhaps advocating for the importance of discipline and education. It does however subtly echo Shimizu’s constant class concerns as “country bumpkin” Nobuko has to fight for her place in the “elegant” city by dropping her distinctive accent for the standard Tokyo dialect whilst making sure she behaves in an “appropriate” fashion for the teacher of upper class girls.

This mirrors her experience at her aunt’s geisha house which she is eventually forced to move out of when the headmistress finds out what sort of place she’s been living in and insists that she find somewhere more suitable for her position. The geisha world is also particular and regimented, but the paths the two sets of female pupils have open to them are very different. Nobuko quickly makes friends with a clever apprentice geisha, Chako (Sachiko Mitani), who would have liked to carry on at school but was sold owing to her family’s poverty. Though she never wanted to be a geisha, Chako exclaims that if she’s going to have to be one then she’s going to be the world’s best, all the while knowing that her path has been chosen for her and has a very definite end point as exemplified by Nobuko’s aunt – an ageing manageress who’s getting too old to be running the house for herself.

Eiko’s problems are fairly easy to work out, it’s just a shame that no one at the school has stopped to think about her as a person rather than as the daughter of a wealthy man. Treated as a “special case” by the teachers and placed at a distance with her peers, Eiko’s constant acting up is a thinly veiled plea for attention but one which is rarely answered. Only made lonely by a place she hoped would offer her a home, Eiko begins to build a bond with Nobuko even while she’s pushing her simply because she’s the only one to push back. After Nobuko goes too far and Eiko takes a drastic decision, the truth finally comes out, leading to regrets and recriminations all round. Despite agreeing with the headmistress that perhaps she should have turned a blind eye like the other teachers, Nobuko reinforces her philosophy that the girls are all the same and deserve to be treated as such, but also adds that they are each in need of affection and the teachers need to be aware of this often neglected part of their work.

Lessons have been learned and understandings reached, the school environment seems to function more fully with a renewed commitment to caring for each of the pupils as individuals with distinct needs and personalities. Even Chako seems as if she may get a much happier ending thanks to Nobuko’s intervention. An unusual effort for the time in that only two male characters appear (one a burglar Nobuko heroically ejects assuming him to be Eiko playing a prank, and the other Eiko’s father) this entirely female led drama neatly highlights the various problems faced by women of all social classes whilst also emphasising Shimizu’s core humanist philosophies where compassion and understanding are found to be essential components of a fully functioning society.

Isn’t it sad that it’s always the kids that end up hurt when parents fight? Throughout Shimizu’s long career of child centric cinema, the one recurring motif is in the sheer pain of a child who suddenly finds the other kids won’t play with him anymore even though he doesn’t think he’s done anything wrong. Four Seasons of Children (子どもの四季, Kodomo no Shiki) is actually a kind of companion piece to

Isn’t it sad that it’s always the kids that end up hurt when parents fight? Throughout Shimizu’s long career of child centric cinema, the one recurring motif is in the sheer pain of a child who suddenly finds the other kids won’t play with him anymore even though he doesn’t think he’s done anything wrong. Four Seasons of Children (子どもの四季, Kodomo no Shiki) is actually a kind of companion piece to  It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest.

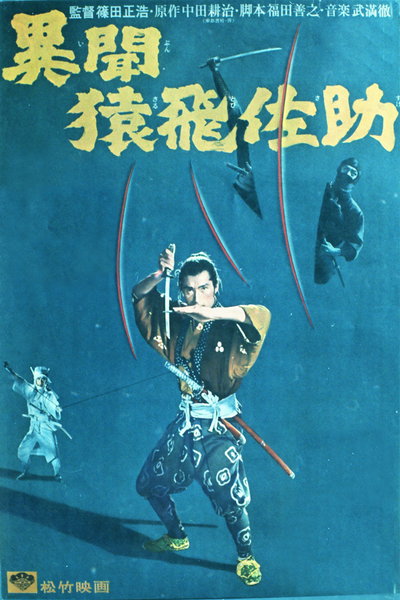

It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest. Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost?

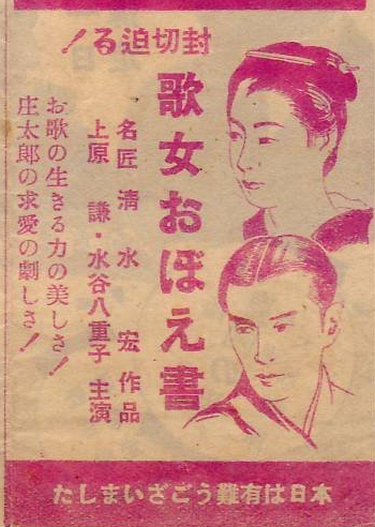

Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost? Filmed in 1941, Notes of an Itinerant Performer (歌女おぼえ書, Utajo Oboegaki ) is among the least politicised of Shimizu’s output though its odd, domestic violence fuelled, finally romantic resolution points to a hardening of his otherwise progressive social ideals. Neatly avoiding contemporary issues by setting his tale in 1901 at the mid-point of the Meiji era as Japanese society was caught in a transitionary phase, Shimizu similarly casts his heroine adrift as she decides to make a break with the hand fate dealt her and try her luck in a more “civilised” world.

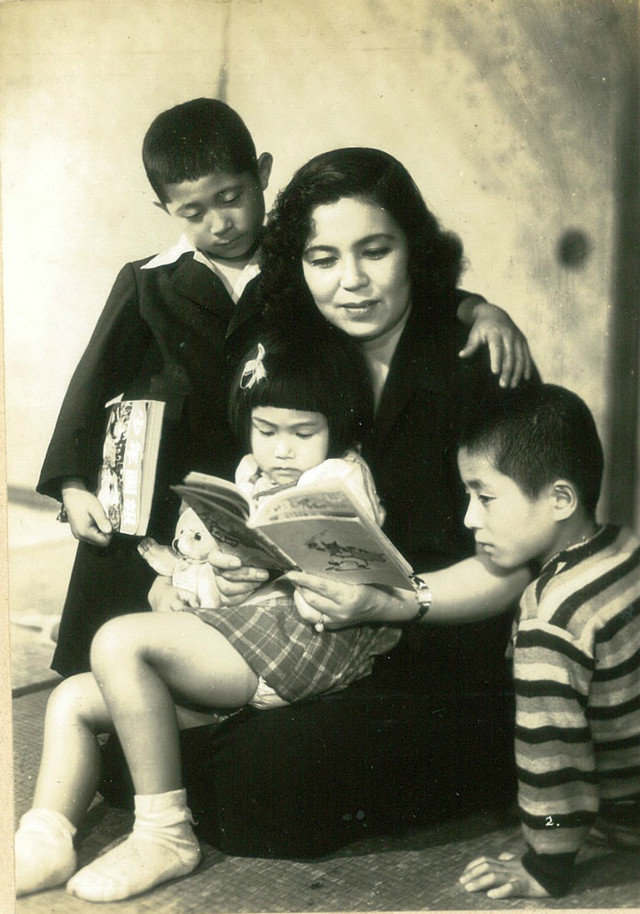

Filmed in 1941, Notes of an Itinerant Performer (歌女おぼえ書, Utajo Oboegaki ) is among the least politicised of Shimizu’s output though its odd, domestic violence fuelled, finally romantic resolution points to a hardening of his otherwise progressive social ideals. Neatly avoiding contemporary issues by setting his tale in 1901 at the mid-point of the Meiji era as Japanese society was caught in a transitionary phase, Shimizu similarly casts his heroine adrift as she decides to make a break with the hand fate dealt her and try her luck in a more “civilised” world. Shimizu’s depression era work was not lacking in down on their luck single mothers forced into difficult positions as they fiercely fought for their children’s future, but 1950’s A Mother’s Love (母情, Bojo) takes an entirely different approach to the problem. Once again Shimizu displays his customary sympathy for all but this particular mother, Toshiko, does not immediately seem to be the self sacrificing embodiment of maternal virtues that the genre usually favours.

Shimizu’s depression era work was not lacking in down on their luck single mothers forced into difficult positions as they fiercely fought for their children’s future, but 1950’s A Mother’s Love (母情, Bojo) takes an entirely different approach to the problem. Once again Shimizu displays his customary sympathy for all but this particular mother, Toshiko, does not immediately seem to be the self sacrificing embodiment of maternal virtues that the genre usually favours. It’s tough being young. The Boss’ Son At College (大学の若旦那, Daigaku no Wakadanna) is the first, and only surviving, film in a series which followed the adventures of the well to do son of a soy sauce manufacturer set in the contemporary era. Somewhat autobiographical, Shimizu’s film centres around the titular boss’ son as he struggles with conflicting influences – those of his father and the traditional past and those of his forward looking, hedonistic youth.

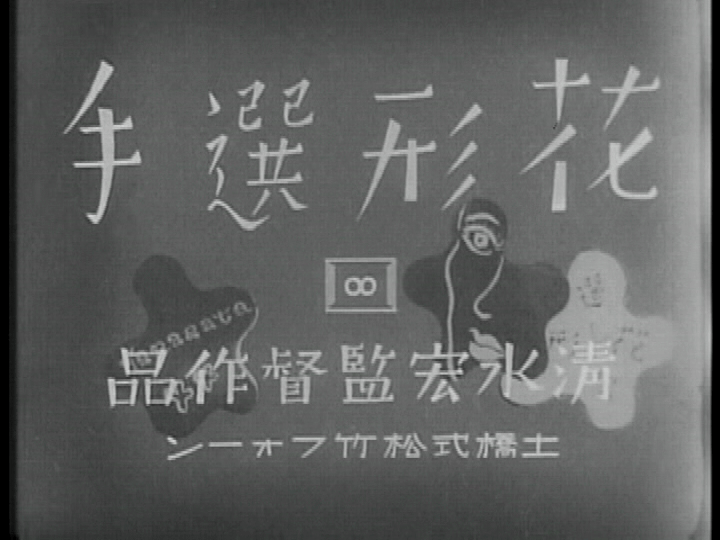

It’s tough being young. The Boss’ Son At College (大学の若旦那, Daigaku no Wakadanna) is the first, and only surviving, film in a series which followed the adventures of the well to do son of a soy sauce manufacturer set in the contemporary era. Somewhat autobiographical, Shimizu’s film centres around the titular boss’ son as he struggles with conflicting influences – those of his father and the traditional past and those of his forward looking, hedonistic youth. Japan in 1937 – film is propaganda, yet Hiroshi Shimizu once again does what he needs to do in managing to pay mere lip service to his studio’s aims. Star Athlete (花形選手, Hanagata senshu) is, ostensibly, a college comedy in which a group of university students debate the merits of physical vs cerebral strength and the place of the individual within the group yet it resolutely refuses to give in to the prevailing narrative of the day that those who cannot or will not conform must be left behind.

Japan in 1937 – film is propaganda, yet Hiroshi Shimizu once again does what he needs to do in managing to pay mere lip service to his studio’s aims. Star Athlete (花形選手, Hanagata senshu) is, ostensibly, a college comedy in which a group of university students debate the merits of physical vs cerebral strength and the place of the individual within the group yet it resolutely refuses to give in to the prevailing narrative of the day that those who cannot or will not conform must be left behind. Sad stories of single mothers forced to work in the world of low entertainment are not exactly rare in pre-war Japanese cinema yet Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1937 entry, Forget Love For Now (Koi mo Wasurete) , puts his on own characteristic spin on things by looking at the situation through the eyes of the young son, Haru (Jun Yokoyama). Frustrated by both social and economic woes, little Haru’s life is blighted by loneliness and resentment culminating in tragedy for all.

Sad stories of single mothers forced to work in the world of low entertainment are not exactly rare in pre-war Japanese cinema yet Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1937 entry, Forget Love For Now (Koi mo Wasurete) , puts his on own characteristic spin on things by looking at the situation through the eyes of the young son, Haru (Jun Yokoyama). Frustrated by both social and economic woes, little Haru’s life is blighted by loneliness and resentment culminating in tragedy for all. Like many other areas of the world in the first half of the 20th century, Japan also found itself at a dividing line of political thought with militarism on the rise from the late 1920s. Despite the onward march of right-wing ideology, the left was not necessarily silent. Ironically, the then voiceless cinema was able to speak for those who were its greatest consumers as an accidental genre was born detailing the everyday hardships faced by those at the bottom end of the ladder. These “proletarian films” or “tendency films” (keiko eiga) were increasingly suppressed as time went on yet, in contrast to the more politically overt cinema of the independent Proletarian Film League of Japan, continued to be produced by mainstream studios. Long thought lost, Shigeyoshi Suzuki’s What Made Her Do It? (何が彼女をそうさせたか, Nani ga Kanojo wo Sousaseta ka) was a major hit on its original release with some press reports even claiming the film provoked riots when audiences were passionately moved by the heroine’s tragic descent into madness and arson after suffering countless cruelties in an unfeeling world.

Like many other areas of the world in the first half of the 20th century, Japan also found itself at a dividing line of political thought with militarism on the rise from the late 1920s. Despite the onward march of right-wing ideology, the left was not necessarily silent. Ironically, the then voiceless cinema was able to speak for those who were its greatest consumers as an accidental genre was born detailing the everyday hardships faced by those at the bottom end of the ladder. These “proletarian films” or “tendency films” (keiko eiga) were increasingly suppressed as time went on yet, in contrast to the more politically overt cinema of the independent Proletarian Film League of Japan, continued to be produced by mainstream studios. Long thought lost, Shigeyoshi Suzuki’s What Made Her Do It? (何が彼女をそうさせたか, Nani ga Kanojo wo Sousaseta ka) was a major hit on its original release with some press reports even claiming the film provoked riots when audiences were passionately moved by the heroine’s tragic descent into madness and arson after suffering countless cruelties in an unfeeling world.