Koichi Goto’s Art Theatre Guild adaptation of Kenji Maruyama’s 1968 novel At Noon (正午なり, Mahiru Nari) begins with a young man on a train. Forlornly looking out of the window, he remains aboard until reaching his rural hometown where he makes a late entry to his parents’ house and is greeted a little less than warmly by his mother. The boy, Tadao, refuses to say why he’s left the big city so abruptly to return to the beautiful, if dull, rural backwater where he grew up.

Koichi Goto’s Art Theatre Guild adaptation of Kenji Maruyama’s 1968 novel At Noon (正午なり, Mahiru Nari) begins with a young man on a train. Forlornly looking out of the window, he remains aboard until reaching his rural hometown where he makes a late entry to his parents’ house and is greeted a little less than warmly by his mother. The boy, Tadao, refuses to say why he’s left the big city so abruptly to return to the beautiful, if dull, rural backwater where he grew up.

There’s little work here for a young man, which is why Tadao left in the first place. After using some family connections to try and find a job, he finally decides to make use of his abilities by fixing radios and TV sets for a local electronics store. To begin with he doesn’t want to see his old friend, Tetsuji, perhaps out of a sense of shame at having returned home but the pair later strike up their old friendship – that is, until Tetsuji suddenly announces his plans to run away with a local bar hostess.

It’s never quite revealed what happened to Tadao in Tokyo but it seems to have been something serious enough to change the course of his entire life and send him reeling back home depressed and angry. In many ways he’s a typical young man, if slightly sullen, but he’s developed a serious number of sexual hangups which have turned him into some kind of repressed, misogynistic, pervert. He appears to have made a deliberate decision to dislike the idea of women, or at least the idea of women with sexual appeal. He thinks women are trouble, that no good comes of love, but can’t stop himself from spying on the female tourists staying in an upper room. He’s always looking, staring invasively, but resolved not to touch.

Tadao has already been to the city and evidently found it not quite to his liking but his friend, Tetsuji, feels bored in the village and trapped by his parents who need his help in their orchards. When Tadao realises Tetsuji is taking the hostess with him when he skips town, he asks for the money he just agreed to lend him back and tells him to forget about running away and just to go home. Unfortunately for Tetsuji, Tadao’s advice proves sound as his city dreams don’t work out the way he planned either. To end his frequent attempts to escape, Tetsuji’s family float the idea of an arranged marriage which originally horrifies both boys but after meeting his prospective bride, Tetsuji changes his mind. Tadao doesn’t approve, but after meeting the girl in question and seeing that she is quite lovely changes his mind too and is happy for his friend – that is, until he realises Tetsuji has only introduced him to her as a pretext of getting her on her own to enact his marital rights a little ahead of schedule. This breach of morality proves the final straw for Tadao who does not like the idea of his wayward friend deceiving and then ruining this innocent young flower who’s far too good for him anyway.

Tadao’s fascination with another damaged bar girl, Akemi, continues as the two find themselves both looking at the sad figure of a tethered eagle imprisoned at the local zoo. Akemi says she likes to look at the bird as she feels perhaps somehow that helps him escape. She feels like a caged bird too – trapped in a bad relationship with a useless boyfriend who has a vague plan of turning manure into an energy source while she supports them both by working at a hostess bar and hating every second of it. Tadao feels trapped in a hundred different ways, by his town, by his parents, by whatever happened in Tokyo, and by his own pent-up frustrations. By this point, he’s a one man powder keg ready to explode and after blowing his final safety caps, tragedy is the only possible outcome.

At Noon begins with its epilogue, but uncomfortably frames its protagonist’s despicable final actions with an odd kind of heroism as his head eclipses the sun leaving him with a radiant halo. He may have satisfied himself in some way, put to rest some of that inner turmoil, but what he’s done is something truly dreadful and driven by an intensely animalistic instinct. At Noon may have something to say about the dangers of frustrated young men with no work to go to, no ambition to follow, and no luck with the ladies but displays an oddly ambivalent attitude to its deranged protagonist that makes for often uncomfortable viewing.

By the way, After Noon has music by Ray Davis of The Kinks!

Unsubbed Trailer:

If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to live in hell, you could enjoy this fascinating promotional video which recounts events set in an isolated rural monastery somewhere in snow covered Japan. A debut feature from Tatsushi Omori (younger brother of actor Nao Omori who also plays a small part in the film), The Whispering of the Gods (ゲルマニウムの夜, Germanium no Yoru) adapted from the 1998 novel by Mangetsu Hanamura, paints an increasingly bleak picture of human nature as the lines between man and beast become hopelessly blurred in world filled with existential despair.

If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to live in hell, you could enjoy this fascinating promotional video which recounts events set in an isolated rural monastery somewhere in snow covered Japan. A debut feature from Tatsushi Omori (younger brother of actor Nao Omori who also plays a small part in the film), The Whispering of the Gods (ゲルマニウムの夜, Germanium no Yoru) adapted from the 1998 novel by Mangetsu Hanamura, paints an increasingly bleak picture of human nature as the lines between man and beast become hopelessly blurred in world filled with existential despair. Nobuhiko Obayashi might be most closely associated with his debut, Hausu, which takes the form of a surreal, totally psychedelic haunted house movie, but in many ways his first feature is not particularly indicative of the rest of Obayashi’s output. 1984’s The Deserted City (AKA Haishi, 廃市), is a much better reflection of the director’s most prominent preoccupations as it once again sees the protagonist taking a journey of memory back to a distant youth which is both forgotten in name yet ever present like an anonymous ghost haunting the narrator with long held regrets and recriminations.

Nobuhiko Obayashi might be most closely associated with his debut, Hausu, which takes the form of a surreal, totally psychedelic haunted house movie, but in many ways his first feature is not particularly indicative of the rest of Obayashi’s output. 1984’s The Deserted City (AKA Haishi, 廃市), is a much better reflection of the director’s most prominent preoccupations as it once again sees the protagonist taking a journey of memory back to a distant youth which is both forgotten in name yet ever present like an anonymous ghost haunting the narrator with long held regrets and recriminations. The stories of samurai whose soul is placed not in the sword but in another tool are quickly becoming a genre all of their own. Coming from the same screen writer as

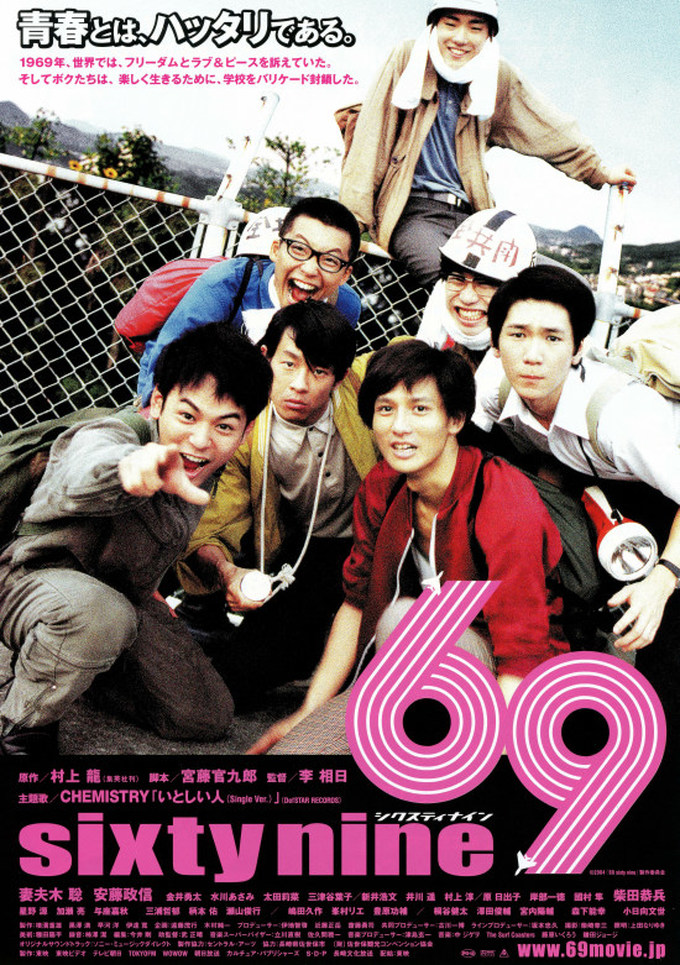

The stories of samurai whose soul is placed not in the sword but in another tool are quickly becoming a genre all of their own. Coming from the same screen writer as  Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story

Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story  Times change, and men must change with them or they must die. When Japan was forced to open up to the rest of the world after centuries of isolation, its ancient order of samurai with their feudal lords and subjugated peasantry was abandoned in favour of a more Western looking democratic solution to social stratification. Suddenly the entirety of a man’s life was rendered nil – no more lords to serve, a man must his make his own way now. However, for some, old wounds continue to fester, making it impossible for them to embrace this entirely new way of thinking.

Times change, and men must change with them or they must die. When Japan was forced to open up to the rest of the world after centuries of isolation, its ancient order of samurai with their feudal lords and subjugated peasantry was abandoned in favour of a more Western looking democratic solution to social stratification. Suddenly the entirety of a man’s life was rendered nil – no more lords to serve, a man must his make his own way now. However, for some, old wounds continue to fester, making it impossible for them to embrace this entirely new way of thinking. One of the most surprising things about the 1978 novel When I Sense the Sea is that its author was only 18 years old when the book was published. Though the protagonist begins as a 16 year old high school girl, author Kei Nakazawa follows her on into adulthood as the damage done to her teenage psyche radiates like a series of tiny, branching chasms stretching far back into a difficult childhood. This 2015 adaptation from Hiroshi Ando, Undulant Fever (海を感じる時, Umi wo Kanjiru Toki), maintains a distant and detached tone which, while not shying away from the erotic nature of the discussion, is quick to underline the unfulfilling and often utilitarian nature of the central couple’s relationship.

One of the most surprising things about the 1978 novel When I Sense the Sea is that its author was only 18 years old when the book was published. Though the protagonist begins as a 16 year old high school girl, author Kei Nakazawa follows her on into adulthood as the damage done to her teenage psyche radiates like a series of tiny, branching chasms stretching far back into a difficult childhood. This 2015 adaptation from Hiroshi Ando, Undulant Fever (海を感じる時, Umi wo Kanjiru Toki), maintains a distant and detached tone which, while not shying away from the erotic nature of the discussion, is quick to underline the unfulfilling and often utilitarian nature of the central couple’s relationship. Yusaku Matsuda became a household name and all round cool guy hero thanks to his role as a maverick private eye in the hit TV show Detective Story, however despite sharing the same name, Kichitaro Negishi’s Detective Story movie from 1983 (探偵物語, Tantei Monogatari) has absolutely nothing to with the identically titled drama series. In fact, Matsuda is not even the star attraction here as the film is clearly built around top idol of the day Hiroko Yakushimaru as it adapts a novel which is also published by the agency that represents her and even works some of her music into the soundtrack.

Yusaku Matsuda became a household name and all round cool guy hero thanks to his role as a maverick private eye in the hit TV show Detective Story, however despite sharing the same name, Kichitaro Negishi’s Detective Story movie from 1983 (探偵物語, Tantei Monogatari) has absolutely nothing to with the identically titled drama series. In fact, Matsuda is not even the star attraction here as the film is clearly built around top idol of the day Hiroko Yakushimaru as it adapts a novel which is also published by the agency that represents her and even works some of her music into the soundtrack. Back in 2008 as the financial crisis took hold, a left leaning early Showa novel from Takiji Kobayashi, Kanikosen (蟹工船), became a surprise best seller following an advertising campaign which linked the struggles of its historical proletarian workers with the put upon working classes of the day. The book had previously been adapted for the screen in 1953 in a version directed by So Yamamura but bolstered by its unexpected resurgence, another adaptation directed by SABU arrived in 2009.

Back in 2008 as the financial crisis took hold, a left leaning early Showa novel from Takiji Kobayashi, Kanikosen (蟹工船), became a surprise best seller following an advertising campaign which linked the struggles of its historical proletarian workers with the put upon working classes of the day. The book had previously been adapted for the screen in 1953 in a version directed by So Yamamura but bolstered by its unexpected resurgence, another adaptation directed by SABU arrived in 2009. A late career entry from socially minded director Shohei Imamura, Dr. Akagi (カンゾー先生, Kanzo Sensei) takes him back to the war years but perhaps to a slightly more bourgeois milieu than his previous work had hitherto focussed on. Based on the book by Ango Sakaguchi, Dr. Akagi is the story of one ordinary “family doctor” in the dying days of World War II.

A late career entry from socially minded director Shohei Imamura, Dr. Akagi (カンゾー先生, Kanzo Sensei) takes him back to the war years but perhaps to a slightly more bourgeois milieu than his previous work had hitherto focussed on. Based on the book by Ango Sakaguchi, Dr. Akagi is the story of one ordinary “family doctor” in the dying days of World War II.