It’s all go in Kabukicho in Eiji Uchida and Shinzo Katayama’s zany tale of aliens, serial killers, and secret assassins. The film’s Japanese title (探偵マリコの生涯で一番悲惨な日, Tantei Mariko no Shogai de ichiban Hisanna Hi), the most tragic day in the life of detective Mariko, may hint at the melancholy at the centre of the story in putting the titular investigator front and centre even while her success is fuelled by her position on the periphery but this is also very much the story of an area and community in a shrinking part of the city.

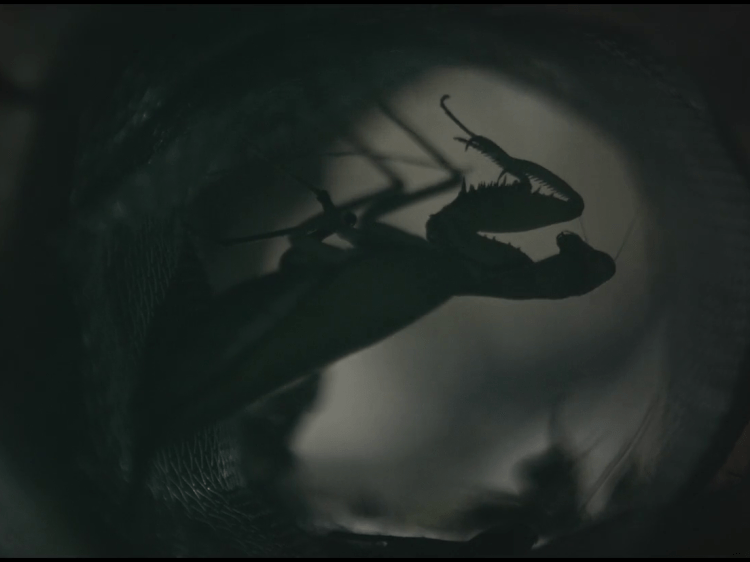

It’s true enough that Mariko’s (Sairi Ito) karaoke bar seems to have become a local community hub filled with a series of regulars each of whom have stories of their own. Born and raised in Kabukicho, Mariko knows every inch of the area and thanks to the confessional quality of her work has her finger truly on the pulse which is what makes her such a good detective. Her case this time around is though a little more difficult as she’s been hired by the FBI to track down an escaped space alien because all aliens apparently belong to the US. This one’s been liberated by a mad scientist, Amamoto (Shohei Uno), who they say wants to team up with the alien for ill intent.

In what seems to be a nod to cult 1983 horror movie Basket Case, Amamoto carries the alien around in a picnic basket from which it occasionally irradiates people when frightened. Meanwhile, a serial killer is also stalking the area. One of Mariko’s regulars, Ayaka (Shiori Kubo), is keen to catch him though not for justice but the reward because she’s become obsessed with a bar host who’s been spending a lot of time with another customer because she can pay more. Mariko turns her offer down on the grounds that she doesn’t want to enable her romantic folly and otherwise seems rather uninterested in the serial killer case perhaps because no one’s hired her to solve it, but she also refuses a job from another regular who wants to track down his estranged daughter after being forced on a suicide mission by his former yakuza associates possibly because she suspects he won’t like the answer when she finds her.

Home to the red light district, Kabukicho has a rather seedy reputation but here has a kind of homeliness in which the veneer of sleaze is of course perfectly normal and unremarkable. A yakuza intimidates a love hotel worker while standing directly in front of a rotating electric dildo in an S&M-themed room later visited by one of Mariko’s regulars with her nerdy film director crush who is so sensitive he can barely walk after exiting the cinema so moved is he by the cinematic expression. Most of the regulars are in their own way lovelorn and lonely, perhaps no less Mariko herself who has an attachment to a middle-aged ex-chef (Yutaka Takenouchi) who now runs a moribund dojo teaching ninja skills to anyone willing to learn. Despite the warmth of the community, life in Kabukicho can be hard as the host later echoes looking around his tiny apartment and sighing that he’s tired. It took so much out of him just to get this little and he barely has it in him anymore.

Mariko too has her sorrow and buried trauma, hiding out in her bar but secretly imprisoned within the borders of Kabukicho as a kind of self-imposed punishment linked to her tragic past. The intersecting stories paint a vivid picture of an absurd world in which the innocuous civil servant next to you might be a secret assassin or you could turn a corner and run into a serial killer, not to mention a mad scientist with an alien in a basket. But for all its craziness it has a kind of integrity in which the strange is also perfectly normal and Mariko becomes a kind of anchor restoring order to an unruly world. As she’s fond of saying thing’s will work out and it’s difficult not to believe her or the defiantly upbeat spirit even among those depressed and downtrodden otherwise unable to escape the confines of a purgatorial Kabukicho.

Life of Mariko in Kabukicho screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Original trailer (English subtitles)