An apathetic college student is pulled between nihilistic destruction and the desire for life in Ken Ninomiya’s adaptation of the novel by F, Midnight Maiden War (真夜中乙女戦争, Mayonaka Otome Senso). “Do those who struggle for life deserve to be defeated as evil?” is a question that is put to him while he asks himself if there’s something wrong in his yearning for a “boring”, conventional existence with a good job, house in the suburbs and people to share it. Then again as the forces of darkness point out, those who long for normality usually cannot attain it which only fuels their sense of resentment towards a “rotten” society.

The unnamed protagonist (Ren Nagase) has come to Tokyo from Kobe to attend university and as his family are not wealthy is supposed to be studying for a scholarship exam while supporting himself with part-time jobs. Only as he’s abruptly let go from his side gig, he finds himself unfulfilled by his studies and wondering what the point is in wasting his youth just to lead a dull life of drudgery. In an intense act of self-sabotage which later goes viral, he tells his English professor (Makiko Watanabe) to her face that her classes are pointless while calculating exactly how much they cost per hour which turns out to be the equivalent to three hours of labour for his mother, the price of a new text book, or three months’ Netflix subscription which oddly becomes a kind of currency benchmark. He can’t see that anything he’s learning will be of much use to him in the further course of his life when the only prize is conventionality even if that conventionality might also provide basic comfort.

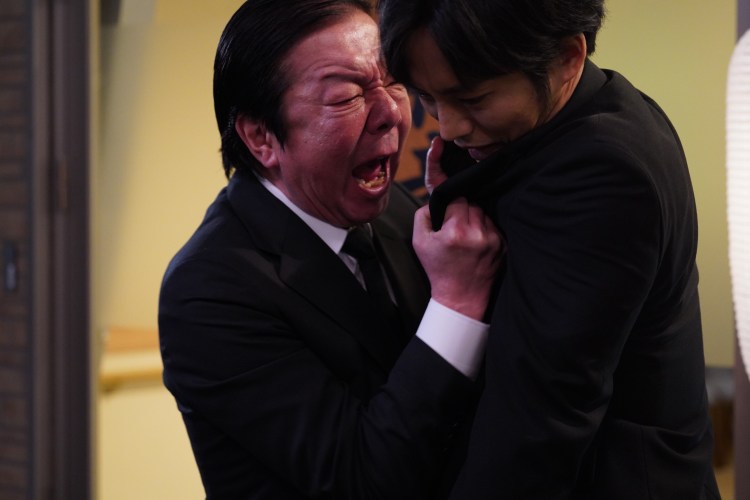

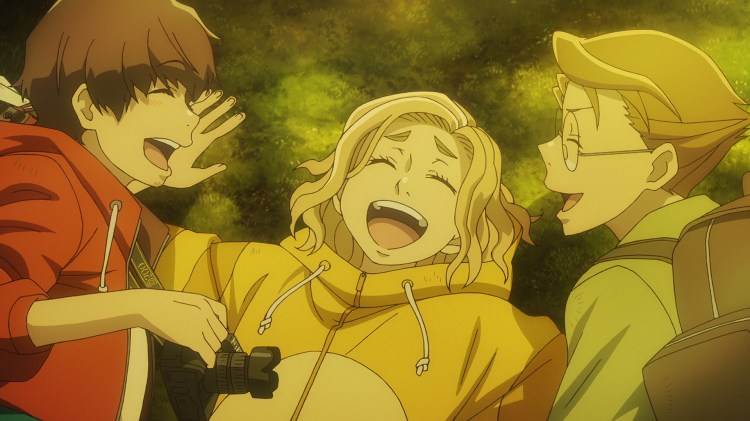

After joining a mysterious “hide and seek” club and becoming distracted by a series of minor bombings of public bins on campus, the hero is pulled between a woman only known as “Sempai” (Elaiza Ikeda), and a man only known as “The Man in the Black Suit” (Tasuku Emoto) who sell him conflicting visions of hope and darkness. While Sempai thinks it’s wrong to belittle those who want to live their lives and are genuinely content with the conventional, The Man in the Black Suit quite literally wants to burn it all to the ground. What begins as an awkward friendship between two awkward men, soon develops into a cult-like organisation of, as the hero puts it, “social outcasts”, drawn to the Man in the Black Suit’s desire to destroy the rotten society which has rejected them through blowing up Tokyo on Christmas Day.

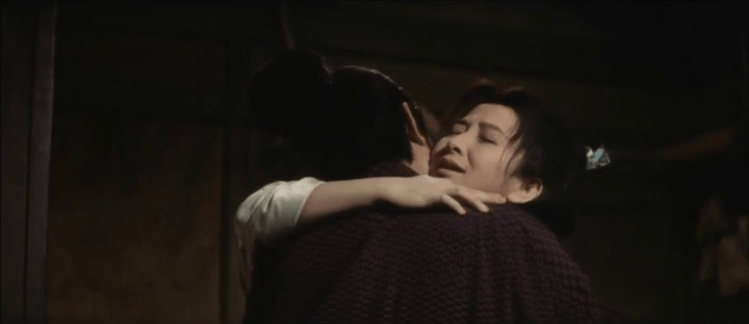

Positing Tokyo Tower as the “root of unhappiness”, the hero claims he wants only to destroy, and most particularly himself along with everything else. Experiencing extreme ennui, he struggles to find meaning in his life yet is also conflicted in the breadth of the The Man in Black’s goals being fairly indifferent to the existence of others and unconvinced that those merely complicit in the system should also be targets of his social revenge. If not quite dragged towards the light, he realises that he must kill the nihilist within himself and in a sense be reborn, as the Man in Black puts it, as the god of a new world. “You’re alive, that’s good enough for me” Sempai echoes as the hero does at least in a sense embrace life even amid so much destruction.

Ken Ninomiya has become closely identified with a singular style heavily inspired by music video and often taking place in Tokyo clubland. Midnight Maiden War is in many ways a much more conventional film mimicking the aesthetic of other similarly themed manga and light novel adaptations featuring only one real party scene and no extended musical sequences while routing itself in a more recognisably ordinary reality albeit one secretly ruled by a lonely tech genius. It does however feature his characteristic neon-leaning colour palate, focus pulls, and striking composition such as the revolving upside down shot which opens the film and hints at the unnamed protagonist’s sense of dislocation. Quite literally a tale of darkness and light, the film finds its dejected hero struggling to find meaning in a stultifying existence but perhaps finally discovering what it is to live if only at the end of the world.

The Midnight Maiden War screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Original trailer (English subtitles)