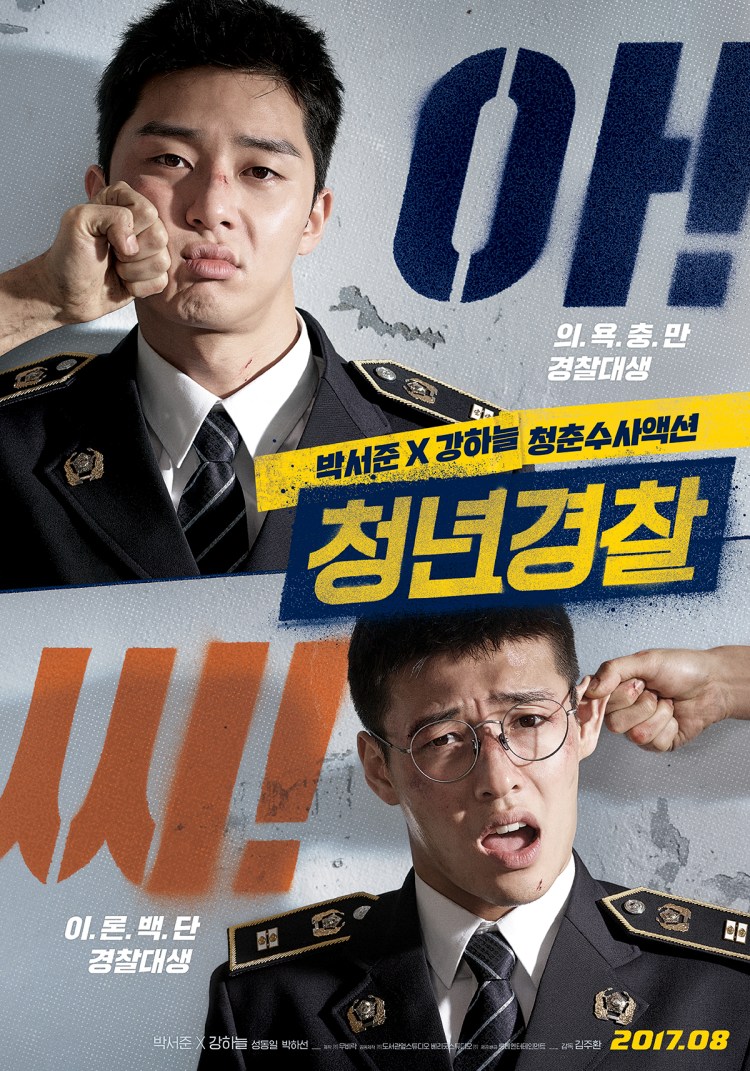

There are many good reasons for applying to Police University, even if many people can’t see them. That aside, the heroes of Kim Joo-hwan’s Midnight Runners (청년경찰, Chungnyeongyungchal) have ended up there not through any particular love of honour and justice, but simply because it was cheap, on the one hand, and because it was different, on the other. An ‘80s-style buddy (not quite) cop comedy, Kim’s followup to the indie leaning Koala is the story of two young men finding their calling once their latent heroism is sparked by witnessing injustice first hand, but it’s also careful to temper its otherwise crowd pleasing narrative of two rookies taking on evil human trafficking gangsters with a dose of background realism.

There are many good reasons for applying to Police University, even if many people can’t see them. That aside, the heroes of Kim Joo-hwan’s Midnight Runners (청년경찰, Chungnyeongyungchal) have ended up there not through any particular love of honour and justice, but simply because it was cheap, on the one hand, and because it was different, on the other. An ‘80s-style buddy (not quite) cop comedy, Kim’s followup to the indie leaning Koala is the story of two young men finding their calling once their latent heroism is sparked by witnessing injustice first hand, but it’s also careful to temper its otherwise crowd pleasing narrative of two rookies taking on evil human trafficking gangsters with a dose of background realism.

Rookie recruits to Seoul’s Police University, Gi-jun (Park Seo-joon) and Hee-yeol (Kang Ha-neul) could not be more different. Gi-jun is exasperated by his worried mother’s words of parting, but hugs her goodbye anyway. Hee-yeol’s dad looks on in envy at this touching scene, but asking if he should hug his son too gets a resounding “no” before Hee-yeol begins to walk away, turning back to remind his father to button his coat because it’s cold outside. Gi-jun doesn’t want to get his hair cut because he’s fashion conscious, whereas Hee-yeol doesn’t want his cut because they don’t sterilise the clippers and he doesn’t want to catch a bacterial skin infection. Nevertheless, the pair eventually bond first during lunch as Hee-yeol surrenders his “carcinogenic” sausages to the always hungry Gi-jun, and then when Hee-yeol sprains his ankle during the final endurance test and Gi-jun (eventually) agrees to carry him to the finish line. Not for the first time, Gi-jun’s “selfless” actions to help a person in need earn the pair a few words of praise from their commander who berates the others for running past an injured comrade and thinking only of themselves when the very point of a police officer is to help those in need.

A year a later the pair are firm friends and decide to take a night on the town to find themselves some girlfriends to spend Christmas with. Sadly, they do not find any but they do find crime when they spot a pretty girl in the street and then spend ages arguing about asking for her number only to see her being clubbed over the head and bundled into a black van. Slightly drunk, the boys panic, chase the van, and ring the police but are told to stay put and wait for a patrol car. They figure they can get to the police station faster than a car can get to them but once they do they realise the entire station is being pulled away on another high profile case and no one’s coming. They do what it is they’ve been trained to do, investigate – but what they discover is much darker than anything they’d imagined.

Police in Korean cinema often have a bad rap. It’s nigh on impossible to think of any examples of heroic police officers who both start and finish as unblemished upholders of justice. Midnight Runners, however, attempts to paint a rosier picture of the police force, prompting some to describe it almost as a propagandistic recruiting tool. It helps that Gi-jun and Hee-yeol are still students which means that the idealistic line they’re being fed goes mostly unchallenged (at least until the climactic events prompt them to think again), but there are certainly no beatings, no shady dealings with the underworld, or compromised loyalties in the boys’ innocent quest to rescue a damsel in distress.

The spectre of corruption hovers in the background but on a national, rather than personal, level as the news constantly reports on the kidnapping of a wealthy CEO’s child while a young woman from a troubled background has also gone missing but no one, not even the police who have devoted all their resources to the CEO’s case, is interested. Meanwhile, Gi-jun and Hee-yeol, having just escaped from certain death, attempt to get help from a nearby police box but the shocked jobsworth of a duty officer won’t help them because they don’t have their IDs. The boys’ outrage on being informed that despite all their efforts, the specialist team who handle cases like these won’t even be able to look at it for weeks is instantly understandable, but so is their professor’s kindly rationale that all lives are equal and the squad can’t be expected to dump their current caseload and swap one set of victims for another. The police, so it goes, are heroes caged by increasing bureaucracy which has made them forget the reasons they became policemen in the first place.

Despite the grim turn the film takes after Gi-jun and Hee-yeol make a shocking discovery as a result of their investigation, Kim keeps things light thanks the boys’ easy, symbiotic relationship filled with private jokes and even a cute secret handshake. Jokey slapstick eventually gives way to hard-hitting action as the rookie officers finally get to try out some of their training and find it effective on entry level street punks, but less so on seasoned brawlers with mean looks in their eyes. Told to “leave things to the grown ups”, Gi-jun and Hee-yeol decide there are things which must be done even it is dangerous and irresponsible because no one else is going to do them (whether that be eating sausages or rescuing young women no one else seems to care about). A strange yet fitting place to make the case for a better, less selfish world, Midnight Runners is a buddy cop throwback which brings the best of the genre’s capacity for humour and action right back with it.

Currently on limited release in UK cinemas.

Original trailer (English subtitles – select from menu)

A samurai’s soul in his sword, so they say. What is a samurai once he’s been reduced to selling the symbol of his status? According to Scabbard Samurai (さや侍, Sayazamurai) not much of anything at all, yet perhaps there’s another way of defining yourself in keeping with the established code even when robbed of your equipment. Hitoshi Matsumoto, one of Japan’s best known comedians, made a name for himself with the surreal comedies Big Man Japan and

A samurai’s soul in his sword, so they say. What is a samurai once he’s been reduced to selling the symbol of his status? According to Scabbard Samurai (さや侍, Sayazamurai) not much of anything at all, yet perhaps there’s another way of defining yourself in keeping with the established code even when robbed of your equipment. Hitoshi Matsumoto, one of Japan’s best known comedians, made a name for himself with the surreal comedies Big Man Japan and

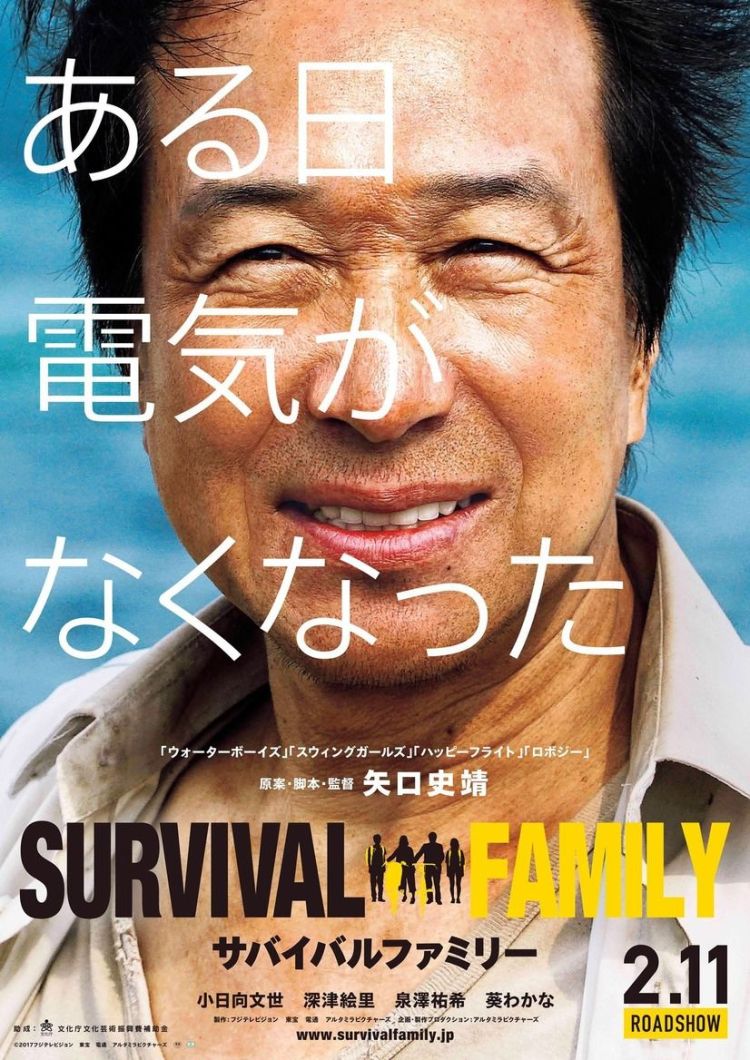

Modern life is full of conveniences, but perhaps they come at a price. Shinobu Yaguchi has made something of a career out of showing the various ways nice people can come together to overcome their problems, but as the problem in Survival Family (サバイバルファミリー) is post-apocalyptic dystopia, being nice might not be the best way to solve it. Nevertheless, the Suzukis can’t help trying as they deal with the cracks already present in their relationships whilst trying to figure out a way to survive in the new, post-electric world.

Modern life is full of conveniences, but perhaps they come at a price. Shinobu Yaguchi has made something of a career out of showing the various ways nice people can come together to overcome their problems, but as the problem in Survival Family (サバイバルファミリー) is post-apocalyptic dystopia, being nice might not be the best way to solve it. Nevertheless, the Suzukis can’t help trying as they deal with the cracks already present in their relationships whilst trying to figure out a way to survive in the new, post-electric world. Japanese cinema has its fare share of ghosts. From Ugetsu to Ringu, scorned women have emerged from wells and creepy, fog hidden mansions bearing grudges since time immemorial but departed spirits have generally had very little positive to offer in their post-mortal lives. Twilight: Saga in Sasara (トワイライト ささらさや, Twilight Sasara Saya) is an oddity in more ways than one – firstly in its recently deceased narrator’s comic approach to his sad life story, and secondly in its partial rejection of the tearjerking melodrama usually common to its genre.

Japanese cinema has its fare share of ghosts. From Ugetsu to Ringu, scorned women have emerged from wells and creepy, fog hidden mansions bearing grudges since time immemorial but departed spirits have generally had very little positive to offer in their post-mortal lives. Twilight: Saga in Sasara (トワイライト ささらさや, Twilight Sasara Saya) is an oddity in more ways than one – firstly in its recently deceased narrator’s comic approach to his sad life story, and secondly in its partial rejection of the tearjerking melodrama usually common to its genre. There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country.

There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country. Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes.

Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes. Kenji Uchida travelled to America’s San Fransisco State University to study filmmaking before returning to Japan and making this, his debut film, Weekend Blues (ウィーク エンド ブルース) which later went on to claim two awards at the prestigious Pia Film Festival for independent films earning him the scholarship which enabled his next film,

Kenji Uchida travelled to America’s San Fransisco State University to study filmmaking before returning to Japan and making this, his debut film, Weekend Blues (ウィーク エンド ブルース) which later went on to claim two awards at the prestigious Pia Film Festival for independent films earning him the scholarship which enabled his next film,  John Woo is best known in the West for his “heroic bloodshed” movies from the ‘80s in which melancholy tough guys shoot bullets at each other in beautiful ways. However, he had a long and varied career even before which began with Shaw Brothers and a stint in traditional martial arts movies. What often gets over looked outside of Woo’s native Hong Kong is his many comedies, of which The Pilferer’s Progress (AKA Money Crazy, 发钱寒, Fa Qian Han) is one of his most successful.

John Woo is best known in the West for his “heroic bloodshed” movies from the ‘80s in which melancholy tough guys shoot bullets at each other in beautiful ways. However, he had a long and varied career even before which began with Shaw Brothers and a stint in traditional martial arts movies. What often gets over looked outside of Woo’s native Hong Kong is his many comedies, of which The Pilferer’s Progress (AKA Money Crazy, 发钱寒, Fa Qian Han) is one of his most successful. Kihachi Okamoto might be most often remembered for his samurai pictures including the landmark Sword of Doom but he had a long and extremely varied career which saw him tackle just about every conceivable genre and each from his own characteristically off-centre vantage point. The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman (江分利満氏の優雅な生活, Eburi Man-shi no Yugana Seikatsu) sees him step into the world of the salaryman comedy as his hapless office worker reaches a dull middle age filled with drinking and regret imbued with good humour.

Kihachi Okamoto might be most often remembered for his samurai pictures including the landmark Sword of Doom but he had a long and extremely varied career which saw him tackle just about every conceivable genre and each from his own characteristically off-centre vantage point. The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman (江分利満氏の優雅な生活, Eburi Man-shi no Yugana Seikatsu) sees him step into the world of the salaryman comedy as his hapless office worker reaches a dull middle age filled with drinking and regret imbued with good humour. If there’s one thing you can say about the work of Japan’s great comedy master Koki Mitani, it’s that he knows his cinema. Nowhere is the abundant love of classic cinema tropes more apparent than in 2008’s The Magic Hour (ザ・マジックアワー) which takes the form of an absurdist meta comedy mixing everything from American ‘20s gangster flicks to film noir and screwball comedy to create the ultimate homage to the golden age of the silver screen.

If there’s one thing you can say about the work of Japan’s great comedy master Koki Mitani, it’s that he knows his cinema. Nowhere is the abundant love of classic cinema tropes more apparent than in 2008’s The Magic Hour (ザ・マジックアワー) which takes the form of an absurdist meta comedy mixing everything from American ‘20s gangster flicks to film noir and screwball comedy to create the ultimate homage to the golden age of the silver screen.